When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Principles of Leadership Are Outdated

Allen Slade

When I teach leadership to business students, I often open the first class by asking students about leaders they respect. Mahatma Gandhi, George Patton, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Steve Jobs are often mentioned. Some students talk about their athletic coach or a former boss.

Then, we get to the heart of leadership. To save you the cost of tuition, here are the highpoints:

The “Great Man” theories of leadership don’t work.

There is no one best way to lead. The best way to lead depends on the situation.

The best leaders are not students of leadership.

There are no simple rules. I discourage imitating role models. I attack leadership trait theories. I undermine leadership style theories. Being the best leader you can be is difficult and complicated.

Those who look for simple answers are understandably disappointed.

Yet, there is a straightforward approach to leadership in my class. Be a student of followership and collect lots of data.

Be a student of followership. Don’t waste time studying leaders or leadership. Study the people you lead. The best leaders have incredible curiosity about the people around them. They ask people what’s important to them, then they think hard about the implications. They check for understanding by asking more questions. The best leaders shape their leadership behavior for their followers.

Collect lots of data. To understand people, the best leaders are hungry for information. They collect data with direct observation of the words, tone and emotions of others. They ask lots of questions. And they suck every bit of value out of any quantitative data they can get, through surveys, 360 reports, attrition data, customer data, etc.

For the visually oriented like me, here is how I capture this vision of leadership:

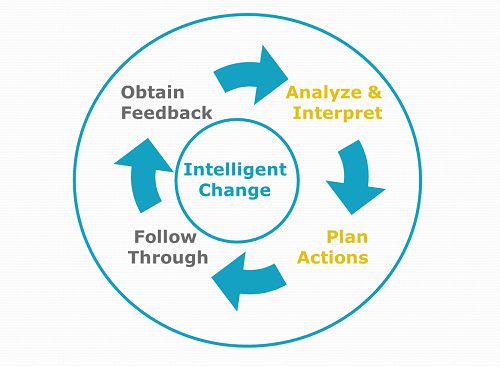

With a commitment to know the people you lead and a hunger for more data, you can bootstrap your leadership. You can create mini-experiments based on your tentative knowledge of people, and then correct your actions based on their feedback. You will develop a personal, flexible leadership style. And, I suspect, your impact as a leader will expand well beyond what you would achieve if you had simply tried to imitate the great leaders of the past.

Feedback Should be “Just Right”

Allen Slade

A careful reading of Goldilocks and the Three Bears suggests three lessons for leaders: Moderation in all things. Don’t be impulsive. Breaking & entering causes problems, especially at the Bears.

Previous posts have looked at The Problem with Feedback and Different Perspectives on Feedback. Today, we will consider moderation in two aspects of feedback. Instead of a single feedback cycle that may be too hot or too cold, just right feedback requires that you mix the timing of your feedback cycles. And, don’t just impulsively act on feedback. Use insight and analysis to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose.

Multiple Feedback Cycles

As a leader, you should be open to feedback because you need to know “When I walk in the room, who shows up for the other people?” You need to seek out feedback relentlessly.

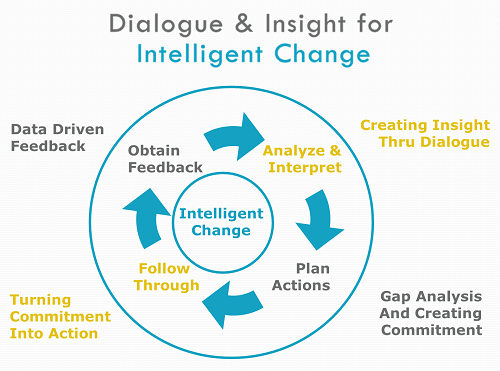

But it is not enough to collect feedback tidbits. To drive intelligent change, you must analyze and interpret the feedback you receive. You must plan actions based on the feedback. You must follow through with your plans. Then, you must start the cycle again by collecting more feedback. If things are going well, continue on. If your feedback suggest things are not going well, change something – your follow through, your action plan or your analysis and interpretation of the feedback. This feedback cycle drives intelligent change.

How long should your cycle take? Consider feedback cycles of three lengths:

Long-cycle feedback. This is feedback on long term impact, such as data from the annual employee opinion survey or a 360 report. Long-cycle feedback looks at the sum of your actions over a period of time. Long-cycle feedback is typically generated by the organization with safeguards to increase its validity (e.g., anonymity) and relevance to organizational leadership (e.g., a competency model). Yet long-cycle feedback by itself is not enough to develop your leadership. The assessments underlying long cycle feedback are complex and open to rating errors. And, a leader cannot afford to wait a year to find out if leadership changes are effective.

Short-cycle feedback. This is feedback on a recent event, such as post action feedback right after a meeting. Short-cycle feedback looks at your actions in the very recent past. The advantage of short-cycle feedback is that it reduces the delay in adjusting a new behavior. The disadvantages of short-cycle feedback are often a lack of anonymity and a lack of structure.

The quick check-in is a useful form of short-cycle feedback. After a conversation or meeting, ask “How did today’s conversation (or meeting) go for you?” Most of the time, the answer will be “It went well.“ or ”Great.” In that case, continue on. Sometimes, you will hear something of incredible value. “We are bogging down in the data.” “To be honest, I was bored.” “You have spinach between your teeth.” Treat this feedback as a valuable nugget. Adjust the agenda, amp up the excitement or do a quick floss job.

Instant feedback. This is feedback in the moment, such as watching non-verbal language of others in a meeting or hearing a change in voice tone during a phone call. Instant feedback allows the leader to adjust on the fly. Instant feedback requires mindfulness of the cues that others give in the moment. It also requires the ability to multi-task by talking and watching, by focusing on your message and your impact on the other party, at the same time.

You need a mixture of these cycles. Instant feedback and short-cycle feedback, in excess, may be too hot. Long-cycle feedback, by itself may be too cold. But, combined in the right proportions, these different cycles can be just right.

Balancing Openness to Feedback with Constancy of Purpose

When you receive feedback, another form of moderation is needed. You need to consider the feedback before acting. In the heat of the moment, while receiving negative feedback, you can go overboard. You can impulsively agree to do everything the feedback giver wants. This strong desire to please can backfire. If you submit totally to the other person’s judgment, you undermine the powerful dialogue that should come with feedback. And, you subordinate your purpose to their goals for you. In effect, you jump from feedback to action plan without your own careful analysis and interpretation.

It is better to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose. The other person’s feedback is always valid and always valuable. Yet their goals for you may not be identical to your purpose. My advice is to accept all feedback from all willing parties, without necessarily submitting to their action plans for you. The balanced reaction to feedback is to listen, to learn and to engage the other person in mutual problem solving.

Back at the Bears

Let me close with another observation: Goldilocks had no support team for her decisions. Impulse can be moderated by wise counsel. Mixing feedback cycles is more complex than simply waiting for annual leadership feedback. Balancing openness to feedback with constancy of purpose is harder than a simple rule for action. I recommend using the power of collaboration to maximize the power of feedback. Work with your circle of trusted advisors, your mentor or your leadership coach to master feedback. Gather a support team to create dialogue and insight to drive intelligent change for your leadership.

Bottom line: As a leader, actively seek feedback. Gather the right mix of long-cycle, short-cycle and instant feedback. Balance constancy of purpose with openness to feedback. Gather your support team to get your use of feedback just right.

And don’t break & enter, especially at the Bears.

Steps for Planned Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

A model for planned change can help you navigate your way through uncharted territory. There are a lot of different change models out there, and many of them are numbered. Here is a partial list:

As a change leader, should you use a change model? If so, which one?

The bottom line: Use a planned change model. As for which model, go with what works for you and know when to yield.

I generally recommend a planned change model for my clients. A model can help simplify a complex situation, provide a common language for discussing change in your organization and can focus attention to guide action. In other words, a planned change model gives insight for intelligent change.

There are differences in the number, sequence and timing of the steps, but these differences are not very important. Which planned change model you use is a matter of preference and politics. If your preference holds sway, use what works for you. If the powers that be insist on a different model, you can yield with a clear conscience. I have scars from arguing too hard for change models that were not in vogue. Almost any planned change model will help chart your course through the change.

John Kotter’s 8-step model for leading change works as well as any, so I use it often. Here are his eight steps:

1. Establish a sense of urgency. I recommend an analysis of the forces for change and the forces for stability. If the forces for change are not great enough, regroup and restart.

2. Form a powerful guiding coalition. Get the right people with sufficient knowledge, influence and commitment to guide the change. If you initiated change without the juice to make it happen, get the power brokers on board.

3. Create a vision. This should be a powerful, brief and memorable summary of the change – what is changing, why and how it affects us. A fuzzy vision will make the rest of the process harder.

4. Communicate the vision. Get the vision out there and get all parties to join the process. But don’t see communication as a “tell and sell” campaign. Engage in dialogue. Underscore the key points and get your employees’ feedback, insights and creativity. Change your plan early and often based on this dialogue.

5. Empower others to act on the vision. You can’t do it all. Bet on your people. Encourage them to act without your tight control. The vision for change sets the boundaries and general direction. Let others sweat the details.

6. Plan for and create short-term wins. Change is hard work. Change is especially hard in the middle, after the initial excitement has died down and before the final success is clear. Discouragement must be managed. Celebrate your team’s success early and often.

7. Consolidate improvements and produce still more change. Build on your success. Leverage your successes and learn from your failed experiments.

8. Institutionalize new approaches. Lock in the new way of doing things with congruent changes to your strategy, structure, systems and culture.

If this 8-step model resonates with you, use it. If not, look for another planned change model. A good road map provides insight for intelligent change.

Faster Change is Your Only Advantage

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

In my post on Making Sense of Change, I highlighted the need to devote energy to sense-making during seasons of change. As a leader, how long are your seasons of change? When will things get back to normal?

The rate of change is accelerating. Moore’s Law originally applied to transistors, but the pattern of exponential change affects every process and every corner of your organization. Everything is accelerating – bigger changes, more changes, at a faster pace. Even the pauses are disappearing. When you complete a major change, you are likely to move on to the next change.

Bottom line: Change is the new normal. And your only sustainable competitive advantage is your ability to change faster than the competition.

Your organization’s ability to survive depends on its reflex time. You will prosper as a leader if you are on the front edge of change. And your team needs to get on board with the new normal.

Let’s think through the commitments, competencies and capacities needed for faster change.

Commitment to change. Change is here to stay. Don’t waste energy complaining about the latest change or wishing for past stability. Embrace the change. Look forward to change. Jump into the next challenge.

As a leader in the midst of change, you help set the tone for your team. Be a cheerleader for change. Get others excited about the bright future.

Growing change competence. As change accelerates, you need to be better at change. Treat every change as an opportunity to master new skills. Look for new ways of doing things. Be the first to tackle the new challenge, play with the new system, apply the new concept or talk to the new person. Today’s change is practice for tomorrow.

As a leader, you need to develop your team’s change competence also. Coach them in change competence. Take risks with your team’s decision making – empower them to act without your tight control. Their growth today will make tomorrow’s change easier for both of you.

Capacity to change. It is not enough to be able to change. You need the capacity to change quickly and often. You have to multi-task competing changes. You must accelerate your sense-making so you can quickly climb out of the performance valley of change. And, you cannot rely exclusively on carefully planned change. You need to able to “ready, fire, aim” and just do something.

As a leader, you need to encourage your team’s capacity to change. Push your team to the point of change fatigue. Help them be quicker at sense-making. Get them to move beyond planned change so they can just do something. Then, their change muscles will have more capacity the next time.

You increase competence by mastering new skills. You increase capacity by using those new skills over and over again. I mastered the basic competence of riding a bike many years ago. I recently rode my first century. It was a major challenge to bike a hundred miles in one day. I needed commitment, competence and capacity. I had to commit to finishing the ride. I had to master newer cycling technology – a new road bike instead of my trusty old hybrid, shoes that lock into the pedals and sports drinks that taste like cold sweat. And, most importantly, I had to increase my capacity to go longer and faster by riding hundreds of miles before the actual century.

The demands of change are massive. Dialogue and rest can help you avoid be overwhelmed.

Dialogue. Surround yourself with people who support and encourage you in times of stress.

- Rely on your family members and close friends for encouragement. Talk about your changes. Talk about the impact on you physically, mentally and emotionally.

- Form a circle of trusted advisors with whom you can talk through the challenges and your change approach.

- Consider getting yourself a leadership coach.

Rest. Take a break from the relentless pace of change.

- As needed, stop and catch your breath. Consider using centering or some other activity to still your hands, quiet your mind and calm your heart.

- Schedule times of rest. Every Sunday, I take a sabbatical from work – largely avoiding email, Twitter and this website. I catch up on sleep that day and I think about the big picture. On Monday morning, I am ready to accelerate back onto the change expressway.

As a leader, you must also provide dialogue and rest for your team. If you are pushing them to the point of change fatigue, make sure they recover well. Support them in the midst of change. Talk about the change. Support them with advice. Thank them for their efforts. And, give some breathing room for them to recuperate.

Change is the new normal. The rate of change is accelerating. Your ability to change faster than the competition is your only sustainable competitive advantage. If you are overwhelmed by change, take a quick break right now. Then get a little help from your friends.

Making Sense of Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Can you perform at your maximum – can you give 100% – in the midst of change? Should you demand 100% from your team when they are facing change? Pushing hard for short term performance can undermine long term success and maximum growth. We need to leave breathing room for change to work its way out. We need to plan for a season of sense-making.

Meryl Louis defines sense-making as the psychological process of revising our cognitive map to figure out “what is new, different and – particularly – what was unanticipated.” Sense-making rewrites a large cognitive map:

- Understanding new duties, responsibilities, power structures, and peer relationships.

- Clarifying the new path to success, including new performance criteria and new goals.

- Developing new skills and behaviors to master the new role.

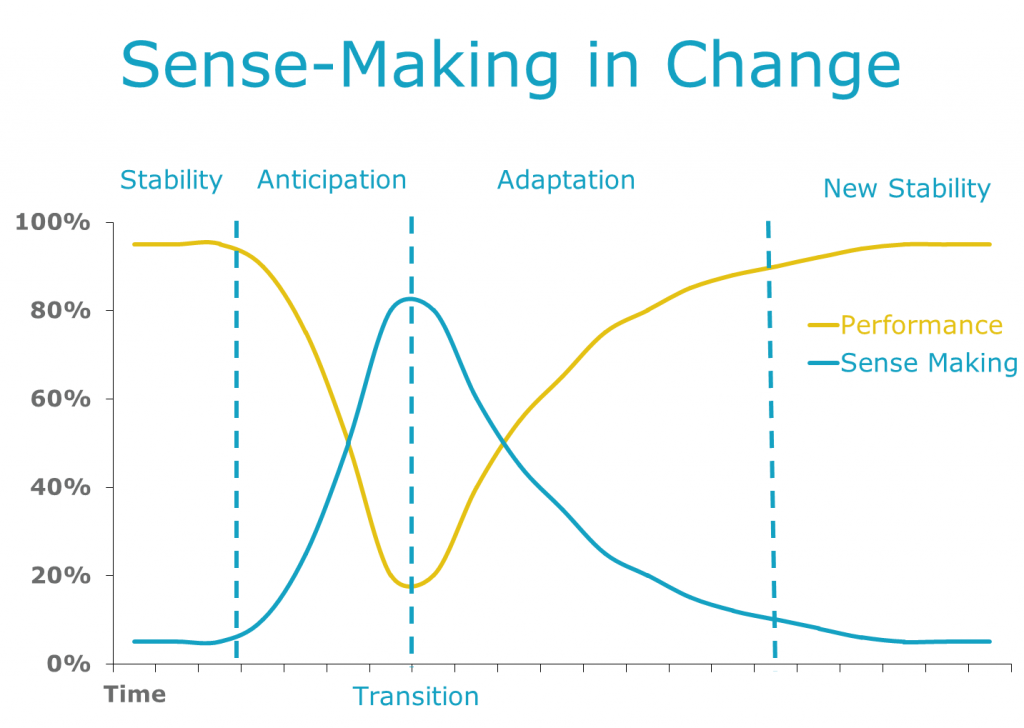

Here is a picture of sense-making in action:

When you go through a transition, you should expect a decline in performance. You will need to spend energy and time making sense of the new situation. In the midst of change, I ask my clients two questions:

How deep is your valley? The larger the transition, the deeper the expected decline in performance. A reorganization which just moves some boxes on the org chart will have little impact on your performance. A major change of systems, strategy, structure and culture will require more sense-making.

Where are you on the sense-making curve? The highest level of sense-making tends to occur at the point of transition. The hallway conversations linger longest the day the new strategy is announced. The job change is nested in farewell lunches and new employee orientation programs to give breathing space for sense-making.

When you lead others through change, you should plan for your team’s sense-making. This is tough when the change is triggered by competitive pressure. No matter what the performance demands, you can’t just wish away the need for sense-making. During the change, help your team through the valley. Give them perspective, just-in-time information and support to help move them to the other side.

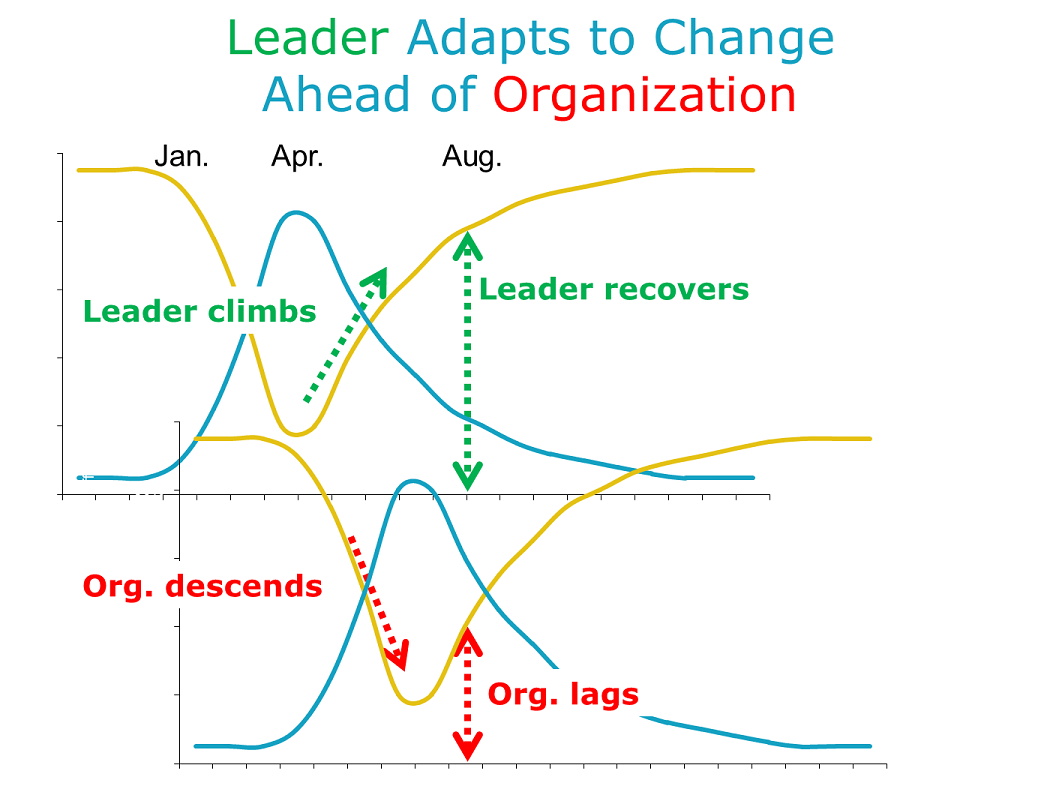

If change is rolled out top-down, the change leader will be further along the curve. You start planning a change in January and announce the change in April. You will be at the peak of sense-making and stress at the April announcement, but your organization is just starting the process. By August, your performance is almost back to pre-change levels, but your organization is just bottoming out.

This lag in sense-making can cause frustration and impatience. As a leader, you can falsely blame your team for not getting with the program. The reality is they need more time because they started the transition after you.

As a leader, plan for the season of change. Know where your people are. “How deep is their valley?” “Where are they on the sense-making curve?” Truly lead, not just in planning the tasks of change but also in making sense of the new future. Provide perspective, just-in-time information and breathing space to help them climb the far side of the sense-making valley.