When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Integrity and Change

Allen Slade

In Faster Change is Your Only Advantage, I wrote about three C’s you need to master for change:

Commitment. Embrace the change. Look forward to change. Jump into the next challenge.

Competence. Become better at change. Grow by tackling new challenges, playing with the new system, applying the new concept or talking to the new person.

Capacity. Be able to change quickly and often. Multi-task competing changes. Be able to manage carefully planned change, but also be able to “ready, fire, aim” without detailed plans.

These C’s are still important. But there is a fourth C:

Character. Be known for your integrity and compassion.

We will look at compassion in our next post. Today’s focus is the need for integrity in the midst of change.

Your integrity as a leader should be rock solid at all times, especially during tough transitions. To be known for integrity, you should be a truth teller and a promise keeper.

Truth tellers mean what they say and say what they mean. They avoid both active deception and passive deception.

Being a truth teller does not mean that you violate confidences. Sometimes, managers are privy to information that they cannot share with their team. For example, during a reorganization, employees may ask if their jobs are secure. If layoffs are possible, do not falsely reassure employees. But you also should not jump the gun. Instead, you may have to say “I don’t have any information to share with you at this time.”

Promise keepers make strong promises and keep them. Chalmers Brothers distinguishes three kinds of promises:

“Strong promises: Promises that I am absolutely committed to keeping. You can count on me.

“Shallow promises: These look like a strong promise, but what I don’t say out loud is ‘unless X or Y happens.’ . . . Here, we reserve a private ‘out’ for ourselves, but we don’t let the other person know.

“Criminal promises: These are promises that at the moment of making, we know we have no intention of keeping.”

A reputation for integrity requires making strong promises and keeping them. Then, people will know you are as good as your word.

Promise keepers may find it necessary to revisit agreements when conditions change. The key is how you change the agreement. If you cannot keep a promise, you should proactively go to the other party and attempt to negotiate a new agreement that is acceptable to both of you. Then, people can rest easy in your integrity. They know you will not forget your promises or unilaterally change your commitment.

Contrast a promise keeper with people who do not make strong promises:

They may avoid strong promises by saying “Sounds good.” or “I will try to . . . .” They may keep a private “out” that excuses them from keeping a promise. Or they may make a criminal promise with no intention of keeping it.

Shallow promises, private outs or criminal promises damage your reputation. Avoid them by keeping your promises.

Bottom line: Treat people with respect by telling the truth and keeping your promises. They will follow you confidently during today’s change and the changes to come.

If you do not have the reputation you want, start building credibility today. Tell the truth when a lie would be easier. Keep a promise that hurts. Proactively renegotiate a commitment that you have the power to ignore or unilaterally change. Building your reputation takes time and repeated testing under pressure. Be consistent and patient to grow your reputation.

If you are already known for your character, protect your good name by continuing to be a truth teller and a promise keeper. Then, your character will complement your commitment, competence and capacity to change.

At the Gaps, Go Slow to Go Fast

Allen Slade

In organizations, faster change is your only long term advantage. But sometimes, speed prevents people from making the change successfully. By going fast, you create errors and friction, causing the change to be less successful.

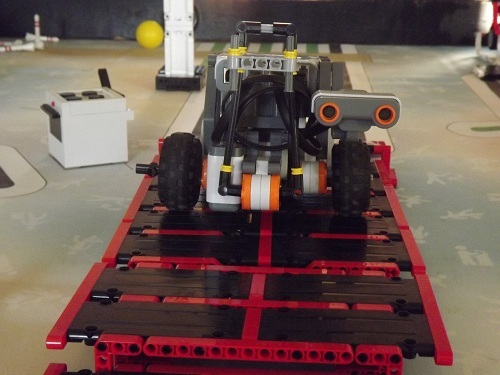

My sons are on a team in the FIRST Lego League robotics competition. They program a wheeled robot to hit levers, fling a ball and grab things. The final task is to drive up a ramp and park on a teetering platform.

The robot must be centered or the platform will tilt and the robot will fall off. The robot’s behavior is unpredictable, especially at gap between the ramp and the parking spot.

When you are leading change, do you go too fast? Do you “program” your team to slam through obstacles as quickly as possible? You can go fast to go slow. Don’t be surprised if your change goes off track.

When you are leading change, do you go too fast? Do you “program” your team to slam through obstacles as quickly as possible? You can go fast to go slow. Don’t be surprised if your change goes off track.

The solution? Slow down at the gaps.

The robotics team reprogrammed the robot to climb the ramp slower. To jump the gap, they slowed the robot down even more. Jumping the gap is less violent and the robot is less likely to be thrown off kilter.

Bottom line: Go as fast as you need for change. But if your change is going off track, go slow to go fast.

As a wise change leader, you need to know when to go slow and when to go fast. At the major transition points, allow people time to make sense of the change they face. By taking the time for dialogue and insight, you can create intelligent change. Go slow to go fast, and you can increase the odds of reaching your goal safely.

Jobseekers, Brand Yourself as a Servant

Allen Slade

In cover letters, resumes and interviews, jobseekers often give reasons that they want or need a job. “I am seeking a rewarding career in . . . .” “I enjoy . . . .” “I would like to apply for your opening in . . . .” “I am reentering the workforce after . . . .” While these phrases are not illegal, immoral or ungrammatical, they are a bit self-centered.

Career success does not flow from your needs alone. You will be hired to serve, not to be served. You will succeed when your interests and abilities line up with the organization’s needs. The sweet spot for your career is when ability, affinity and opportunity meet.

Hiring manager focus on the intersection of the green and blue circles. For hiring managers, affinity is a lesser priority than your ability to do the job. They want your competencies, capacities and commitments to solve their problems.

So, how do you shape a hiring manager’s perception of your ability to do the job? Managers quickly form an impression who you based on incomplete information. As I posted in The Problem with Your Personal Brand:

When you walk through the door, who shows up for the other people in the room? What image do people have of you? When I walk in, I would like to think that the “real” me shows up. Unfortunately, who actually shows up is an imperfect memory of me. . . . If only a partial image of the “real” you shows up when you walk in the room, you need a brand and a plan. You need a personal brand statement like this:

For [a specific person or group], I want to be known for [six adjectives] so I can deliver [valuable outcomes].

Bottom line: When seeking a job, brand youself as a servant. Hiring managers care about your ability to deliver valuable outcomes.

I advise my career coaching clients to take three steps before every job application:

1. Research. Investiage every job thoroughly before you apply. Go beyond studying the industry and the position itself. Figure out what problems keep the hiring manager awake at night.

2. Target your brand. Figure out the six adjectives that accurately describe your competencies, capacities and commitments to help solve those problems.

3. Articulate your brand. Then, craft your application and your interview responses to give a powerful brand message: Hire me and I will help solve your problems.

If you take these three steps, the hiring manager will be favorably inclined to pursue you as a candidate. And, you are likely to get the career outcomes you seek – meaningful work, concrete rewards, an opportunity to grow – because you are serving the organization well.

The Problem with Your Personal Brand

Allen Slade

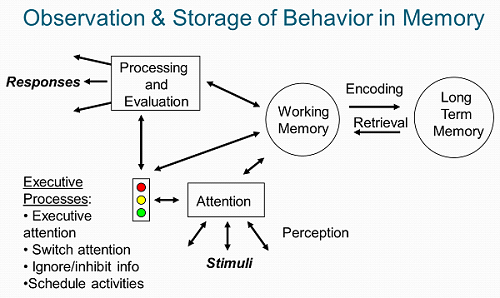

When you walk through the door, who shows up for the other people in the room? What image do people have of you? When I walk in, I would like to think that the “real” me shows up. Unfortunately, who actually shows up is an imperfect memory of me. Here’s a picture of the cognitive process of what people remember about you:

Bottom line: The problem with your personal brand is every step of cognition simplifies and distorts the memory of who you are. As Leonardo DiCaprio’s character in the movie Inception says: “But I can’t imagine you with all your complexity, all your perfection, all your imperfection.”

If only a partial image of the “real” you shows up when you walk in the room, you need a brand and a plan. You need a personal brand statement like this:

For [a specific person or group], I want to be known for [six adjectives] so I can deliver [valuable outcomes].

For example, here is part of my own personal brand statement:

For my leadership coaching clients, I bring powerful listening, insightful curiosity and straightforward knowledge to create maximum leadership presence, personal effectiveness and organizational success.

Here are some suggestions on how to craft your own personal brand statement:

Target your brand. You should have a targeted personal brand statement for each group or person you want to impact. For myself, I have three brand statements. You need at least two brand statements.

Be organized. Gather all the data about how others perceive you – performance reviews, personality profiles, 360 feedback, key emails, verbal impressions, etc. Then take at least four hours spread over several days to draft your personal brand statement. Here is a personal brand worksheet to help you get started on defining your own personal brand statement.

Be authentic. Make sure your personal brand is completely compatible with the real you. Being authentic moves your personal brand from false advertising to true marketing. If your personal brand promises what you can actually deliver, you and the people you serve will be happier.

Get feedback. Once you have a draft of your personal brand statement, share it with your circle of trusted advisors. Their reaction to your brand can help you test its authenticity and its value to the people you want to serve. Your circle of trusted advisors should include mentors, spiritual advisors and, ideally, a certified career coach, leadership coach or executive coach.

When you craft a personal brand statement, you help focus the impressions others hold about you. You open doors to new leadership and career opportunities. Then, when you walk in the room, “who shows up” for the other people is the authentically influential you.

Principles of Leadership Are Outdated

Allen Slade

When I teach leadership to business students, I often open the first class by asking students about leaders they respect. Mahatma Gandhi, George Patton, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Steve Jobs are often mentioned. Some students talk about their athletic coach or a former boss.

Then, we get to the heart of leadership. To save you the cost of tuition, here are the highpoints:

The “Great Man” theories of leadership don’t work.

There is no one best way to lead. The best way to lead depends on the situation.

The best leaders are not students of leadership.

There are no simple rules. I discourage imitating role models. I attack leadership trait theories. I undermine leadership style theories. Being the best leader you can be is difficult and complicated.

Those who look for simple answers are understandably disappointed.

Yet, there is a straightforward approach to leadership in my class. Be a student of followership and collect lots of data.

Be a student of followership. Don’t waste time studying leaders or leadership. Study the people you lead. The best leaders have incredible curiosity about the people around them. They ask people what’s important to them, then they think hard about the implications. They check for understanding by asking more questions. The best leaders shape their leadership behavior for their followers.

Collect lots of data. To understand people, the best leaders are hungry for information. They collect data with direct observation of the words, tone and emotions of others. They ask lots of questions. And they suck every bit of value out of any quantitative data they can get, through surveys, 360 reports, attrition data, customer data, etc.

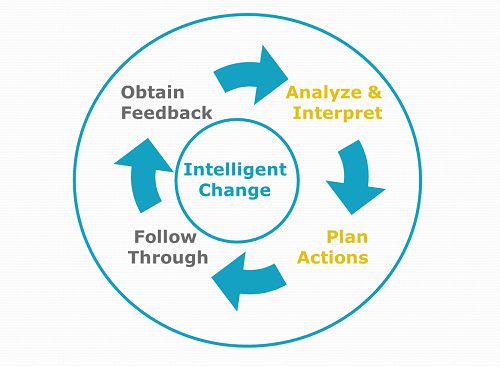

For the visually oriented like me, here is how I capture this vision of leadership:

With a commitment to know the people you lead and a hunger for more data, you can bootstrap your leadership. You can create mini-experiments based on your tentative knowledge of people, and then correct your actions based on their feedback. You will develop a personal, flexible leadership style. And, I suspect, your impact as a leader will expand well beyond what you would achieve if you had simply tried to imitate the great leaders of the past.

Managing Negative Deviance vs. Leading with Appreciation

Allen Slade

In our culture, pragmatism runs deep. We see through the lens of problem solving. We look for negative deviance by measuring performance against standards and focusing on shortcomings. We identify weaknesses and we punish shortfalls. We hold others accountable to meet standards. If someone does not measure up, we take corrective action. If someone does meet one set of standards, we look for other areas where they have fallen short.

Yet, as a leader, you are responsible for the debris field of negative deviance. Too much control, too much problem solving undermines your team’s engagement. If you are always focused on problems, your team will lose energy. As I said in The Problem with Problem Solving:

If a given task or situation seems to be laden with problems, you lose energy for that task or situation. External factors (such as a paycheck) may cause you to continue with that relationship, task or situation, but your heart won’t be in it. Excessive problem solving is the problem.

If problem solving drains energy, appreciation builds energy. You must be able to appreciate people and opportunities. You must be able to recognize what is good, true, effective and beautiful. You must reward progress, not just punish shortfalls.

As a leader, what can you do to help your team maintain the right balance between problem solving and appreciation?

One buffer to negative deviance is leading with appreciation. As a leader, you should look for what is good, true, beautiful and effective. You must help your team members leverage their strengths, not just fix their weaknesses.

I encourage you to try powerful questions to lead with appreciation. The right questions can help shift your team’s focus from problem solving to building on what works well. Pull out the positive by asking:

What is going well? What is better than expected?

What are we doing right?

How are we better than the competition?

Where have we improved? What have we learned?

How can we build on our strengths?

Leading with appreciation will help shake your team out of persistent problem solving. Your team will discover best practices and build on existing knowledge. As your team gets better at appreciation, they will discover sustainable success.

You will also see an impact on your team’s energy. People will engage because they are involved in success, not just a series of problems.

As a leader, your job is to manage energy in others. Try less management of negative deviance and more leadership with appreciation. Then stand back and enjoy the sustained power surge.

The Problem with Problem Solving

Allen Slade

“We have a problem.” If someone says that, do you get a sinking feeling? If you bring up problems with your team, do you feel the energy leave the room?

Let me be clear. Problem solving is good. As a leader, you must solve problems. Your ability to find and fix flaws is essential. Leaders need to find the error, reverse the decline, criticize the fault, hold others accountable and hold difficult conversations.

The problem with problem solving is that we use it too much. Relentless fault finding decreases energy for you and the people around you. If you see everything as a problem, you drain your own energy. If a person frequently finds fault with you, you lose energy for that relationship. If a given task or situation seems to be laden with problems, you lose energy for that task or situation. You may need to continue in that relationship, task or situation, but your heart won’t be in it. Excessive problem solving is a problem.

While problem solving drains energy, appreciation builds energy. As a leader, you must be able to appreciate people and opportunities. You must be able to recognize what is good, true, effective and beautiful. You must reward progress, not just punish shortfalls.

To manage the energy of the people you work with, be mindful of your appreciation ratio. The tipping point seems to be 1/3 problem solving to 2/3 appreciation. When problem solving exceeds 1/3 of interactions, we tend to lose energy for that person, task or situation. When appreciation is 2/3 or more, we tend to build energy. Aim for an appreciation ratio of at least 67%.

Managing my own appreciation ratio has fundamentally changed my outlook on life. I used to see consulting as problem solving. If my client hired me to solve problems, then I had to be scanning for problems, thinking about problems, talking about problems and solving problems. With my problem radar on full power, it is no surprise that I found lots of problems. I completed many consulting assignments thinking “With all these problems, I’m glad I don’t work here.”

Now, I look at my clients from the perspective of success. I look for my client’s strengths – what is good, true, effective and beautiful about what they do. With my appreciation radar on full power, I appreciate my clients more and I project a positive vibe. I still solve problems, but I solve them in an atmosphere of appreciation. Now, when I complete an assignment, I think “This is a great company!”

There is a strategic problem with a low appreciation ratio. Focusing on strategic weaknesses is more than depressing. It is bad strategy. Ford Motor Company got into retail banking in the late 1980s and 1990s. Ford was good at car loans and leasing, but it was not very good at retail banking. A problem solver would work on banking until it was fixed. Ford tried to turn the banks around for a few years , but the company wisely decided to cut its losses and sell the banks. Then, Ford was able to focus on its core competencies in auto financing and manufacturing.

Try a mini-experiment today: focus on what is good, true and effective. Look for strengths more than problems. When you interact with people, notice your appreciation ratio. When it drops below 67%, turn down your problem radar and turn your appreciation radar on full power. In the short term, you will perceive things more positively. In the long term, you will build stronger people, more effective systems and a healthier organization by leveraging competency rather than focusing on failure.

To solve the problem with problem solving, go positive. Problem solve less and there won’t be as many problems. Appreciate more, and you will build your success as a leader.

Test Your Ejection Seat

Allen Slade

Felix Baumgartner’s space jump had a dramatic buildup to a truly amazing physical feat. The video of Baumgartner spinning and tumbling at 700 m.p.h. is heart wrenching. And it ended with a perfect landing.

However, the “mission” was presented as a NASA-like experiment to make space jumping viable for escaping from a space vehicle. The mission was not very NASA-like. The flight director was no Chris Craft. And Baumgartner is an extreme athlete, not an astronaut. His poor checklist discipline and his concern with styling his hair after removing his helmet was more Tom Cruise than Alan Shepherd.

My father, Harry Slade, worked at NACA/NASA from the beginning of the jet age through the space shuttle. And, in 1976, in the New Mexico desert, he helped test one of the oddest emergency systems in the world: a helicopter ejection seat. How does Baumgartner’s space jump compare to a helicopter ejection seat?

The best ejection seats are virtually automatic – pull one lever and hang on. Baumgartner’s exit was slow and difficult: a long checklist and keeping his cool while tumbling at 700 m.p.h. But Baumgartner did not jump from a hypersonic spacecraft. He bunny hopped from a capsule floating gently beneath a balloon.

Space jumping will require more planning and testing before it provides real safety. In an emergency space jump, the craft would probably be spinning, disintegrating or on fire. A Baumgartner-like jump would be too complex and too physically stressful for a space tourist to survive.

NASA’s helicopter ejection seat was not like the space jump. The ejection seat was for a helicopter testing next generation rotor blades. Test rotors were thinner and lighter, increasing the risk of failure. Rotors are most likely to fail during takeoff and landing. A pilot could not eject down because of the low altitude. The pilot cold not eject sideways either, because rotor debris would be spiraling to every point of the compass. The ejection seat had to go up, through the path of the rotors. The ejection sequence was complex: pull the ejection handle, blow off the rotors with explosive bolts, blow the hatch, eject the seat, cut the seatbelts, then deploy the parachute. Asking a pilot to remember these steps during a crash was a recipe for failure. The pilot’s only job was to pull the ejection handle and let the automatic system do the rest.

For leaders, when the crisis happens, it is usually too late to build an ejection seat. When time and tempers are short, people go into survival mode. The brain shuts down cognitive processes, attention narrows and choices seem limited to fight or flight. What backup plans do you need to create? Your leadership crisis may be the loss of a key employee, an unexpected customer request, failure of essential equipment or overload of a critical operation. If the crisis happens quickly, you need to already have an ejection seat.

For a job interview in 2002, I made a presentation on leadership. I emailed my presentation to the host. By plan, I arrived 15 minutes early to check the room. When we turned everything on, my presentation was not on the laptop and my host did not know how to transfer the file. (It was 2002.) No problem – I had a floppy disk. (No USB in 2002.) She found an external disk drive, but the drive did not work. No problem – I had transparencies. They found a dusty overhead projector. When we turned it on, the bulb did not work. No problem – I activated the built in back up bulb. The second bulb worked. I tested the projected image, focused the projector, focused my emotions and was ready to go. (I had one more backup if the second bulb blew – use the whiteboard.) The presentation went well, and I was offered the job.

Lesson #1: For critical activities, have multiple backup plans before the crisis.

The helicopter ejection seat offers another lesson. My dad was in New Mexico to test the seat. The helicopter was bolted to a jet sled, accelerated to flight speed, then a test dummy was ejected. The first test was almost right. The rotors did not blow off before the seat was ejected, shredding the test dummy. (A watching test pilot walked away saying “I’m never flying that bird.”) The NASA team found and fixed the flaw in the timing circuits. All the other tests were successful.

When I joined Microsoft in 1999, my key task was to make the employee opinion survey a success. The 1998 survey locked up because of overloaded servers at the survey host. Under my direction, we created backup plans for every problem we could imagine. More importantly, we tested our back up plans. We did load testing, usability testing, data integrity testing and translation testing. We even tested our testing. In effect, we accelerated the survey to flight speed and pulled the ejection handle. The testing identified problems that we fixed, then we tested to the point of repeated perfection. The actual survey went well – on time, with virtually 100% uptime.

Lesson #2: For critical activities, test your backup plans before the crisis. Make the tests as realistic as possible. And test your tests.

As a leader, what are your key processes? How can they fail? What are your plans for overcoming failure? And how well tested are those plans?

Don’t rely on extreme leadership ability in a crisis. Few of us can tumble at supersonic speed like Felix Baumgartner. Plan for failure and test your plans until you know your ejection seat will save the day.

Leading in Stormy Weather

Ben Slade

In the early 1980s, the Bell Telephone Company was convicted of antitrust violations and broken up into several “Baby Bells.” Frequent reorganizations, constant rumors, and a lack of job security took a toll on the workforce. Many employees were overwhelmed by the stress. They experienced physical, mental, and emotional strain at work and at home. However, some employees emerged from the deregulation with an increased sense of energy and vitality. These hardy survivors proceeded to make meaningful contributions both inside the company and out. What distinguished the overachievers from the overwhelmed?

Prolonged or intense stress can put employees at increased risk of illness, marital problems, and reduced productivity. However, some individuals emerge from very stressful events relatively unscathed. Understanding stress vulnerability can help identify opportunities to create pathways to resilience.

One pathway to stress resilience is hardiness. Hardiness has three components: commitment, control, and challenge. Hardy individuals are committed to their organization, finding meaning and stimulation from the work that they do. They believe they can exert control on the world around them, and that their fate is not predetermined. Finally, they interpret difficult experiences as challenges that lead to growth and maturity, and are willing to persist in a difficult environment rather than flee for temporary comfort.

If you are a hardy leader, you will typically excel in stressful circumstances. Although you can sometimes reshape your environment to reduce this stress, you are often surrounded by challenges that are difficult or impossible to change. Your own responses will probably not change the technological limitations, economic recessions, or government regulations that boost your stress levels.

Hardiness is like a rain jacket, deflecting the rain without changing the intensity of the storm. You may not be able to control the environment, but a predisposition towards positive thinking and action can protect you from getting wet. By reframing hard times as an opportunity to excel and conquer, you actually boost your own resistance to stress.

As a leader, your hardiness may even be an umbrella for your team. This hardy leader influence is driven by social sense-making. You can increase your team’s stress resistance with your own behaviors and attitudes.

Transformational leaders inspire and motivate their followers by reframing obstacles as opportunities. Often, you cannot eliminate stress in the workplace. Instead, you can reinterpret stressful circumstances as opportunities to excel. Emotions which can interfere with performance (such as anxiety) can be translated into excitement. When you motivate your team to commit to achievable goals, help them believe that they control their own destiny and demonstrate how obstacles are challenges instead of threats, you have extended your umbrella of hardiness. You bolster individual resilience and improve organizational performance in the face of uncertainty and change.

Do you interpret events in a hardy manner? Do you convey the right messages to your subordinates in the face of uncertainty? You can’t avoid the storms of change, but you can use commitment, control and challenge to help you and your team stay dry.

What to Expect from Career Coaching

Allen Slade

How can you find your dream job? Professional golfers, Olympic athletes and leaders all use coaches to maximize their performance. To accelerate your career success, consider adding a career coach to your search strategy.

Work takes up half your waking hours. If work is not going well – a toxic boss, a dead-end job, unemployment or underemployment – life tends to follow. In a booming labor market, new jobs are low hanging fruit. But in our current economy, you need a ladder to pick the apples at the top of the tree. You need a career coach.

A career coach is more effective than a teacher or mentor at stretching you to your best self. Your coach assumes you are the expert on your own career. Your coach will help you create a career plan and pursue opportunities effectively. And, a career coach will help you hold yourself accountable for meeting your career goals.

With my clients, we usually start with the ability, affinity and opportunity that make up their dream job.

Balancing ability, affinity and opportunity leads to long-term career success. If you focus on getting the highest paying job by matching your abilities with your opportunities and you ignore what you enjoy, you could end up in a dull job. If your focus on doing what you enjoy and do well, you could end up chasing disappearing opportunities with low pay, such as in the newspaper industry. If you focus only on high paying jobs you would enjoy, but you don’t have the required ability, you will never get a job offer.

A career coach will help you balance ability, affinity and opportunity. Coaches treat you as the expert in your own career, so they won’t direct you down a path you don’t like. They will help you find your own way. Coaches also have the ability to give gentle but powerful feedback on your plans. If you wish to pursue a new field, a good career coach will help you test your plans more gently than Monty Python’s vocational guidance counselor.

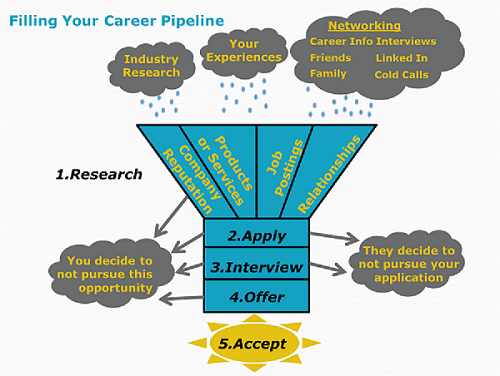

When you have identified your career direction, your coach will help fill your career pipeline. Your coach helps you expand your network, generate job leads, polish your resume/LinkedIn profile, target your applications, refine your interviewing skills and make the best decisions on job offers.

Like any professional service, fees for career coaching can be an issue. The payoff from career coaching is immense. It leads to higher satisfaction, more fulfillment and more pay. If you can afford career coaching, you will find it a worthwhile investment.

Like any professional service, fees for career coaching can be an issue. The payoff from career coaching is immense. It leads to higher satisfaction, more fulfillment and more pay. If you can afford career coaching, you will find it a worthwhile investment.

What if you can’t afford career coaching? If you are a recent college graduate, I recommend using your alma mater’s career center. If you are leaving a company, negotiate for career coaching as part of your outplacement package. You can also check to see what career development services are available from your state or local government.

Whatever you do, don’t settle. Don’t resign yourself to a dead-end job or unemployment. Don’t tolerate a poisonous work situation. Don’t say yes to an unattractive job offer. Pursue your dream job with the dedication of an Olympic hopeful. Fine tune your search skills like a professional golfer on the driving range. And, invest time and money to get the best career coaching you can get.