When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

What to Expect from Leadership Coaching

Allen Slade

Gifts can be a source of joy or a nasty surprise. If your company provides you a leadership coach, how should you react? Heartfelt delight or muted disappointment? Is leadership coaching the perfect gift for you? Or is it the ugly sweater?

Leadership coaching is a powerful gift when it works as designed. Coaching increases your ability to achieve results and build healthy relationships. It helps you stretch into your best self as a leader.

A talented and wise coach (preferably accredited) will help you stretch into your best self. The coaching conversation can be the high point of your week. Your coach’s insightful listening and powerful questions can trigger new insights into your leadership. The best coaches assume that you are the expert on your own situation. Your coach will draw out your expertise through inquiry, curiosity and gentle challenges. The mini-experiments you design together can lead to breakthroughs in your influence and your presence as a leader.

Leadership coaching comes in different flavors:

Coaching for achievement maximizes your performance in your current role. The leader wants to move from good to great. Your leadership coach will help you focus on the behaviors and thinking necessary to supercharge performance. For achievement coaching to have maximum value, you need to have already learned the ropes. That means 6 months or more in your current job.

Coaching in transition helps you adjust to a new role so you can have a fast start. Your coach will help you learn the ropes – making sense of your new role. Rapid sense-making will help you adjust your behavior, thinking and expectations to accelerate maximum performance in your new role. Transition coaching may start before, during, or soon after the leader has moved into a new role. Sometimes, recruiting firms will provide a leadership coach to ensure that the placement has the greatest odds of success.

Coaching in crisis is designed to turn around an unsuccessful situation. The leader’s performance is unacceptable in one or more ways, and the leader and the organization want to improve the situation. Successful crisis coaching requires the leader, HR and the leader’s manager to agree to have mutual candor, commitment to change and the expectation that things can improve.

When can the gift of coaching turn out to be an ugly sweater? One example is coaching in crisis when the organization has already decided to end the leader’s employment. Another example is when the leader’s confidentiality is violated.

Most ICF accredited coaches take steps to avoid these situations. If no turnaround is possible, Slade & Associates does not offer coaching in crisis. (However, if the leader’s employment is at an end, we gladly offer career coaching as part of outplacement packages.) We always require a written agreement of strict confidentiality. Our approach to leadership coaching safeguards our dialogue, maximizes your insight and drives intelligent change for your organization.

Leadership coaching is an incredible benefit. If your organization offers you a leadership coach, accept the gift gladly. Check on the coach’s credentials. Make sure your coach, your organization and you agree on the purpose of the coaching. Demand coaching confidentiality. Then, prepare to be surprised and delighted as you unwrap the insights and wisdom of leadership coaching.

Feedback Should be “Just Right”

Allen Slade

A careful reading of Goldilocks and the Three Bears suggests three lessons for leaders: Moderation in all things. Don’t be impulsive. Breaking & entering causes problems, especially at the Bears.

Previous posts have looked at The Problem with Feedback and Different Perspectives on Feedback. Today, we will consider moderation in two aspects of feedback. Instead of a single feedback cycle that may be too hot or too cold, just right feedback requires that you mix the timing of your feedback cycles. And, don’t just impulsively act on feedback. Use insight and analysis to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose.

Multiple Feedback Cycles

As a leader, you should be open to feedback because you need to know “When I walk in the room, who shows up for the other people?” You need to seek out feedback relentlessly.

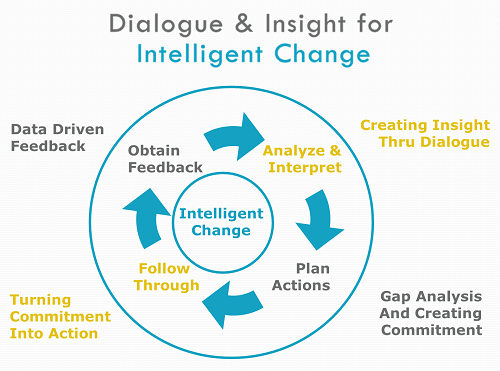

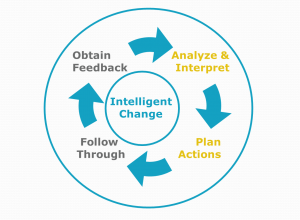

But it is not enough to collect feedback tidbits. To drive intelligent change, you must analyze and interpret the feedback you receive. You must plan actions based on the feedback. You must follow through with your plans. Then, you must start the cycle again by collecting more feedback. If things are going well, continue on. If your feedback suggest things are not going well, change something – your follow through, your action plan or your analysis and interpretation of the feedback. This feedback cycle drives intelligent change.

How long should your cycle take? Consider feedback cycles of three lengths:

Long-cycle feedback. This is feedback on long term impact, such as data from the annual employee opinion survey or a 360 report. Long-cycle feedback looks at the sum of your actions over a period of time. Long-cycle feedback is typically generated by the organization with safeguards to increase its validity (e.g., anonymity) and relevance to organizational leadership (e.g., a competency model). Yet long-cycle feedback by itself is not enough to develop your leadership. The assessments underlying long cycle feedback are complex and open to rating errors. And, a leader cannot afford to wait a year to find out if leadership changes are effective.

Short-cycle feedback. This is feedback on a recent event, such as post action feedback right after a meeting. Short-cycle feedback looks at your actions in the very recent past. The advantage of short-cycle feedback is that it reduces the delay in adjusting a new behavior. The disadvantages of short-cycle feedback are often a lack of anonymity and a lack of structure.

The quick check-in is a useful form of short-cycle feedback. After a conversation or meeting, ask “How did today’s conversation (or meeting) go for you?” Most of the time, the answer will be “It went well.“ or ”Great.” In that case, continue on. Sometimes, you will hear something of incredible value. “We are bogging down in the data.” “To be honest, I was bored.” “You have spinach between your teeth.” Treat this feedback as a valuable nugget. Adjust the agenda, amp up the excitement or do a quick floss job.

Instant feedback. This is feedback in the moment, such as watching non-verbal language of others in a meeting or hearing a change in voice tone during a phone call. Instant feedback allows the leader to adjust on the fly. Instant feedback requires mindfulness of the cues that others give in the moment. It also requires the ability to multi-task by talking and watching, by focusing on your message and your impact on the other party, at the same time.

You need a mixture of these cycles. Instant feedback and short-cycle feedback, in excess, may be too hot. Long-cycle feedback, by itself may be too cold. But, combined in the right proportions, these different cycles can be just right.

Balancing Openness to Feedback with Constancy of Purpose

When you receive feedback, another form of moderation is needed. You need to consider the feedback before acting. In the heat of the moment, while receiving negative feedback, you can go overboard. You can impulsively agree to do everything the feedback giver wants. This strong desire to please can backfire. If you submit totally to the other person’s judgment, you undermine the powerful dialogue that should come with feedback. And, you subordinate your purpose to their goals for you. In effect, you jump from feedback to action plan without your own careful analysis and interpretation.

It is better to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose. The other person’s feedback is always valid and always valuable. Yet their goals for you may not be identical to your purpose. My advice is to accept all feedback from all willing parties, without necessarily submitting to their action plans for you. The balanced reaction to feedback is to listen, to learn and to engage the other person in mutual problem solving.

Back at the Bears

Let me close with another observation: Goldilocks had no support team for her decisions. Impulse can be moderated by wise counsel. Mixing feedback cycles is more complex than simply waiting for annual leadership feedback. Balancing openness to feedback with constancy of purpose is harder than a simple rule for action. I recommend using the power of collaboration to maximize the power of feedback. Work with your circle of trusted advisors, your mentor or your leadership coach to master feedback. Gather a support team to create dialogue and insight to drive intelligent change for your leadership.

Bottom line: As a leader, actively seek feedback. Gather the right mix of long-cycle, short-cycle and instant feedback. Balance constancy of purpose with openness to feedback. Gather your support team to get your use of feedback just right.

And don’t break & enter, especially at the Bears.

Different Perspectives on Feedback

Allen Slade

I see performance feedback sessions as an excuse for a great conversation. Not everyone shares my perspective. One manager at Microsoft gave performance feedback by Post-It note. The day of reviews, she got into work early and stuck a note on each monitor with a review score, merit pay, bonus and stock options. Then, she took the rest of the day off. I was aghast. In my mindset, this manager had great cowardice instead of a great conversation.

As a leader, have you been surprised at someone else’s approach to feedback? Suzanne Cook-Greuter lists seven ways to respond to feedback[1]:

Opportunist. Focuses on own immediate needs and opportunities. Values self-protection. Receives feedback as an attack or threat.

Diplomat. Focuses on socially expected behavior. Values approval of others. Sees feedback as disapproval or judgment.

Expert. Focuses on expertise, procedure and efficiency. Values expertise in self and others, but takes feedback personally as an attack on own expertise. Defends, denies, and delays feedback, especially from lesser experts.

Achiever. Focuses on delivery of results. Values effectiveness, goals and success. Accepts feedback if it helps achieve personal goals and improve effectiveness.

Individualist. Focuses on self interacting with the system. Individual purpose and passion are more important than the system. Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of their own behavior.

Strategist. Focuses on linking theory and practice. Looks for dynamic systems and complex interactions. Invites feedback for self-actualization.

Magician. Focuses on interplay of awareness, thought, action and effects. Values transforming self and others. Views feedback as natural and essential for learning and change.

Opportunists, diplomats and experts all have a problem with feedback. They resist negative feedback, breaking the cycle of intelligent change.

Today’s post focuses on achievers, individualists, strategists and magicians who all share an openness to feedback. Let’s look at each in detail:

4. The achiever wants to win – accomplish the goal, launch the product, land the contract. An achiever looks for a score, a time, or an amount; in other words, feedback that defines achievement. The achiever mindset seeks success within the status quo, like Zaleznik’s “manager.” The achiever plays the feedback game to win.

5. The individualist wants personal growth. Feedback is welcomed because it triggers growth and change. The individualist can return to the mindset of an achiever, going full speed after goals. But the individualist sees self-purpose as more important than the rules of the system. The individualist challenges the status quo, like Zaleznik’s “leader.” The individualist wants to fix the feedback game to make it better.

6/7. The strategist and the magician play the feedback game at a higher level. Instead of a single loop of feedback and action planning, strategists sees interconnected loops with multiple points of contact and causality. When I play Monopoly, I see math skills for my kids to develop, political dynamics for them to perceive and opportunities for them to make SMARTer requests. (At the same time, the individualist in me wants to grow as a parent and the achiever in me wants to win!) The magician sees feedback as integral to all healthy systems, so they create feedback loops, building systems on top of systems.

Bottom line: People think about feedback differently. Know yourself. Know how the people around you react to feedback. Adjust to maximize your influence.

Know yourself. As a leader, know your own mindset in accepting feedback. Which is your typical response to feedback? When you are at your best, what is your response? Your reaction to feedback depends in part on your mental and emotional state.

When I am caught off guard by negative feedback, I tend to react as an expert – defend, deny, and delay. If caught off guard, I try to say “This seems important. Can we talk about it tomorrow?” By delaying (instead of denying or defending), I can receive feedback when I am at my best. Know your triggers for ineffective responses to feedback and work around them.

Bridge to your employees. As a leader, you need to bridge between your mindset and the mindset of your employee. Bridging may involve translation, empathy and a mixture of resolve with patience.

Leaders often give performance feedback expecting the employee to react with an achiever’s mindset. The employee, with an expert mindset, sees the leader as a lesser expert with out-of-date skills and little sense of the actual job. The leader gives achievement-oriented feedback and the expert employee defends, denies or delays. The feedback meeting goes from bad to worse, because manager and employee both believe the other is naive, wrong or worse.

Translate your feedback into your employee’s mindset. In giving feedback to an expert, call on your expertise as a manager. “You know more about your job than me, but I know how management thinks.” If your employee is a diplomat, avoid judgmental words. “Let’s help you fly under the radar in the future.”

Be empathetic. Every mindset is built on all the earlier mindsets. If you are an achiever and your employee is an expert, regress a bit. Remember how to think as an expert and go from there.

Mix resolve and patience. Stick to your guns, but give your employee time to come around. Give continuous feedback so there are no surprises.

Bridge to your boss. As a leader, you and your boss may not share the same feedback mindset. If your boss is at an earlier feedback mindset than you, use translation, empathy, resolve and patience. If your boss is at a later feedback mindset than you, translation and empathy will be tougher because you don’t grasp their mindset yet. Be patient. Resolve to listen and learn so you can grow to think about feedback like they do.

People think differently about feedback. As a leader, bridge these differences with translation, empathy, resolve and patience.

The Problem with Feedback

Allen Slade

Most of us readily accept praise. But leaders can struggle with accepting and acting on constructive criticism. They can balk at negative feedback. Sometimes, it is reasonable to reject feedback because of its low credibility or irrelevance. However, habitually rejecting feedback suggests a deeper pattern – a world view that sees feedback as a problem.

Let’s get personal. How you respond to negative feedback?

Recall the last time you got substantial negative feedback on your work performance or professional relationships from your manager, colleague or close friend at work. How did you react?

1. I saw the feedback as an attack or threat.

2. I saw the feedback as disapproval or judgment.

3. I defended myself, denied the feedback was valid, or delayed receiving the feedback.

4. I accepted the feedback, even though I wanted to do well.

5. I welcomed the feedback.

6. I invited additional feedback.

Suzanne Cook-Greuter lists seven ways to respond to feedback[1]:

Opportunist. Focuses on own immediate needs and opportunities. Values self-protection. Receives feedback as an attack or threat.

Diplomat. Focuses on socially expected behavior. Values approval of others. Sees feedback as disapproval or judgment.

Expert. Focuses on expertise, procedure and efficiency. Values expertise in self and others, but takes feedback personally as an attack on own expertise. Defends, denies, and delays feedback, especially from lesser experts.

Achiever. Focuses on delivery of results. Values effectiveness, goals and success. Accepts feedback if it helps achieve personal goals and improve effectiveness.

Individualist. Focuses on self interacting with the system. Individual purpose and passion are more important than the system. Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of their own behavior.

Strategist. Focuses on linking theory and practice. Looks for dynamic systems and complex interactions. Invites feedback for self-actualization.

Magician. Focuses on interplay of awareness, thought, action and effects. Values transforming self and others. Views feedback as natural and essential for learning and change.

Today’s post focuses on opportunists, diplomats and experts – those who have response 1, 2 or 3 to negative feedback. Let’s look at each in more detail:

1. An opportunist lives for the moment, seeking passion with little long-term purpose. Since feedback is painful, the opportunist sees it as an attack or threat.

2. The diplomat wants to get along well with others. Feedback is disruptive. The diplomat prefers smoothing over differences.

3. Experts do not like feedback in their area of expertise, because it undermines their expertise. An expert will grudgingly accept feedback from a superior expert, but they often defend themselves by attacking the other person’s expertise.

Because of their problem with feedback, opportunists, diplomats and experts often struggle as leaders. In my experience, leaders must see themselves through the eyes of those they wish to lead. Cook-Greuter found that over 50% of adults have the mindset of an opportunist, diplomat or expert[2]. If half of us struggle in accepting feedback, is it any wonder that there is a shortage of effective leadership?

Bottom line: If you have a problem with feedback, you will struggle as a leader. Shift from seeing feedback as a problem to seeing feedback as a gift.

I am optimistic that anyone with a passion for leadership can develop the purpose necessary to accept feedback. Anyone who wants to help people can develop the norm that feedback is acceptable. Anyone who wants to be the best leader possible can become an expert in seeking and using feedback.

Changing your view of feedback is not easy. It requires substantial growth and development, possibly even a fundamental shift in your world view. Reflection, coaching and practice may help you open yourself to negative feedback. Reflection, such as a journaling, meditation or quiet time, can help you examine yourself and shape your impact as a leader. Leadership coaching helps you create a plan to improve your feedback skills and hold yourself accountable to put that plan in action. Like any other competence, practice accepting feedback is necessary. You need to find the right situations to practice receiving negative feedback. You may want to start in a safe and supportive environment, such as with your coach or in a training class. Then, practice with your trusted circle of advisors in your work situation. Soon, you will want to practice requesting feedback from a wider circle – including people whose expertise or motives are not always clear. Feedback from the bozos and politicians is a gift, because their perspective impacts your leadership as much or more than your circle of trusted advisors.

The problem with feedback is our unwillingness to receive negative feedback. The solution is simple but difficult: See feedback as a gift. If you solve the problem with feedback, if you tackle this simple but difficult change, you will become a better leader and lead a richer life.

[1] This table is adapted from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004) “Making the case for a developmental perspective,” Industrial and Commercial Training, 36, 275-281.

[2] Data from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004), p. 279.

The Leader’s Tipping Point

By Allen Slade

Leadership is about creating sustainable performance in your team. Jim Clawson points out that effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a post on The Tipping Point of Performance, I talked about managing energy in others to create sustainable performance. As a leader, you have a proven track record of results. You combine competence, capacity and committent to success, so people are willing to follow you. But is your performance sustainable?

Bottom line: As a leader, you have to manage your own energy. Know your performance curve, watch for signs of an impending performance crisis and take dramatic action as needed.

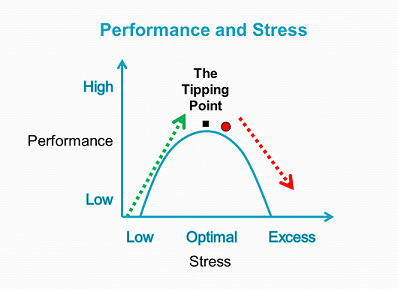

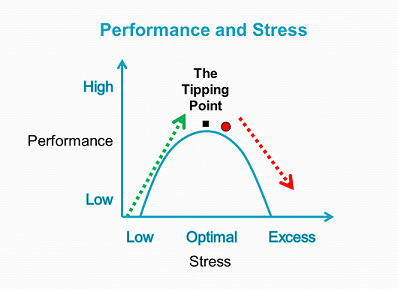

The performance curve is just as true for you as it is for the people you lead. We all experience this inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between your level of stress and your performance holds, but only in the green zone.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

Bottom line: Push youself, but know your own tipping point. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Manage your own stress wisely, especially on the dangerous part of the performance curve.

Stress reduction strategies. Whether you are at the top of the green zone or at the tipping point, try stress management strategies. Simplify your life. Practice centering. Off load non-essential work. Get help from your boss, in terms of more people, more resources or more time. Ask your colleagues for support. Delegate to your team.

Develop yourself. Long-term, grow your capacity for performance to avoid a stress-induced performance crisis. Develop new skills. Practice skills to the point of mastery. Practice for speed, not just completion. If you can write methodically, practice writing under a deadline. (Blogging three times a week is speeding up my writing!) Coaching can help, whether you are an executive, leader or golfer. At Slade & Associates, we coach executives and leaders to maximize their performance. There are certain things we don’t do, so you would do well to find your own golf coach.

Your urgency in reducing your stress depends on your position on the performance curve:

Top of the green zone. If you push harder but don’t see much improvement, you may be approaching the top of your green zone. Be careful, because you could hit your tipping point. Be alert for further stress, and consider strategies to reduce stressors or increase your performance capacity.

The tipping point. Approaching your tipping zone is dangerous. If familiar tasks become harder, if your inbox is overwhelming, if you snap at reasonable requests or if you work longer with fewer results, you may be at your tipping point. At the tipping point, you still have time. You can think. You can experiment with one stress reducer at a time. Take action now to reduce your stress. Climb back down into the green zone while you can still think clearly.

The red zone. Passing your tipping point is catastrophic because of the accelerating downward spiral of performance. To get out of the red zone, aggressively implement stress management strategies. Make a plan that combines at least two or three big stress reducers – simplify, center, get support from your boss, delegate, etc. Make smart requests ask your boss for support or delegate. Whatever the details, take dramatic action. In the red zone, you must act now.

A lifeguard. I must confess: This red zone advice may not work. The downward spiral of performance undermines your decision making and behavioral flexibility. If you are drowning, sometimes you can’t save yourself. You need a lifeguard who will know you need help and step in during a crisis. Your lifeguard could be a friend, a mentor, a coach or your family. Before a red zone crisis, build strong relationships. Be transparent, accountable and open to constructive feedback. Then, if you are drowning in stress, you will have someone willing to dive in to save you.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for yourself and for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

The Tipping Point of Performance

Allen Slade

I love sports movies, especially about underdogs. The critical moment is when the coach or loved one gets the underdog fired up. I love Rocky II, when Talia Shire lights Rocky’s fuse from her hospital bed and Remember the Titans, when Denzel Washington gives a moving call for unity in the Gettysburg cemetery.

As a leader, do you try to fire up your team? Be careful. If you play with fire, you can get burned.

Clearly, there are times when you need to establish a sense of urgency. But asking for extraordinary effort can backfire. As the performance curve below shows, there is an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between stress and performance does hold, but only in the green zone.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

The problem hits at the top of the curve. When a person reaches the tipping point, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance leads to a downward spiral in the red zone. People become anxious. They act indecisively, work slower or make more mistakes. As their performance decreases, their anxiety increases, further decreasing their performance. Notice the red marble at the top of the performance curve. In the red zone, the marble accelerates down the curve of poor performance. As a leader, if you push a person too far, their performance drops. And, their performance will continue to get worse because of the downward spiral.

Bottom line: Push for performance, but avoid the tipping point for stress. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Aim for high performance, not peak performance. I coach leaders to avoid pushing people to their tipping point. If the tipping point is at 100% performance, aim for 90 or 95%. Then, your team member has a stress buffer. If there is a coffee spill that wipes critical data or a car wreck going to the big meeting, they will have the psychological reserves to get through it. If you push to get the full 100%, your people may tip into the red zone.

Develop your people. If you wish to increase performance, but a person is near the tipping point, think development first, motivation later. Increase their competence and capacity, so they can perform better while maintaining an essential stress buffer.

Be a lifeguard. Your people can drown in stress. The downward spiral of performance undermines decision making and behavioral flexibility. If someone is in the red zone, you may need be their lifeguard. Watch for signs of stress in your team members, watching for people at the tipping point or in the red zone. Then, throw them a life line. Offer more resources, renegotiate deadlines, offer them time off to refresh and rest. Be creative – think of the rousing speech that fires up the underdog, then do the opposite.

Know your team. Everyone is different. The people you lead have different capabilities and stress tolerances. They will show different warning signs of a stress-induced performance crisis. Get to know your people before a crisis. Have regular dialogue with every team member. Seek insight about their performance patterns, personal stressors and individual signs of overload. This will equip you to be a stress lifeguard.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

Smart Goals

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders set goals for themselves and others. The most powerful goals tend to be specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Here are my thoughts on how to set smart goals:

Specific – the goal states a specific outcome or action. If your goals are stated only as outcomes, there may be no obvious steps to take. You don’t want to be like the basketball coach who talks about winning but has no plan for today’s practice. If all of your goals are actions, you can get disconnected from your ultimate purpose, like the basketball coach who focuses only on holding a great practice. I encourage my clients to set a mix of outcome goals and action goals, covering both the end to be achieved and the means to that end.

Measurable – the goal can be assessed against an objective standard. We tend to value what we measure and measure what we value. Without measures, your goal is light-weight. The measures can be hard, in the form of objective numbers. Numeric metrics are straightforward, but easy to measure does not equal important. Your measures may need to be soft, in the form of assessments of key stakeholders. And some measures are binary: Did the desired activity or outcome happen (yes or no)? Different goals require different metrics, but all goals should be measurable.

Actionable – the goal can be acted on by the person who holds the goal. Your goals are powerful only if you can personally take steps to accomplish the goal. As a leader, set goals with your team that are in their realm of possiblity. Otherwise, you will undermine their motivation and your credibility.

Realistic – the goal is difficult but attainable. Harder goals increase performance. But goal difficulty has limits. When a goal becomes unrealistic, its power disappears. When setting goals for ourselves, you should think through your odds of success. When setting goals with others, have an open two-way discussion of the goal to get the level of difficulty right. Difficult goals are good, but they must be attainable.

Timebound – the goal has clear timing, either a date or a rate. For one-time goals, use a due date. “I will accomplish this action by April 1 of next year.” For ongoing goals, use a rate of action or outcome. “I will sell $100,000 of new consulting business per month.” Without a date or rate, a goal is not specific or difficult.

With all five smart features, your goals will have maximum impact. And, all five feature should reinforce each other. The specific actions should be realistic, the metrics should have a date or rate, etc.

It is possible to go overboard – to be too smart for your own good. With my leadership coaching clients, less is usually more. At first, I encourage them to focus on just one or two behaviors to change. Taking on too many changes creates frustration rather than change. We often start with goals that are general. For example, a client increasing visibility might start with “Notice how much airtime I take up in meetings.” This is not specific, but sometimes that is all that is needed to trigger change. If a stronger trigger is needed, we move to a more specific goal, such as “I will speak up twice in every meeting.” If that doesn’t works, we can move to an even smarter goal, such as “In Monday’s meeting, I will comment twice on product quality. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story.”

Almost every goal could benefit from being a bit smarter. Yet consider what works for you. Some people thrive on smart goals tightly linked to their life purpose and their daily schedule. Others need nothing more than a Post-it reminder. And, once your goal is in play, notice how it works for you. If you are making progress and accomplishing what you want, that goal is right for you. If your goal is not working, consider making your goal smarter.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

It is also important to agree on metrics and time for each goal at the beginning. Then, during the peformance review, you and your team member will be on the same page with feedback.

Bottom line: You should set specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound goals, for yourself and for others. When setting goals with others, have lots of dialogue. Be smart – create dialogue, insight and powerful goals to drive performance.

Steps for Planned Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

A model for planned change can help you navigate your way through uncharted territory. There are a lot of different change models out there, and many of them are numbered. Here is a partial list:

As a change leader, should you use a change model? If so, which one?

The bottom line: Use a planned change model. As for which model, go with what works for you and know when to yield.

I generally recommend a planned change model for my clients. A model can help simplify a complex situation, provide a common language for discussing change in your organization and can focus attention to guide action. In other words, a planned change model gives insight for intelligent change.

There are differences in the number, sequence and timing of the steps, but these differences are not very important. Which planned change model you use is a matter of preference and politics. If your preference holds sway, use what works for you. If the powers that be insist on a different model, you can yield with a clear conscience. I have scars from arguing too hard for change models that were not in vogue. Almost any planned change model will help chart your course through the change.

John Kotter’s 8-step model for leading change works as well as any, so I use it often. Here are his eight steps:

1. Establish a sense of urgency. I recommend an analysis of the forces for change and the forces for stability. If the forces for change are not great enough, regroup and restart.

2. Form a powerful guiding coalition. Get the right people with sufficient knowledge, influence and commitment to guide the change. If you initiated change without the juice to make it happen, get the power brokers on board.

3. Create a vision. This should be a powerful, brief and memorable summary of the change – what is changing, why and how it affects us. A fuzzy vision will make the rest of the process harder.

4. Communicate the vision. Get the vision out there and get all parties to join the process. But don’t see communication as a “tell and sell” campaign. Engage in dialogue. Underscore the key points and get your employees’ feedback, insights and creativity. Change your plan early and often based on this dialogue.

5. Empower others to act on the vision. You can’t do it all. Bet on your people. Encourage them to act without your tight control. The vision for change sets the boundaries and general direction. Let others sweat the details.

6. Plan for and create short-term wins. Change is hard work. Change is especially hard in the middle, after the initial excitement has died down and before the final success is clear. Discouragement must be managed. Celebrate your team’s success early and often.

7. Consolidate improvements and produce still more change. Build on your success. Leverage your successes and learn from your failed experiments.

8. Institutionalize new approaches. Lock in the new way of doing things with congruent changes to your strategy, structure, systems and culture.

If this 8-step model resonates with you, use it. If not, look for another planned change model. A good road map provides insight for intelligent change.

Faster Change is Your Only Advantage

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

In my post on Making Sense of Change, I highlighted the need to devote energy to sense-making during seasons of change. As a leader, how long are your seasons of change? When will things get back to normal?

The rate of change is accelerating. Moore’s Law originally applied to transistors, but the pattern of exponential change affects every process and every corner of your organization. Everything is accelerating – bigger changes, more changes, at a faster pace. Even the pauses are disappearing. When you complete a major change, you are likely to move on to the next change.

Bottom line: Change is the new normal. And your only sustainable competitive advantage is your ability to change faster than the competition.

Your organization’s ability to survive depends on its reflex time. You will prosper as a leader if you are on the front edge of change. And your team needs to get on board with the new normal.

Let’s think through the commitments, competencies and capacities needed for faster change.

Commitment to change. Change is here to stay. Don’t waste energy complaining about the latest change or wishing for past stability. Embrace the change. Look forward to change. Jump into the next challenge.

As a leader in the midst of change, you help set the tone for your team. Be a cheerleader for change. Get others excited about the bright future.

Growing change competence. As change accelerates, you need to be better at change. Treat every change as an opportunity to master new skills. Look for new ways of doing things. Be the first to tackle the new challenge, play with the new system, apply the new concept or talk to the new person. Today’s change is practice for tomorrow.

As a leader, you need to develop your team’s change competence also. Coach them in change competence. Take risks with your team’s decision making – empower them to act without your tight control. Their growth today will make tomorrow’s change easier for both of you.

Capacity to change. It is not enough to be able to change. You need the capacity to change quickly and often. You have to multi-task competing changes. You must accelerate your sense-making so you can quickly climb out of the performance valley of change. And, you cannot rely exclusively on carefully planned change. You need to able to “ready, fire, aim” and just do something.

As a leader, you need to encourage your team’s capacity to change. Push your team to the point of change fatigue. Help them be quicker at sense-making. Get them to move beyond planned change so they can just do something. Then, their change muscles will have more capacity the next time.

You increase competence by mastering new skills. You increase capacity by using those new skills over and over again. I mastered the basic competence of riding a bike many years ago. I recently rode my first century. It was a major challenge to bike a hundred miles in one day. I needed commitment, competence and capacity. I had to commit to finishing the ride. I had to master newer cycling technology – a new road bike instead of my trusty old hybrid, shoes that lock into the pedals and sports drinks that taste like cold sweat. And, most importantly, I had to increase my capacity to go longer and faster by riding hundreds of miles before the actual century.

The demands of change are massive. Dialogue and rest can help you avoid be overwhelmed.

Dialogue. Surround yourself with people who support and encourage you in times of stress.

- Rely on your family members and close friends for encouragement. Talk about your changes. Talk about the impact on you physically, mentally and emotionally.

- Form a circle of trusted advisors with whom you can talk through the challenges and your change approach.

- Consider getting yourself a leadership coach.

Rest. Take a break from the relentless pace of change.

- As needed, stop and catch your breath. Consider using centering or some other activity to still your hands, quiet your mind and calm your heart.

- Schedule times of rest. Every Sunday, I take a sabbatical from work – largely avoiding email, Twitter and this website. I catch up on sleep that day and I think about the big picture. On Monday morning, I am ready to accelerate back onto the change expressway.

As a leader, you must also provide dialogue and rest for your team. If you are pushing them to the point of change fatigue, make sure they recover well. Support them in the midst of change. Talk about the change. Support them with advice. Thank them for their efforts. And, give some breathing room for them to recuperate.

Change is the new normal. The rate of change is accelerating. Your ability to change faster than the competition is your only sustainable competitive advantage. If you are overwhelmed by change, take a quick break right now. Then get a little help from your friends.

Making Sense of Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Can you perform at your maximum – can you give 100% – in the midst of change? Should you demand 100% from your team when they are facing change? Pushing hard for short term performance can undermine long term success and maximum growth. We need to leave breathing room for change to work its way out. We need to plan for a season of sense-making.

Meryl Louis defines sense-making as the psychological process of revising our cognitive map to figure out “what is new, different and – particularly – what was unanticipated.” Sense-making rewrites a large cognitive map:

- Understanding new duties, responsibilities, power structures, and peer relationships.

- Clarifying the new path to success, including new performance criteria and new goals.

- Developing new skills and behaviors to master the new role.

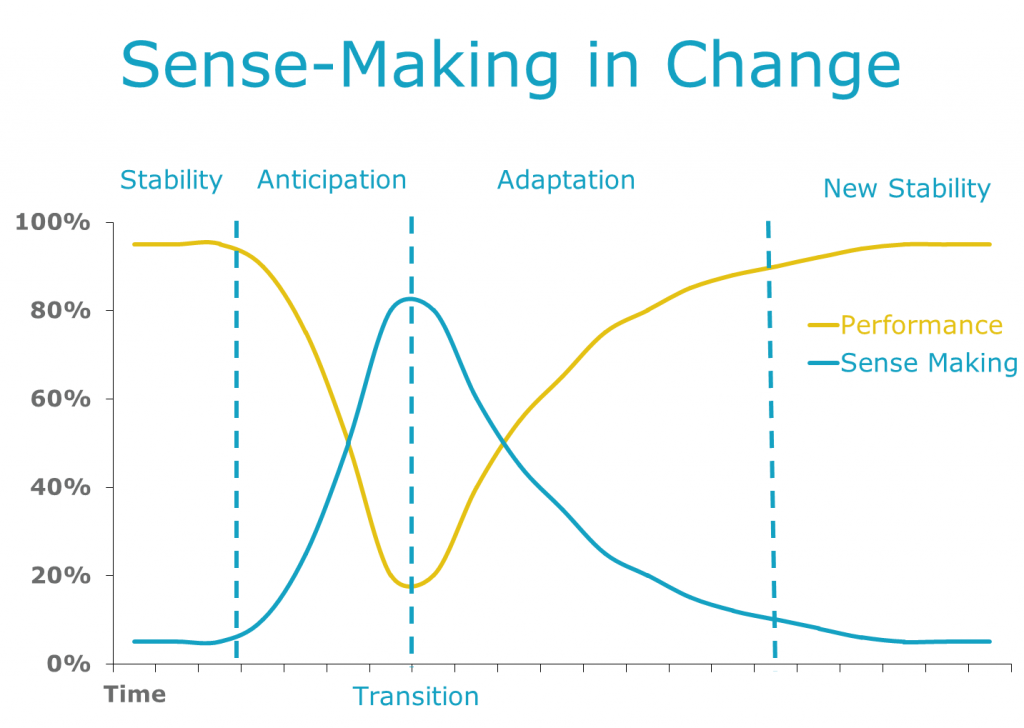

Here is a picture of sense-making in action:

When you go through a transition, you should expect a decline in performance. You will need to spend energy and time making sense of the new situation. In the midst of change, I ask my clients two questions:

How deep is your valley? The larger the transition, the deeper the expected decline in performance. A reorganization which just moves some boxes on the org chart will have little impact on your performance. A major change of systems, strategy, structure and culture will require more sense-making.

Where are you on the sense-making curve? The highest level of sense-making tends to occur at the point of transition. The hallway conversations linger longest the day the new strategy is announced. The job change is nested in farewell lunches and new employee orientation programs to give breathing space for sense-making.

When you lead others through change, you should plan for your team’s sense-making. This is tough when the change is triggered by competitive pressure. No matter what the performance demands, you can’t just wish away the need for sense-making. During the change, help your team through the valley. Give them perspective, just-in-time information and support to help move them to the other side.

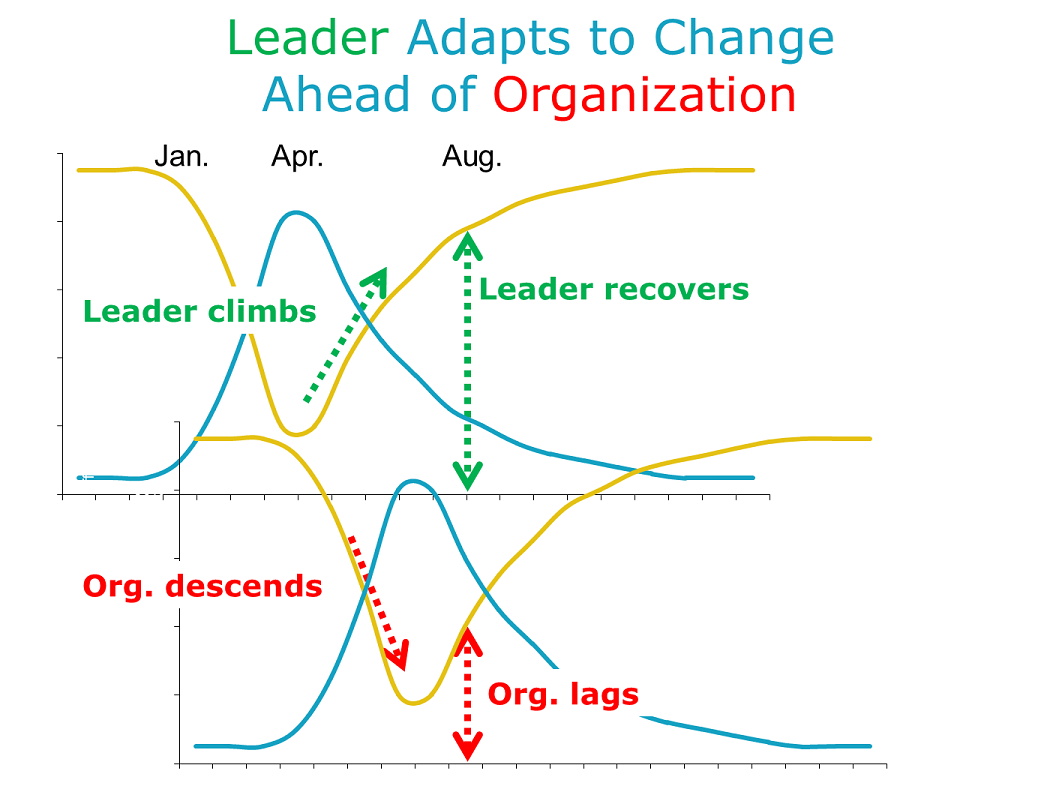

If change is rolled out top-down, the change leader will be further along the curve. You start planning a change in January and announce the change in April. You will be at the peak of sense-making and stress at the April announcement, but your organization is just starting the process. By August, your performance is almost back to pre-change levels, but your organization is just bottoming out.

This lag in sense-making can cause frustration and impatience. As a leader, you can falsely blame your team for not getting with the program. The reality is they need more time because they started the transition after you.

As a leader, plan for the season of change. Know where your people are. “How deep is their valley?” “Where are they on the sense-making curve?” Truly lead, not just in planning the tasks of change but also in making sense of the new future. Provide perspective, just-in-time information and breathing space to help them climb the far side of the sense-making valley.