When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Leadership Tools: Purpose and Passion, Feedback and Subtlety

Allen Slade

The most effective leaders adapt to the situation, but they are driven by their own purpose and passion. You can stumble by being inflexible. You can stumble if circumstances drive you. The best leader will balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose.

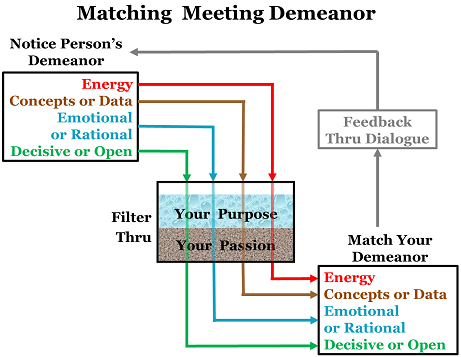

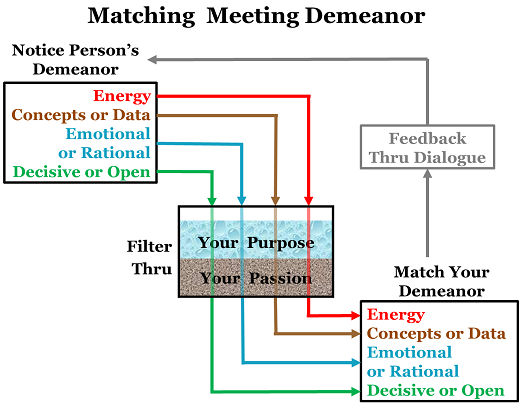

How do you balance adaptability with purpose and passion? One example is the leadership tool of matching meeting demeanor.

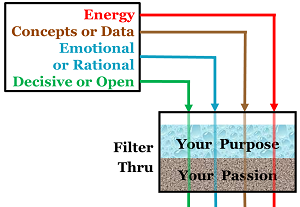

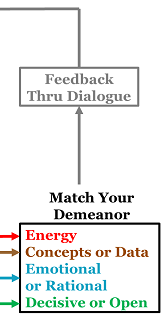

As you match the four aspects of meeting demeanor (energy, concepts or data, emotional or rational persuasion, decisive or open-ended), you need purpose and passion, feedback and subtlety.

Purpose and Passion

As a leader, your purpose sets your direction. Your passion energizes your actions. Your purpose and passion should filter everything you do, including your meeting demeanor.

As a leader, your purpose sets your direction. Your passion energizes your actions. Your purpose and passion should filter everything you do, including your meeting demeanor.

In a meeting at Microsoft, a vice president, my boss and I were synced up on meeting demeanor. We had medium energy and we were looking at concepts, rationally and decisively. Then, we discussed “what would happen if” we were asked to violate employee confidentiality. Because of my passion for confidentiality, I immediately switched demeanor. I went high energy and made an emotional argument. In other words, I threatened to quit. The meeting quickly broke up, my boss high-tailed it down the hall and I was left standing outside the VP’s office.

The VP apologized the next morning, and I was never asked to compromise my standards. But, even if I had lost my job over this outburst, my passion for confidentiality is so strong that I would have been content with my actions.

Feedback

Leaders have to balance constancy of purpose with openness to feedback. To be effective, you need feedback on your impact.

If you have no awareness of others’ meeting demeanor, you will usually not be very effective. If you take a quick snapshot of energy, data vs. concepts etc., at the beginning of the meeting, you will be more effective.

If you have no awareness of others’ meeting demeanor, you will usually not be very effective. If you take a quick snapshot of energy, data vs. concepts etc., at the beginning of the meeting, you will be more effective.

But, just like video is richer than still photos, you want to have continuous feedback on your meeting impact. Watch their body language, voice tone, and what they say to see if you are truly matching up your demeanor.

Match, Don’t Mimic

The wise leader will adjust meeting demeanor directionally to fit the demeanor of others, but not to excess. I suggest matching at a level of 80% to 120%.

- If the other person has much higher energy than you, adjust your energy to 80% of theirs. If they are much lower energy, adjust your energy to 120% of their energy.

- If they are all about concepts, don’t skip the data slides in your presentation. Just touch them lightly and move on.

- If they are absolutely decisive, match their drive to decide, but reserve the right to request a future meeting to follow up on the issue. If you request followup decisively, they are likely to say yes.

Bottom line: Your impact is magnified by matching the meeting demeanor of others in the room. Filter your actions through your purpose and passion. Get instant feedback by observing how your demeanor is impacting the others. And be subtle – match demeanor, don’t just mimic behavior. Then, your meeting influence will grow as the people around you respect your adaptable leadership.

Leadership Tools: Matching Meeting Demeanor

Allen Slade

Leaders need a toolbox full of tools for task leadership (budgeting, scheduling, goal setting, task execution) and relationship building(communication, decision making techniques, empathy). To use these leadership tools well, you need to diagnose the situation before you pick your tool.

A coaching client asked me “How should I act?” in an important meeting. I suggested matching his confidence to his competence and matching his demeanor to the other person. Let’s look at how “demeanor matching” works.

Often, leaders are called upon to persuade someone to take action. You might be planning with your boss, problem solving with an employee, trying to close a sale or interviewing for a job. It’s important to focus on the content of the meeting, but your influence will be determined by the tone of the meeting. How do you get your demeanor right?

Consider four dimension of meeting demeanor:

- High energy vs. low energy.

- Concrete data vs. abstract concepts.

- Rational persuasion vs. emotional persuasion.

- Decisive choices vs. option multiplying.

If two people are badly mismatched on any of these dimensions, the meeting will not go well.

We have all been held hostage in meetings. The other person is not on your wavelength and they are clueless about their lack of influence. They are high energy while you are drifting off. Maybe they offer abstract concepts when you need hard data. Or they make an emotional appeal when you want a rational argument. They push for decisive action when you want to keep your options open.

To avoid holding others hostage in a pointless meeting, don’t be tone deaf. Start by noticing the other person’s demeanor, then decide how your meeting demeanor needs to adjust.

Energy. If they have little energy for this topic, don’t try to bulldoze them. Take a low key approach. Pause, contemplate, listen even more than usual. But if they have high energy, ramp up your excitement to match.

If your purpose is to pursuade them, you may have to go against your native personality. Extroverts may have to calm down. Introverts may need to get fired up.

Concepts/data. If their conversation centers around concepts, principles, precedents, fairness – respond in kind. If they ask for data, proof, evidence, case studies, give them the numbers and facts they need.

Once again, you may be more conceptual or more data oriented, but don’t let that undermine your effectiveness if the other person is on a different wavelength.

Emotional arguments or rational arguments. Listen and observe. If they say or act in a way that suggests they want to approach this topic through an emotional lens, paint your argument with the colors of feeling. If they want to argue, respond with logic.

The “emotional intelligence” industry is built on the failings of leaders who think it is irrational to be emotional. You can also fail with feelings when the other person wants logic. Either way, if your purpose is to persuade, you may have to step outside your native logic to match their meeting demeanor.

Decisive or open. Sometimes, the other person wants to decide now. Other times, they want more options, more evidence or more people involved.

If you are naturally decisive but they want more time, you may need to practice patience. If you tend to keep your options open but the other person expresses impatience, you may need to work toward a “best guess” decision.

Bottom line: Effective leaders are versatile in their meeting demeanor. They use high energy or calmness, concepts or data, feelings or logic, decisiveness or patience, as needed to fulfill their purpose in the meeting.

In your next meeting, try noticing the demeanor of the other person. Then notice your own demeanor. Adjust as needed to be at your most influential.

Leadership Tools: Confidence

Allen Slade

Effective leadership requires adaptability. Leaders should fill their leadership toolbox and then pick the right tool for the situation. In other words, match your behavior to the task at hand.

Last week, a coaching client preparing for a one-on-one meeting asked “How should I act?” Because principles of leadership are outdated, I didn’t give a one-size fits all answer. Instead, I suggested two ways to match his behavior to the situation: Match your confidence to your competence (today’s topic). Your demeanor should match the other person’s demeanor (in the next post).

As a leader, your confidence is a tool. You should be able to influence others based on your experience, your expertise or your position of authority. But like any tool, you can misuse your confidence.

Overconfidence is a common leadership failing. If you choose to act confident, make sure you have the competence to back it up. If all you own is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If your leadership “style” is always high confidence, you will hammer decisions and people. Don’t be that leader.

Lack of confidence is another leadership failing. If you act like you do not know, you will undermine your leadership. If you don’t act like a confident leader, no one will want to follow you.

Even moderate confidence has drawbacks. “Powerful but approachable” or “humble yet decisive” may be desirable blends, but there are times when very high confidence (or very high humility) would be better than a compromise.

Sticking with one level of confidence – high, low or in between – would be leading on cruise control. Instead, match your confidence to your competence.

Suppose you face a high stakes technical decision. How can you match your confidence to your competence?

If you are a novice in the technology, listen and learn. Ironically, you can build credibility by complying with others. Save your confidence for situations where you know what you are talking about.

If you know about as much as the others in the room, engage in a good give and take. Bring your competence to bear, but don’t be overbearing. Admit the limits of your expertise and experience. Value the competence of others.

If you are highly competent to deal with this issue, you can show analytical strength and make hard-hitting recommendations. But even as the most competent person in the room, treat your confidence as a tool rather than a trait. At times, put confidence back in the toolbox to pull out other tools like listening or consensus building.

Bottom line: Treat confidence like a tool rather than a trait. Match your confidence to the situation to maxmize your credibility and influence.

Using the Tools of Leadership

Allen Slade

As a leader, it is not enough to have the job title. At the point of action, you need to choose the right tool for the job.

Leaders can’t operate on cruise control. Instead, they should will fill their leadership toolbox with a variety of tools: Task and person leadership. A variety of communication techniques. A range of decision making approaches. Verbal, quantitative and emotional intelligence. Macro and micro perspective. Fast or slow action. Problem solving and paradox managing.

But you can mess up, even with a full toolbox. At the point of choice, you need to know which leadership tool to pick up. If you pick up a circular saw to cut hard to reach nails, don’t expect it to go well.

But you can mess up, even with a full toolbox. At the point of choice, you need to know which leadership tool to pick up. If you pick up a circular saw to cut hard to reach nails, don’t expect it to go well.

There is no simple how-to guide for leadership. While Amazon lists 86,941 books on leadership (and probably more by the time you read this post), be careful. The reality you face is more complex and subtle than obeying leadership laws or imitating newsworthy leaders.

Bottom line: You need to develop your own leadership insight through experience and the wisdom of others.

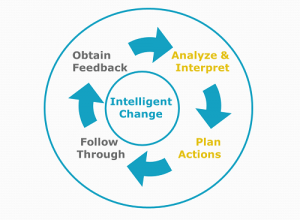

Leadership insight starts with personal experience. As you develop the ability to use a leadership tool, you will start to develop a sense of when that tool is the best choice. Maximize your growth by taking an intelligent change approach to your leadership experience.

Risk-taking. Leadership insight starts with action – what’s called follow through in our intelligent change model. Excessive perfectionism will keep your shiny new tool in the box.

Risk-taking. Leadership insight starts with action – what’s called follow through in our intelligent change model. Excessive perfectionism will keep your shiny new tool in the box.

Feedback. Experience-based learning happens only with feedback. You need to know how the tool worked to know when to use it.

Reflection. It is not enough to experiment and to collect feedback. You must analyze and interpret your experience. Contemplating the what, how and (especially) the when of your successes and failures will help you figure out when to choose a leadership tool. To be accountable for reflecting on your leadership, try keeping a leadership journal or chat with your circle of trusted advisers on a regular basis.

The wisdom of others. You learn faster with help. Teachers, mentors and coaches are all valuable resources to help you figure out your personal theory of leadership. As leaders mature, they learn less from the expertise of teachers or the experience of mentors. From mid-career on, leadership growth requires finding your own leadership coach or executive coach. Ask your senior leader or HR person if your company can provide a coach for you.

Fill your leadership toolbox and develop your insight so you know what works. Then, you will be ready to grab the right tool for the situation.

The Leader’s Toolbox

Allen Slade

Before rebuilding our friends’ deck, I loaded my van with tools: 3 power saws, 4 drills, 3 measuring squares and a bucket full of hand tools. Why so many tools? Wouldn’t one saw be enough? The circular saw cuts fast and straight, but isn’t maneuverable. The sabre saw cuts straight or curved, but slow. The reciprocating saw is for demolition – maneuverable but leaves a jagged cut. The third measuring square was unnecessary, but every other tool was used repeatedly.

In Leading on Cruise Control, I suggested that the best leaders adjust to the conditions they face. As a leader, you need a variety of leadership tools and the ability to diagnose what tool is needed for the situation at hand. But tools come before diagnostic skill. If all you own is a hammer, then everything looks like a nail. Here is a partial list of tools that should be in every leader’s toolbox.

Task and Person Leadership. The ability to focus on task leadership – resource allocation, project management, goal setting and execution. And, the ability to build strong and mutually beneficial relationships.

Communication. One-on-one, small group and large group. Rhetorical persuasion, information sharing, story telling and listening. Requests, offers, negotiations, declarations and assessments. Management by walking around and the ability to influence from a distance.

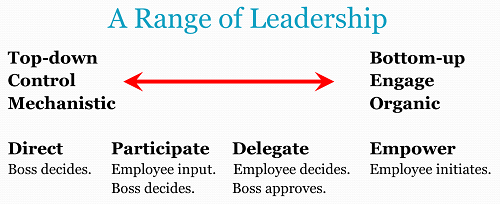

Decision Making. Data-driven or political decisions. Optimizing or satisficing. The full range of employee involvement – Direction, participation, delegation or empowerment.

Fast and Slow. Strategic thinking and instinctive reaction. The ability to do exhaustive, multi-disciplinary long-range planning and the ability to leap before you look.

Intelligence. Verbal, quantitative and emotional intelligence. The ability to see the big picture and to edit the pixels. The ability to solve problems and to manage paradoxes. Principled moderation.

How do you add tools? Start treating every day as a leadership laboratory. Do many mini-experiements and get lots of feedback. Take every opportunity to try the new and different. Communicate differently – new groups, new approaches, new technology. Take every class you can.

Longer term, take on big challenges. Get another degree. Take on stretch assignments. Switch functions. Switch careers. Cross cultures.

For an emerging leader, this list can be overwhelming. Be patient. It takes time to fill your toolbox.

For an emerging leader, this list can be overwhelming. Be patient. It takes time to fill your toolbox.

For a senior leader, you have many of these tools already. Don’t be satisfied. For the deck project, I could use a miter saw for the trim. Keep adding leadership tools.

How full is your leader’s toolbox? Don’t try to lead with duct tape and a pair of vice grips. Get the tools to do the job right.

Leading on Cruise Control

Allen Slade

One of the great conveniences of driving is cruise control. You can take your foot off the gas pedal and the car maintains speed. I recently drove 400 miles in a car without cruise control – in the rain, after a long day – and I was miserable.

For leaders, cruise control is also handy. You develop a leadership style that works. You build on past success. You lead with policies, procedures and patterns. You can drive the organization with relative ease, even in the rain after a long day.

There is a minor problem with leading on cruise control. You will not lead very well. As Skinner and Sasser conclude:

Managers who consistently accomplish a lot are notably inconsistent in their manner of attacking problems. They continually change their focus, their priorities, their behavior patterns with superiors and subordinates, and indeed, their own “executive styles.” In contrast, managers who consistently accomplish little are usually predictably constant in what they concentrate on and how they go at their work. Consistency . . . is indeed the hobgoblin of small and inconsequential accomplishment.

The best leaders, like the best drivers, adjust to the conditions they face. They know faster change is their only advantage, and they go slow to go fast. The best leaders can give the rousing speech, they can hold the quiet conversation and they can listen. The best leaders shift decision styles. They use the full range of leadership: direction, participation, delegation or empowerment.

Bottom line: The best leaders do not lead on cruise control. They adjust their leadership to the needs of the moment. They are versatile. They are inconsistent in order to gain consistently great results.

How versatile are you as a leader? Do you need a greater range of speed and style? Two suggestions:

Create a leadership scorecard to unlock your habits with data and reprogram your behavior.

Find out if your organization will provide you a leadership coach or an executive coach to help you identify opportunities to increase your flexibility.

Permanently disable your leadership cruise control. Lead according to the situation. It may be less comfortable, but you will be a better leader.

Managing Negative Deviance vs. Leading with Appreciation

Allen Slade

In our culture, pragmatism runs deep. We see through the lens of problem solving. We look for negative deviance by measuring performance against standards and focusing on shortcomings. We identify weaknesses and we punish shortfalls. We hold others accountable to meet standards. If someone does not measure up, we take corrective action. If someone does meet one set of standards, we look for other areas where they have fallen short.

Yet, as a leader, you are responsible for the debris field of negative deviance. Too much control, too much problem solving undermines your team’s engagement. If you are always focused on problems, your team will lose energy. As I said in The Problem with Problem Solving:

If a given task or situation seems to be laden with problems, you lose energy for that task or situation. External factors (such as a paycheck) may cause you to continue with that relationship, task or situation, but your heart won’t be in it. Excessive problem solving is the problem.

If problem solving drains energy, appreciation builds energy. You must be able to appreciate people and opportunities. You must be able to recognize what is good, true, effective and beautiful. You must reward progress, not just punish shortfalls.

As a leader, what can you do to help your team maintain the right balance between problem solving and appreciation?

One buffer to negative deviance is leading with appreciation. As a leader, you should look for what is good, true, beautiful and effective. You must help your team members leverage their strengths, not just fix their weaknesses.

I encourage you to try powerful questions to lead with appreciation. The right questions can help shift your team’s focus from problem solving to building on what works well. Pull out the positive by asking:

What is going well? What is better than expected?

What are we doing right?

How are we better than the competition?

Where have we improved? What have we learned?

How can we build on our strengths?

Leading with appreciation will help shake your team out of persistent problem solving. Your team will discover best practices and build on existing knowledge. As your team gets better at appreciation, they will discover sustainable success.

You will also see an impact on your team’s energy. People will engage because they are involved in success, not just a series of problems.

As a leader, your job is to manage energy in others. Try less management of negative deviance and more leadership with appreciation. Then stand back and enjoy the sustained power surge.

Test Your Ejection Seat

Allen Slade

Felix Baumgartner’s space jump had a dramatic buildup to a truly amazing physical feat. The video of Baumgartner spinning and tumbling at 700 m.p.h. is heart wrenching. And it ended with a perfect landing.

However, the “mission” was presented as a NASA-like experiment to make space jumping viable for escaping from a space vehicle. The mission was not very NASA-like. The flight director was no Chris Craft. And Baumgartner is an extreme athlete, not an astronaut. His poor checklist discipline and his concern with styling his hair after removing his helmet was more Tom Cruise than Alan Shepherd.

My father, Harry Slade, worked at NACA/NASA from the beginning of the jet age through the space shuttle. And, in 1976, in the New Mexico desert, he helped test one of the oddest emergency systems in the world: a helicopter ejection seat. How does Baumgartner’s space jump compare to a helicopter ejection seat?

The best ejection seats are virtually automatic – pull one lever and hang on. Baumgartner’s exit was slow and difficult: a long checklist and keeping his cool while tumbling at 700 m.p.h. But Baumgartner did not jump from a hypersonic spacecraft. He bunny hopped from a capsule floating gently beneath a balloon.

Space jumping will require more planning and testing before it provides real safety. In an emergency space jump, the craft would probably be spinning, disintegrating or on fire. A Baumgartner-like jump would be too complex and too physically stressful for a space tourist to survive.

NASA’s helicopter ejection seat was not like the space jump. The ejection seat was for a helicopter testing next generation rotor blades. Test rotors were thinner and lighter, increasing the risk of failure. Rotors are most likely to fail during takeoff and landing. A pilot could not eject down because of the low altitude. The pilot cold not eject sideways either, because rotor debris would be spiraling to every point of the compass. The ejection seat had to go up, through the path of the rotors. The ejection sequence was complex: pull the ejection handle, blow off the rotors with explosive bolts, blow the hatch, eject the seat, cut the seatbelts, then deploy the parachute. Asking a pilot to remember these steps during a crash was a recipe for failure. The pilot’s only job was to pull the ejection handle and let the automatic system do the rest.

For leaders, when the crisis happens, it is usually too late to build an ejection seat. When time and tempers are short, people go into survival mode. The brain shuts down cognitive processes, attention narrows and choices seem limited to fight or flight. What backup plans do you need to create? Your leadership crisis may be the loss of a key employee, an unexpected customer request, failure of essential equipment or overload of a critical operation. If the crisis happens quickly, you need to already have an ejection seat.

For a job interview in 2002, I made a presentation on leadership. I emailed my presentation to the host. By plan, I arrived 15 minutes early to check the room. When we turned everything on, my presentation was not on the laptop and my host did not know how to transfer the file. (It was 2002.) No problem – I had a floppy disk. (No USB in 2002.) She found an external disk drive, but the drive did not work. No problem – I had transparencies. They found a dusty overhead projector. When we turned it on, the bulb did not work. No problem – I activated the built in back up bulb. The second bulb worked. I tested the projected image, focused the projector, focused my emotions and was ready to go. (I had one more backup if the second bulb blew – use the whiteboard.) The presentation went well, and I was offered the job.

Lesson #1: For critical activities, have multiple backup plans before the crisis.

The helicopter ejection seat offers another lesson. My dad was in New Mexico to test the seat. The helicopter was bolted to a jet sled, accelerated to flight speed, then a test dummy was ejected. The first test was almost right. The rotors did not blow off before the seat was ejected, shredding the test dummy. (A watching test pilot walked away saying “I’m never flying that bird.”) The NASA team found and fixed the flaw in the timing circuits. All the other tests were successful.

When I joined Microsoft in 1999, my key task was to make the employee opinion survey a success. The 1998 survey locked up because of overloaded servers at the survey host. Under my direction, we created backup plans for every problem we could imagine. More importantly, we tested our back up plans. We did load testing, usability testing, data integrity testing and translation testing. We even tested our testing. In effect, we accelerated the survey to flight speed and pulled the ejection handle. The testing identified problems that we fixed, then we tested to the point of repeated perfection. The actual survey went well – on time, with virtually 100% uptime.

Lesson #2: For critical activities, test your backup plans before the crisis. Make the tests as realistic as possible. And test your tests.

As a leader, what are your key processes? How can they fail? What are your plans for overcoming failure? And how well tested are those plans?

Don’t rely on extreme leadership ability in a crisis. Few of us can tumble at supersonic speed like Felix Baumgartner. Plan for failure and test your plans until you know your ejection seat will save the day.

Leading in Stormy Weather

Ben Slade

In the early 1980s, the Bell Telephone Company was convicted of antitrust violations and broken up into several “Baby Bells.” Frequent reorganizations, constant rumors, and a lack of job security took a toll on the workforce. Many employees were overwhelmed by the stress. They experienced physical, mental, and emotional strain at work and at home. However, some employees emerged from the deregulation with an increased sense of energy and vitality. These hardy survivors proceeded to make meaningful contributions both inside the company and out. What distinguished the overachievers from the overwhelmed?

Prolonged or intense stress can put employees at increased risk of illness, marital problems, and reduced productivity. However, some individuals emerge from very stressful events relatively unscathed. Understanding stress vulnerability can help identify opportunities to create pathways to resilience.

One pathway to stress resilience is hardiness. Hardiness has three components: commitment, control, and challenge. Hardy individuals are committed to their organization, finding meaning and stimulation from the work that they do. They believe they can exert control on the world around them, and that their fate is not predetermined. Finally, they interpret difficult experiences as challenges that lead to growth and maturity, and are willing to persist in a difficult environment rather than flee for temporary comfort.

If you are a hardy leader, you will typically excel in stressful circumstances. Although you can sometimes reshape your environment to reduce this stress, you are often surrounded by challenges that are difficult or impossible to change. Your own responses will probably not change the technological limitations, economic recessions, or government regulations that boost your stress levels.

Hardiness is like a rain jacket, deflecting the rain without changing the intensity of the storm. You may not be able to control the environment, but a predisposition towards positive thinking and action can protect you from getting wet. By reframing hard times as an opportunity to excel and conquer, you actually boost your own resistance to stress.

As a leader, your hardiness may even be an umbrella for your team. This hardy leader influence is driven by social sense-making. You can increase your team’s stress resistance with your own behaviors and attitudes.

Transformational leaders inspire and motivate their followers by reframing obstacles as opportunities. Often, you cannot eliminate stress in the workplace. Instead, you can reinterpret stressful circumstances as opportunities to excel. Emotions which can interfere with performance (such as anxiety) can be translated into excitement. When you motivate your team to commit to achievable goals, help them believe that they control their own destiny and demonstrate how obstacles are challenges instead of threats, you have extended your umbrella of hardiness. You bolster individual resilience and improve organizational performance in the face of uncertainty and change.

Do you interpret events in a hardy manner? Do you convey the right messages to your subordinates in the face of uncertainty? You can’t avoid the storms of change, but you can use commitment, control and challenge to help you and your team stay dry.

What to Expect from Leadership Coaching

Allen Slade

Gifts can be a source of joy or a nasty surprise. If your company provides you a leadership coach, how should you react? Heartfelt delight or muted disappointment? Is leadership coaching the perfect gift for you? Or is it the ugly sweater?

Leadership coaching is a powerful gift when it works as designed. Coaching increases your ability to achieve results and build healthy relationships. It helps you stretch into your best self as a leader.

A talented and wise coach (preferably accredited) will help you stretch into your best self. The coaching conversation can be the high point of your week. Your coach’s insightful listening and powerful questions can trigger new insights into your leadership. The best coaches assume that you are the expert on your own situation. Your coach will draw out your expertise through inquiry, curiosity and gentle challenges. The mini-experiments you design together can lead to breakthroughs in your influence and your presence as a leader.

Leadership coaching comes in different flavors:

Coaching for achievement maximizes your performance in your current role. The leader wants to move from good to great. Your leadership coach will help you focus on the behaviors and thinking necessary to supercharge performance. For achievement coaching to have maximum value, you need to have already learned the ropes. That means 6 months or more in your current job.

Coaching in transition helps you adjust to a new role so you can have a fast start. Your coach will help you learn the ropes – making sense of your new role. Rapid sense-making will help you adjust your behavior, thinking and expectations to accelerate maximum performance in your new role. Transition coaching may start before, during, or soon after the leader has moved into a new role. Sometimes, recruiting firms will provide a leadership coach to ensure that the placement has the greatest odds of success.

Coaching in crisis is designed to turn around an unsuccessful situation. The leader’s performance is unacceptable in one or more ways, and the leader and the organization want to improve the situation. Successful crisis coaching requires the leader, HR and the leader’s manager to agree to have mutual candor, commitment to change and the expectation that things can improve.

When can the gift of coaching turn out to be an ugly sweater? One example is coaching in crisis when the organization has already decided to end the leader’s employment. Another example is when the leader’s confidentiality is violated.

Most ICF accredited coaches take steps to avoid these situations. If no turnaround is possible, Slade & Associates does not offer coaching in crisis. (However, if the leader’s employment is at an end, we gladly offer career coaching as part of outplacement packages.) We always require a written agreement of strict confidentiality. Our approach to leadership coaching safeguards our dialogue, maximizes your insight and drives intelligent change for your organization.

Leadership coaching is an incredible benefit. If your organization offers you a leadership coach, accept the gift gladly. Check on the coach’s credentials. Make sure your coach, your organization and you agree on the purpose of the coaching. Demand coaching confidentiality. Then, prepare to be surprised and delighted as you unwrap the insights and wisdom of leadership coaching.