When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

The Problem with Feedback

Allen Slade

Most of us readily accept praise. But leaders can struggle with accepting and acting on constructive criticism. They can balk at negative feedback. Sometimes, it is reasonable to reject feedback because of its low credibility or irrelevance. However, habitually rejecting feedback suggests a deeper pattern – a world view that sees feedback as a problem.

Let’s get personal. How you respond to negative feedback?

Recall the last time you got substantial negative feedback on your work performance or professional relationships from your manager, colleague or close friend at work. How did you react?

1. I saw the feedback as an attack or threat.

2. I saw the feedback as disapproval or judgment.

3. I defended myself, denied the feedback was valid, or delayed receiving the feedback.

4. I accepted the feedback, even though I wanted to do well.

5. I welcomed the feedback.

6. I invited additional feedback.

Suzanne Cook-Greuter lists seven ways to respond to feedback[1]:

Opportunist. Focuses on own immediate needs and opportunities. Values self-protection. Receives feedback as an attack or threat.

Diplomat. Focuses on socially expected behavior. Values approval of others. Sees feedback as disapproval or judgment.

Expert. Focuses on expertise, procedure and efficiency. Values expertise in self and others, but takes feedback personally as an attack on own expertise. Defends, denies, and delays feedback, especially from lesser experts.

Achiever. Focuses on delivery of results. Values effectiveness, goals and success. Accepts feedback if it helps achieve personal goals and improve effectiveness.

Individualist. Focuses on self interacting with the system. Individual purpose and passion are more important than the system. Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of their own behavior.

Strategist. Focuses on linking theory and practice. Looks for dynamic systems and complex interactions. Invites feedback for self-actualization.

Magician. Focuses on interplay of awareness, thought, action and effects. Values transforming self and others. Views feedback as natural and essential for learning and change.

Today’s post focuses on opportunists, diplomats and experts – those who have response 1, 2 or 3 to negative feedback. Let’s look at each in more detail:

1. An opportunist lives for the moment, seeking passion with little long-term purpose. Since feedback is painful, the opportunist sees it as an attack or threat.

2. The diplomat wants to get along well with others. Feedback is disruptive. The diplomat prefers smoothing over differences.

3. Experts do not like feedback in their area of expertise, because it undermines their expertise. An expert will grudgingly accept feedback from a superior expert, but they often defend themselves by attacking the other person’s expertise.

Because of their problem with feedback, opportunists, diplomats and experts often struggle as leaders. In my experience, leaders must see themselves through the eyes of those they wish to lead. Cook-Greuter found that over 50% of adults have the mindset of an opportunist, diplomat or expert[2]. If half of us struggle in accepting feedback, is it any wonder that there is a shortage of effective leadership?

Bottom line: If you have a problem with feedback, you will struggle as a leader. Shift from seeing feedback as a problem to seeing feedback as a gift.

I am optimistic that anyone with a passion for leadership can develop the purpose necessary to accept feedback. Anyone who wants to help people can develop the norm that feedback is acceptable. Anyone who wants to be the best leader possible can become an expert in seeking and using feedback.

Changing your view of feedback is not easy. It requires substantial growth and development, possibly even a fundamental shift in your world view. Reflection, coaching and practice may help you open yourself to negative feedback. Reflection, such as a journaling, meditation or quiet time, can help you examine yourself and shape your impact as a leader. Leadership coaching helps you create a plan to improve your feedback skills and hold yourself accountable to put that plan in action. Like any other competence, practice accepting feedback is necessary. You need to find the right situations to practice receiving negative feedback. You may want to start in a safe and supportive environment, such as with your coach or in a training class. Then, practice with your trusted circle of advisors in your work situation. Soon, you will want to practice requesting feedback from a wider circle – including people whose expertise or motives are not always clear. Feedback from the bozos and politicians is a gift, because their perspective impacts your leadership as much or more than your circle of trusted advisors.

The problem with feedback is our unwillingness to receive negative feedback. The solution is simple but difficult: See feedback as a gift. If you solve the problem with feedback, if you tackle this simple but difficult change, you will become a better leader and lead a richer life.

[1] This table is adapted from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004) “Making the case for a developmental perspective,” Industrial and Commercial Training, 36, 275-281.

[2] Data from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004), p. 279.

The Leader’s Tipping Point

By Allen Slade

Leadership is about creating sustainable performance in your team. Jim Clawson points out that effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a post on The Tipping Point of Performance, I talked about managing energy in others to create sustainable performance. As a leader, you have a proven track record of results. You combine competence, capacity and committent to success, so people are willing to follow you. But is your performance sustainable?

Bottom line: As a leader, you have to manage your own energy. Know your performance curve, watch for signs of an impending performance crisis and take dramatic action as needed.

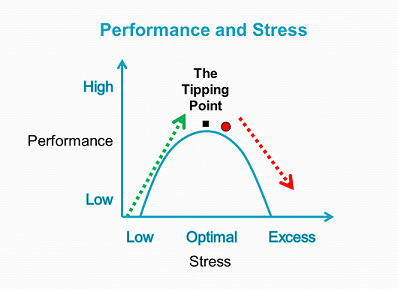

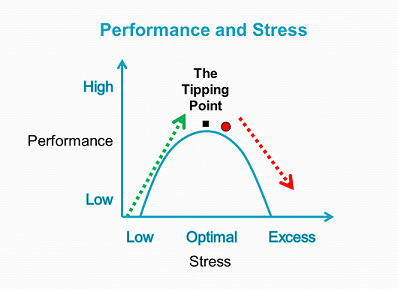

The performance curve is just as true for you as it is for the people you lead. We all experience this inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between your level of stress and your performance holds, but only in the green zone.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

Bottom line: Push youself, but know your own tipping point. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Manage your own stress wisely, especially on the dangerous part of the performance curve.

Stress reduction strategies. Whether you are at the top of the green zone or at the tipping point, try stress management strategies. Simplify your life. Practice centering. Off load non-essential work. Get help from your boss, in terms of more people, more resources or more time. Ask your colleagues for support. Delegate to your team.

Develop yourself. Long-term, grow your capacity for performance to avoid a stress-induced performance crisis. Develop new skills. Practice skills to the point of mastery. Practice for speed, not just completion. If you can write methodically, practice writing under a deadline. (Blogging three times a week is speeding up my writing!) Coaching can help, whether you are an executive, leader or golfer. At Slade & Associates, we coach executives and leaders to maximize their performance. There are certain things we don’t do, so you would do well to find your own golf coach.

Your urgency in reducing your stress depends on your position on the performance curve:

Top of the green zone. If you push harder but don’t see much improvement, you may be approaching the top of your green zone. Be careful, because you could hit your tipping point. Be alert for further stress, and consider strategies to reduce stressors or increase your performance capacity.

The tipping point. Approaching your tipping zone is dangerous. If familiar tasks become harder, if your inbox is overwhelming, if you snap at reasonable requests or if you work longer with fewer results, you may be at your tipping point. At the tipping point, you still have time. You can think. You can experiment with one stress reducer at a time. Take action now to reduce your stress. Climb back down into the green zone while you can still think clearly.

The red zone. Passing your tipping point is catastrophic because of the accelerating downward spiral of performance. To get out of the red zone, aggressively implement stress management strategies. Make a plan that combines at least two or three big stress reducers – simplify, center, get support from your boss, delegate, etc. Make smart requests ask your boss for support or delegate. Whatever the details, take dramatic action. In the red zone, you must act now.

A lifeguard. I must confess: This red zone advice may not work. The downward spiral of performance undermines your decision making and behavioral flexibility. If you are drowning, sometimes you can’t save yourself. You need a lifeguard who will know you need help and step in during a crisis. Your lifeguard could be a friend, a mentor, a coach or your family. Before a red zone crisis, build strong relationships. Be transparent, accountable and open to constructive feedback. Then, if you are drowning in stress, you will have someone willing to dive in to save you.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for yourself and for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

The Tipping Point of Performance

Allen Slade

I love sports movies, especially about underdogs. The critical moment is when the coach or loved one gets the underdog fired up. I love Rocky II, when Talia Shire lights Rocky’s fuse from her hospital bed and Remember the Titans, when Denzel Washington gives a moving call for unity in the Gettysburg cemetery.

As a leader, do you try to fire up your team? Be careful. If you play with fire, you can get burned.

Clearly, there are times when you need to establish a sense of urgency. But asking for extraordinary effort can backfire. As the performance curve below shows, there is an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between stress and performance does hold, but only in the green zone.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

The problem hits at the top of the curve. When a person reaches the tipping point, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance leads to a downward spiral in the red zone. People become anxious. They act indecisively, work slower or make more mistakes. As their performance decreases, their anxiety increases, further decreasing their performance. Notice the red marble at the top of the performance curve. In the red zone, the marble accelerates down the curve of poor performance. As a leader, if you push a person too far, their performance drops. And, their performance will continue to get worse because of the downward spiral.

Bottom line: Push for performance, but avoid the tipping point for stress. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Aim for high performance, not peak performance. I coach leaders to avoid pushing people to their tipping point. If the tipping point is at 100% performance, aim for 90 or 95%. Then, your team member has a stress buffer. If there is a coffee spill that wipes critical data or a car wreck going to the big meeting, they will have the psychological reserves to get through it. If you push to get the full 100%, your people may tip into the red zone.

Develop your people. If you wish to increase performance, but a person is near the tipping point, think development first, motivation later. Increase their competence and capacity, so they can perform better while maintaining an essential stress buffer.

Be a lifeguard. Your people can drown in stress. The downward spiral of performance undermines decision making and behavioral flexibility. If someone is in the red zone, you may need be their lifeguard. Watch for signs of stress in your team members, watching for people at the tipping point or in the red zone. Then, throw them a life line. Offer more resources, renegotiate deadlines, offer them time off to refresh and rest. Be creative – think of the rousing speech that fires up the underdog, then do the opposite.

Know your team. Everyone is different. The people you lead have different capabilities and stress tolerances. They will show different warning signs of a stress-induced performance crisis. Get to know your people before a crisis. Have regular dialogue with every team member. Seek insight about their performance patterns, personal stressors and individual signs of overload. This will equip you to be a stress lifeguard.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.