When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Put Your Personal Brand into Action

Allen Slade

Personal brands are important for entrepreneurs, leaders and jobseekers. To maximize your impact, you need a personal brand statement like this:

For [a specific person or group], I want to be known for [six adjectives] so I can deliver [valuable outcomes].

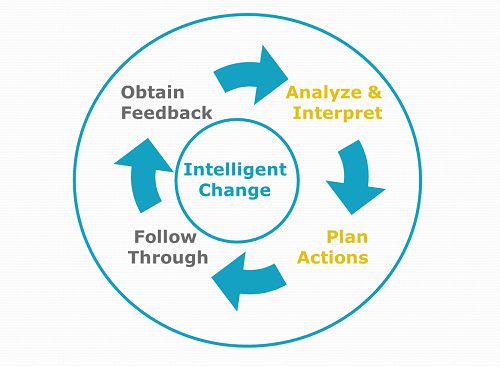

To make a difference, your brand has to move from words to action. You need to turn the wheel of intelligent change.

1. Take your personal brand statement and plan an action. For a jobseeker, you might revise your LinkedIn profile. For a leader, you might change a meeting format. For an entrepreneur, you might revise your company’s website. Whatever you do, ask “How can this profile/meeting/website/etc. project my personal brand better?”

2. Make the change on a small scale. Give it your best shot.

3. Get feedback. On the first turn of the wheel, ask someone in your circle of trusted advisors how they think the new approach reflects your personal brand.

4. Analyze and interpret the feedback. This is critical. To make intelligent change, you will not blindly do everything your advisor suggests.

Your next steps depend on the nature of the feedback.

Continue Forward Movement

Suppose your advisor likes what you have done? On the next turn of the intelligent change wheel, use the positive feedback to move ahead:

Keep going. Do more change in the same direction. If your change was tightening up your resume, cut more factoids that don’t support your brand. If your meeting approach was to generate more empowerment and participation, give up even more control over the agenda. If your website redesign involved a powerful brand message, add graphics to reinforce the message.

Go public. Test your idea beyond your circle of trusted advisors. Put your LinkedIn profile online, hold the meeting with your new approach or launch your website.

Switch topics. After you get this part of your brand close enough, switch to another arena. As a jobseeker, you might work on interview responses to reflect your personal brand. As a leader, you work on one-to-one communication to drive empowerment. As an entrepreneur, you might develop your elevator conversation. Whatever you work on, use your brand statement to plan your action, take action, get feedback and think hard about how well you are projecting your brand image.

Whatever you do next, plan it carefully before taking action. Then, get more feedback to get ready for the next turn of the wheel.

Get Unstuck

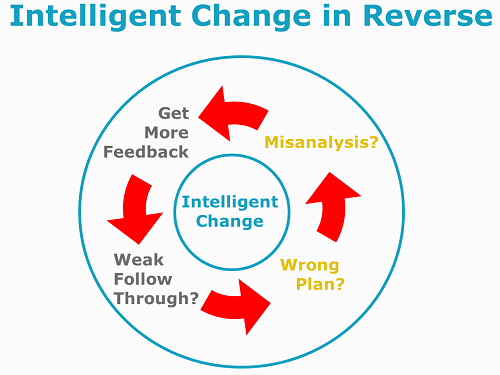

If you receive mostly negative feedback, what should you do? Like a car stuck in the snow, consider using reverse. Go backwards through the intelligent change wheel to figure what you can do to get unstuck.

Was your follow through weak? You had a great plan for a great brand, but you got sloppy on implementation. Polish your implementation and get more feedback.

Was your plan off target? Maybe the problems is with the action you took. Maybe your brand statement is off – your six adjectives may not create a desirable image, your outcomes may not be valued by your target group or, most troubling, you may not be credible enough to pull it off. Revise your planned action or revise your brand, follow through and get more feedback.

Have you misinterpreted the feedback? It is possible that the feedback you received was off base. In my experience, if you ask someone for feedback on your resume, they almost always suggest changes. Their suggestions reflect their personal style. But, if one advisor suggests a chronological resume, the next advisor suggests a functional resume and the third advisor suggests an accomplishment based resume, you know they can’t all be on target. Be careful with discounting feedback, however. Generally, think hard about your follow through and your plan before you reject feedback.

Whether the feedback you receive on your brand action is positive, negative or a mix, continue to take action and get more feedback. I have been speaking about personal branding for years, yet I still continue to work on my brand. I will be done defining, articulating and delivering on my personal brand after someone gives my eulogy. I humbly suggest that you should do the same. Until then, continue to turn the wheel of intelligent change to polish your brand and deliver valuable outcomes to the people you serve.

Test Your Ejection Seat

Allen Slade

Felix Baumgartner’s space jump had a dramatic buildup to a truly amazing physical feat. The video of Baumgartner spinning and tumbling at 700 m.p.h. is heart wrenching. And it ended with a perfect landing.

However, the “mission” was presented as a NASA-like experiment to make space jumping viable for escaping from a space vehicle. The mission was not very NASA-like. The flight director was no Chris Craft. And Baumgartner is an extreme athlete, not an astronaut. His poor checklist discipline and his concern with styling his hair after removing his helmet was more Tom Cruise than Alan Shepherd.

My father, Harry Slade, worked at NACA/NASA from the beginning of the jet age through the space shuttle. And, in 1976, in the New Mexico desert, he helped test one of the oddest emergency systems in the world: a helicopter ejection seat. How does Baumgartner’s space jump compare to a helicopter ejection seat?

The best ejection seats are virtually automatic – pull one lever and hang on. Baumgartner’s exit was slow and difficult: a long checklist and keeping his cool while tumbling at 700 m.p.h. But Baumgartner did not jump from a hypersonic spacecraft. He bunny hopped from a capsule floating gently beneath a balloon.

Space jumping will require more planning and testing before it provides real safety. In an emergency space jump, the craft would probably be spinning, disintegrating or on fire. A Baumgartner-like jump would be too complex and too physically stressful for a space tourist to survive.

NASA’s helicopter ejection seat was not like the space jump. The ejection seat was for a helicopter testing next generation rotor blades. Test rotors were thinner and lighter, increasing the risk of failure. Rotors are most likely to fail during takeoff and landing. A pilot could not eject down because of the low altitude. The pilot cold not eject sideways either, because rotor debris would be spiraling to every point of the compass. The ejection seat had to go up, through the path of the rotors. The ejection sequence was complex: pull the ejection handle, blow off the rotors with explosive bolts, blow the hatch, eject the seat, cut the seatbelts, then deploy the parachute. Asking a pilot to remember these steps during a crash was a recipe for failure. The pilot’s only job was to pull the ejection handle and let the automatic system do the rest.

For leaders, when the crisis happens, it is usually too late to build an ejection seat. When time and tempers are short, people go into survival mode. The brain shuts down cognitive processes, attention narrows and choices seem limited to fight or flight. What backup plans do you need to create? Your leadership crisis may be the loss of a key employee, an unexpected customer request, failure of essential equipment or overload of a critical operation. If the crisis happens quickly, you need to already have an ejection seat.

For a job interview in 2002, I made a presentation on leadership. I emailed my presentation to the host. By plan, I arrived 15 minutes early to check the room. When we turned everything on, my presentation was not on the laptop and my host did not know how to transfer the file. (It was 2002.) No problem – I had a floppy disk. (No USB in 2002.) She found an external disk drive, but the drive did not work. No problem – I had transparencies. They found a dusty overhead projector. When we turned it on, the bulb did not work. No problem – I activated the built in back up bulb. The second bulb worked. I tested the projected image, focused the projector, focused my emotions and was ready to go. (I had one more backup if the second bulb blew – use the whiteboard.) The presentation went well, and I was offered the job.

Lesson #1: For critical activities, have multiple backup plans before the crisis.

The helicopter ejection seat offers another lesson. My dad was in New Mexico to test the seat. The helicopter was bolted to a jet sled, accelerated to flight speed, then a test dummy was ejected. The first test was almost right. The rotors did not blow off before the seat was ejected, shredding the test dummy. (A watching test pilot walked away saying “I’m never flying that bird.”) The NASA team found and fixed the flaw in the timing circuits. All the other tests were successful.

When I joined Microsoft in 1999, my key task was to make the employee opinion survey a success. The 1998 survey locked up because of overloaded servers at the survey host. Under my direction, we created backup plans for every problem we could imagine. More importantly, we tested our back up plans. We did load testing, usability testing, data integrity testing and translation testing. We even tested our testing. In effect, we accelerated the survey to flight speed and pulled the ejection handle. The testing identified problems that we fixed, then we tested to the point of repeated perfection. The actual survey went well – on time, with virtually 100% uptime.

Lesson #2: For critical activities, test your backup plans before the crisis. Make the tests as realistic as possible. And test your tests.

As a leader, what are your key processes? How can they fail? What are your plans for overcoming failure? And how well tested are those plans?

Don’t rely on extreme leadership ability in a crisis. Few of us can tumble at supersonic speed like Felix Baumgartner. Plan for failure and test your plans until you know your ejection seat will save the day.

Are You Just Showing Up?

Allen Slade

You probably had at least one meeting today. Why were you in that meeting? Woody Allen said “90% of life is just showing up.” He’s wrong. Leaders go to meetings to make a difference.

A meeting is like a journey:

You can focus on your next step, looking to avoid a misstep. This short range focus may help you avoid gaffes, but you won’t make much of a difference.

You can think about the next mile – how will we reach our goal for today? With a medium range focus, you can help make today’s meeting a success.

Or you can look to the horizon, and think about where you want to be in the future. With a long range focus, you are looking ahead to future meetings, future decisions and future leadership opportunities. You treat each meeting as an opportunity to grow your influence.

The best leaders do not choose between short, medium and long range focus in a meeting – they do all three at once. They craft a great comment while avoiding gaffes, they make today’s meeting a success and they develop their leadership, all at the same time.

Let’s focus on the long range impact of your meeting participation. As a leader, you should be mindful of your leadership presence in meetings. Do you appear timid? If so, you may not be seen as a leader. Do you talk too much? You may undermine your standing as an empowering leader or an effective team player. Let me suggest three ways you can be mindful of your meeting behavior.

1. If you want to manage your leadership presence in meetings, try noticing how much airtime you take up in meetings.

Airtime is the percent of time you are the focus of the team’s attention (talking, writing on the board, etc.). For a five person team with equal attention, each person should be the focus of attention about a fifth of the time – 20% airtime. A person dominating the conversation has 50% or more airtime.

It is rare that each person gets exactly the same airtime in a meeting. You may have more airtime because your expertise or passion fits the topic.

The point is not to set a specific percentage target. Just notice your airtime.

“Noticing airtime” is not a smart goal. It is not specific, measurable, actionable or time-bound. I am a big fan of smart goals as a powerful source of change, but they are not the only way to develop your leadership. Sometimes just noticing something – being mindful – is all that is needed to trigger a major behavioral change.

2. If the airtime goal doesn’t lead to the change you want, try the rule of three: “I will make 3 valuable contributions in every meeting.” For this to work, you need to do your homework. Study the agenda, do some research, collect some reports and prepare to make a difference.

3. For maximum impact, create a SMART goal. Decide on a plan for your participation in each meeting that is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. For example, “In next Monday’s meeting, I will comment on the product quality topic on the agenda. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story. I will practice using both the data and the story with my coach before the meeting. I will use the data, the story or both in the meeting.”

See each meeting as a leadership development opportunity. Stay focused to make a difference. Avoid missteps, push the decision ahead and grow your leadership all at the same time.

Holding a Difficult Conversation

Allen Slade

You are gearing up for that difficult conversation. It may be about a broken commitment, setting a boundary to halt abusive behavior or feedback that is unexpected and unwanted. You want to navigate the emotional minefield to minimize the chance of a catastrophic explosion.

Now what? How do you plan the difficult conversation for maximum gain and minimum risk?

Start with the end. In a previous post, I recommended planning your difficult conversation by starting with the end. Have a clear definition of success. Be sure the potential reward of the difficult conversation is worth the cost.

Don’t procrastinate. Bad news is like bread. It is best fresh. After a few weeks you don’t want it in the house. If you need to have a difficult conversation, do it sooner rather than later. If you need time to think and plan or if you want to check your plan with a coach or mentor, fine. But think of waiting hours or days, not weeks or months.

Begin well. Plan your opening statement. Make it appropriately assertive, following this pattern: When you [specific behavior, attitude or thinking pattern], it makes me [specific negative outcome.] Here are some examples:

“When you roll your eyes while we talk, I feel disrespected.”

“When we discuss customer complaints, you tend to blame other employees. This makes me think you don’t see a need for change.”

Listen more and talk less. Be curious about the other person’s reaction. Look to discover why they act/feel/think like they do. Don’t argue. Don’t project an attitude of certainty. Practice active listening by reflecting back what they say and asking lots of clarifying questions.

Anticipate their reaction. At a basic level, put yourself in their shoes. If you were on the receiving end of this difficult conversation how would you react? Even better, figure out the other person’s general pattern of responding to feedback. Do they have a problem with feedback or are they generally open to feedback? Then, prepare for their reaction. Control your emotions, listen without agreeing and keep the conversation moving ahead to address the issues.

Seek mutual problem solving and commitment. The goal of a difficult conversation should be intelligent change. To change, you need to work with the other person, first to figure out how to change and then to get a commitment to change. You should aim for a smart request, a specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound proposal that the other person accepts.

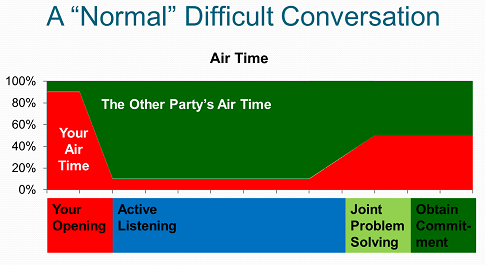

When you are at your best as a leader, your difficult conversation should follow this pattern.

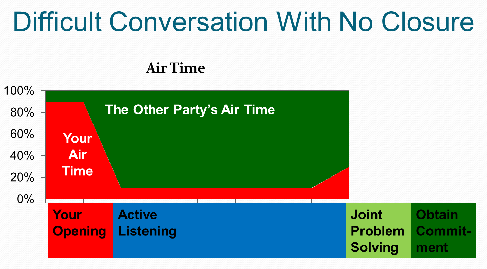

You will give most of the airtime to the other person. Only during your brief opening will you do most of the talking. The longest part of the conversation is your active listening, where you may do 10% of the talking or less. When you get to joint problem solving and mutual commitment, you should look to do 50% or less of the talking.

Let’s be realistic. Some difficult conversations do not end with a solution. The other person may be too stubborn. If you do your part well, but the other person resists your efforts, your difficult conversation may turn out like this.  This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

I had a difficult conversation with an intern that started: “Dolly, your work has been slipping recently. Several people have reported smelling alcohol on your breath. I am concerned about your reputation. I am reluctant to assign you to important projects or have you go to meetings without me.” Dolly never admitted to a drinking problem. She did not agree to seek help. Yet, the issue disappeared overnight. When her internship ended months later, I gave her high performance ratings and a stellar recommendation.

If the other person has difficulty admitting a personal failing, there can still be change, but it will follow a different pattern. The individual you confront may go back to their office and think about what you said. Sometimes, that triggers the change you seek. They may never admit you were right or confess their shortcoming. That’s OK. You can live with the change even if you don’t get the apology.

The worst case is that change does not happen. Let’s acknowledge that we are dealing with adults. You can’t make the other person bend to your will. Give it your best shot – hold the most effective difficult conversation you can – but accept that they must decide whether to address your concerns. If they do not change, you can make other moves. You can set boundaries, end the relationship or get others involved in resolving the situation. Your key responsibility is to have the best difficult conversation you can without pretending you can control the other person’s reaction.

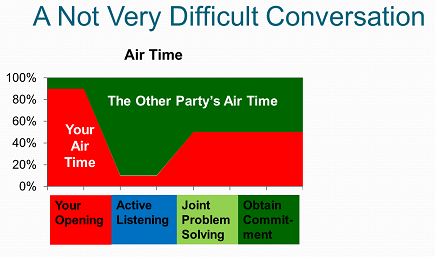

I have coached many clients on how to hold a difficult conversation. We work together to craft a powerful opening. We practice listening. We practice managing emotions. We even role play the difficult conversation. And then, my client goes off to hold the conversation. Surprisingly often, my client is surprised because the conversation turns out to be not very difficult at all.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

My thanks to executive coach Art Gingold for refining my thinking on difficult conversations.

Getting to the Center of an Emotional Storm

Allen Slade

The oddest thing about hurricanes is the calm at the center of the storm. Pelting rain and destructive winds depart. The wind is calm and the sun is shining. You know the eye won’t last, but you can take a break, step outside, do a quick check and plan how to face the rest of the storm.

Sometimes our emotions swirl like a storm. Today’s post focuses on how leaders can calm their emotions through centering. This is step four of managing emotions:

- “How am I feeling?”

- “How are my emotions serving me right now?”

- “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?”

- “How do I get there?”

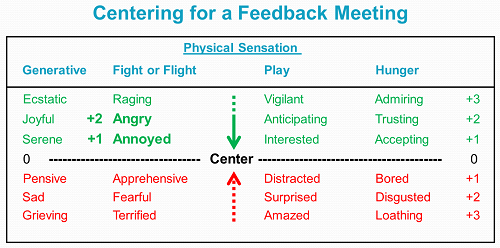

For example, in a feedback meeting with a difficult employee, your fight sensation might be activated. You and your employee would be better served if you have less intense emotions. On the emotional scale below, you don’t want be so intense that you are angry (+2). However, annoyed (+1) would serve you well.

If you decide your emotions are too intense, then how can you move closer to the center? How can you create an eye in an emotional storm?

You can create emotional calm with centering. By focusing your thoughts and calming your body, you can reduce the intensity of your emotions. I use a centering exercise with my clients that takes about five minutes. It can lower your heart rate, reduce your blood pressure and (most importantly) reduce the intensity of your emotions.

You center to reduce your emotional intensity, not to totally bury your emotions. In that feedback meeting with your difficult employee, being completely serene won’t work. You care about performance and you expect to see a change. You want to experience annoyance rather than anger or rage. In general, at work we want emotional intensity of -1 to 1. Emotions at intensity level 2 could be career limiting, except at farewell parties and new product launches.

What if you are in the middle of a meeting when your emotions kick in? It is not possible to close your eyes for five minutes, so you need other tactics to center your emotions.

If someone else is talking, you can center in your chair, Modify your full-length centering exercise so it is shorter. Then, mentally check out of the meeting for 30-60 seconds. Staying seated with your eyes open, run through your routine. Here is one way to center in your chair.

If you are in the spotlight – it is your speech or you have just been called on – you can’t leave for five minutes or check out for 30 seconds. Then, your best move can be to center in the moment by taking a deep breath, touching your touchstone or making a silent declaration.

Breathing. All three exercises – centering, centering in your chair and centering in the moment – involve breathing. Taking a deep, controlled breath oxygenates your blood. This helps lower your pulse, blood pressure and adrenaline. It also establishes, at a visceral level, that you are in control. If one breath doesn’t center you enough, do two more.

Touchstone. A touchstone or totem is something you carry with you to remind you of your purpose and passion. It should have some personal meaning to you. I touch my signet ring. My ring has a custom symbol that reminds me of the important areas of my life – faith, family, friends and work. When I touch it, I remember who I am and what I am about. Your touchstone could be a piece of jewelry, a small stone, or any item that is convenient. The key is that your touchstone should be meaningful to you and should be on you whenever you might face an emotional storm.

Declaration. A centering declaration is a brief, silent statement about your purpose and identity in the form of “I am …” or “I will …” The nature of declarations will be the topic of my next post.

Managing your emotions puts you in charge. You identify your feelings and then deliberately moderate your feelings to serve you and the people around you. Even when your situation is emotionally fraught, you can manage your emotions. You can find the calm you need in the midst of an emotional storm.