When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

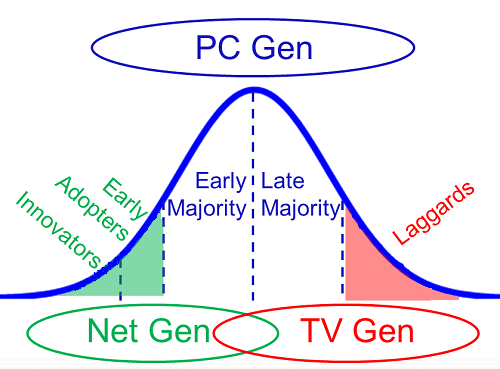

Leading Change for the Net Gen, PC Gen and TV Gen

Allen Slade

In a post on Digital Deception Detectors, I contrasted two views of technology:

The Net generation integrates technology fully with relationship. They adopt new technology for coolness, using Facebook (or Twitter or Pinterest or whatever) because their friends do. Using a network multiplies their friends on the network.

The PC generation sees technology as a tool. They master new technology to get things done. They aren’t early adopters. They won’t upgrade Windows or switch from email to Facebook without a good reason. They want a tested version of new technology, with no bugs and a good help function.

Here’s a third perspective:

The TV generation passively accepts what technology offers. They change the channel or dial the phone, but they allow other to create the channels and content. If technology does not work, they look for an expert or give up. They tend to be late adopters, mastering new technology under direction or duress. Once they have mastered a technology, they use it habitually.

Geoffery Moore categorizes people by how quickly they accept new technology – from early adopters to laggards.

The difference between Net, PC, and TV generations is not necessarily how quickly people adopt new technology. The difference is how and why people use technology. The Net gen asks “What’s cool? How can I connect to friends?” The PC gen asks “What works? How can I get stuff done?” The TV gen asks “What’s on tonight?”

As a change leader, how should you interact with the three generations?

The Net generation treats technology as a natural part of life. They can be the easiest to lead becasue they are are comfortable with technology change. However, they can be cynical about large organizations and their leaders. Their digital deception detectors are tuned for any sign of inauthenticity.

Microsoft’s old advertising slogan “Where do you want to go today?” worked well with the PC gen, but the Net gen’s reaction was “Riiight. Bill Gates, the richest man in the world, wants to help me accomplish my goals.” Trip their digital deception detector and you’ll lose the Net gen.

The PC generation has a utilitarian relationship with technology. They would rather not upgrade to the latest version of Office or change from email to Facebook unless there is a good reason. When getting their buy-in, leaders should focus on the great things they can do with the new system.

When we converted to a new web-based survey system at Ford Motor Company, our audience of executives and HR professionals were largely PC gen. Our key message: Better, Faster, Cheaper. We reduced turnaround time and costs, music to the ears of the PC gen.

The TV generation has a passive relation with technology, expecting to absorb what is transmitted. They can resist learning new technology that requires their active involvement. The TV gen may require a lot of persuasion, to the point of coercion.

One of my colleagues launched an executive information system restricted to vice presidents (no executive assistants allowed). One third of the vice presidents never logged on. They want their reports delivered to them, like turning on the television. The CEO decided to guide the non-users to leave the company as soon as possible. My colleague’s take “If you can’t change the people, sometimes you have to change the people.”

Bottom line: You can lead change across the generation gaps. For the Net gen, be authentic. Emphasize the coolness and connectivity of the technology without triggering their deception detectors. For the PC gen, focus on achieving business objectives. Be persuasive about the value of change. For the TV gen, confidently lead the change. This may mean directing the laggards to comply or leave.

Put it all together, and you will have authentic, goal driven and confident leadership of change. That’s the type of leadership all generations can get behind.

Coaching for the Long Hill of Change

Allen Slade

Last May, I rode my bike in a century. I had completed 50-mile rides before, but I had never ridden 100 miles in one day. I trained hard, but not hard enough. About mile 60, I boinked. My energy reserves were depleted, and my speed dropped five miles an hour. Halfway up a long hill, I stopped. I had to catch my breath and decide if I was going to finish. I completed the hundred miles, but it was a close thing.

Like the long distance cyclist, leaders must be internally motivated. External praise is rare. The cheers of the crowd are too distant to carry you up the hills. You cannot afford to boink at the 60 mile point.

There are signs of leadership fatigue everywhere. At a leadership conference last week, one of the keynote speakers suggested we give up trying to change large organizations. Several panelists talked about the loneliness of leadership.

Leadership lite is about prestige and power, personal glory and personal gain. Regular readers of this blog know that I do not prescribe leadership lite. In my experience, the challenges of true leadership are large. Change leaders must master the four C’s: commitment, competence, capacity and character. In general, change leaders have to work longer, harder and smarter than the people around them.

I don’t intend to discourage true leaders. You need to have realistic expectations of the leadership challenges you face. But you also need support. You probably will not find encouragement from the people you lead. You may not find support from your peers, especially if you are competing with them for budget, talent or promotions. And, if your own leaders are fully engaged, they may be more discouraged and stressed than you are.

There is hope. You are not condemned to a life of lonely leadership. You simply need to gather the support you need.

Use the support you already have. Reach out to your close friends and family. Engage your circle of trusted advisors. Talk about your challenges and your discouragement.

Once you become an executive, you probably should hire an executive coach for yourself. Even before then, if you are leading change, investigate whether your organization will provide a leadership coach. A good coach will provide real and present encouragement. A coach will also help you find the support you need in others. And, a coach will help you develop the commitment, competence, capacity and character you need to lead change.

Leading change requires you to climb the long hills without much encouragement. Get coaching so you can keep pedaling.

Compassion and Change

Allen Slade

Your character determines your impact as a leader in the midst of change. Character is one of the four C’s you need to master for change:

Commitment. Embrace the change. Jump into the next challenge.

Competence. Become better at change. Grow by tackling new challenges, playing with the new system, applying the new concept or talking to the new person.

Capacity. Be able to change quickly and often. Multi-task competing changes. Manage planned change, but also be able to “ready, fire, aim.”

Character. Be known for your integrity and compassion.

When I think about character, I see integrity as tough and compassion as gentle. Leaders clearly need to be tough to drive change. Your integrity should be rock solid, especially during tough transitions. To be known for integrity, you should be a truth teller and a promise keeper.

But how about compassion? How does this gentle character trait help your change leadership?

Change creates stress. It disrupts your followers’ sense of stability, causing them to feel adrift. Employees’ implicit understandings about job security, rewards, roles and responsibilities are shaken. Their relationships with top executives, you as a leader and even their peers can be destabilized.

One way to create stability during change is with compassion. Compassion begins with listening. If a change creates uncertainty, allow people to express their distress to you. Empathize with their feelings.

Next, be willing to act on their concerns. Provide real help. This means addressing their needs, whether it be for information, a bit of slack on deadlines or practical assistance in accomplishing their tasks.

Often, compassion requires personal sacrifice. To meet the needs of the people you lead, you have to devote extra time and energy to them. This is especially tough in times of transition, because you are also stressed. You need to be hardy enough to be a servant leader. You will need to give more – work longer, invest more emotionally, listen when you would rather talk.

Branding yourself as a servant is not just something for a job interview. I believe leaders are called to serve. Servant leadership is a high calling to a lowly state. The most extreme example of servant leadership is celebrated at Christmas:

In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant. (Eph. 2: 2-7).

As a leader in the midst of change, you need commitment and competence. You need capacity so that you can give more. Your character should combine integrity and compassion. Then, you can lead through the tough times and earn the proud title of servant.

Integrity and Change

Allen Slade

In Faster Change is Your Only Advantage, I wrote about three C’s you need to master for change:

Commitment. Embrace the change. Look forward to change. Jump into the next challenge.

Competence. Become better at change. Grow by tackling new challenges, playing with the new system, applying the new concept or talking to the new person.

Capacity. Be able to change quickly and often. Multi-task competing changes. Be able to manage carefully planned change, but also be able to “ready, fire, aim” without detailed plans.

These C’s are still important. But there is a fourth C:

Character. Be known for your integrity and compassion.

We will look at compassion in our next post. Today’s focus is the need for integrity in the midst of change.

Your integrity as a leader should be rock solid at all times, especially during tough transitions. To be known for integrity, you should be a truth teller and a promise keeper.

Truth tellers mean what they say and say what they mean. They avoid both active deception and passive deception.

Being a truth teller does not mean that you violate confidences. Sometimes, managers are privy to information that they cannot share with their team. For example, during a reorganization, employees may ask if their jobs are secure. If layoffs are possible, do not falsely reassure employees. But you also should not jump the gun. Instead, you may have to say “I don’t have any information to share with you at this time.”

Promise keepers make strong promises and keep them. Chalmers Brothers distinguishes three kinds of promises:

“Strong promises: Promises that I am absolutely committed to keeping. You can count on me.

“Shallow promises: These look like a strong promise, but what I don’t say out loud is ‘unless X or Y happens.’ . . . Here, we reserve a private ‘out’ for ourselves, but we don’t let the other person know.

“Criminal promises: These are promises that at the moment of making, we know we have no intention of keeping.”

A reputation for integrity requires making strong promises and keeping them. Then, people will know you are as good as your word.

Promise keepers may find it necessary to revisit agreements when conditions change. The key is how you change the agreement. If you cannot keep a promise, you should proactively go to the other party and attempt to negotiate a new agreement that is acceptable to both of you. Then, people can rest easy in your integrity. They know you will not forget your promises or unilaterally change your commitment.

Contrast a promise keeper with people who do not make strong promises:

They may avoid strong promises by saying “Sounds good.” or “I will try to . . . .” They may keep a private “out” that excuses them from keeping a promise. Or they may make a criminal promise with no intention of keeping it.

Shallow promises, private outs or criminal promises damage your reputation. Avoid them by keeping your promises.

Bottom line: Treat people with respect by telling the truth and keeping your promises. They will follow you confidently during today’s change and the changes to come.

If you do not have the reputation you want, start building credibility today. Tell the truth when a lie would be easier. Keep a promise that hurts. Proactively renegotiate a commitment that you have the power to ignore or unilaterally change. Building your reputation takes time and repeated testing under pressure. Be consistent and patient to grow your reputation.

If you are already known for your character, protect your good name by continuing to be a truth teller and a promise keeper. Then, your character will complement your commitment, competence and capacity to change.

At the Gaps, Go Slow to Go Fast

Allen Slade

In organizations, faster change is your only long term advantage. But sometimes, speed prevents people from making the change successfully. By going fast, you create errors and friction, causing the change to be less successful.

My sons are on a team in the FIRST Lego League robotics competition. They program a wheeled robot to hit levers, fling a ball and grab things. The final task is to drive up a ramp and park on a teetering platform.

The robot must be centered or the platform will tilt and the robot will fall off. The robot’s behavior is unpredictable, especially at gap between the ramp and the parking spot.

When you are leading change, do you go too fast? Do you “program” your team to slam through obstacles as quickly as possible? You can go fast to go slow. Don’t be surprised if your change goes off track.

When you are leading change, do you go too fast? Do you “program” your team to slam through obstacles as quickly as possible? You can go fast to go slow. Don’t be surprised if your change goes off track.

The solution? Slow down at the gaps.

The robotics team reprogrammed the robot to climb the ramp slower. To jump the gap, they slowed the robot down even more. Jumping the gap is less violent and the robot is less likely to be thrown off kilter.

Bottom line: Go as fast as you need for change. But if your change is going off track, go slow to go fast.

As a wise change leader, you need to know when to go slow and when to go fast. At the major transition points, allow people time to make sense of the change they face. By taking the time for dialogue and insight, you can create intelligent change. Go slow to go fast, and you can increase the odds of reaching your goal safely.

The Problem with Problem Solving

Allen Slade

“We have a problem.” If someone says that, do you get a sinking feeling? If you bring up problems with your team, do you feel the energy leave the room?

Let me be clear. Problem solving is good. As a leader, you must solve problems. Your ability to find and fix flaws is essential. Leaders need to find the error, reverse the decline, criticize the fault, hold others accountable and hold difficult conversations.

The problem with problem solving is that we use it too much. Relentless fault finding decreases energy for you and the people around you. If you see everything as a problem, you drain your own energy. If a person frequently finds fault with you, you lose energy for that relationship. If a given task or situation seems to be laden with problems, you lose energy for that task or situation. You may need to continue in that relationship, task or situation, but your heart won’t be in it. Excessive problem solving is a problem.

While problem solving drains energy, appreciation builds energy. As a leader, you must be able to appreciate people and opportunities. You must be able to recognize what is good, true, effective and beautiful. You must reward progress, not just punish shortfalls.

To manage the energy of the people you work with, be mindful of your appreciation ratio. The tipping point seems to be 1/3 problem solving to 2/3 appreciation. When problem solving exceeds 1/3 of interactions, we tend to lose energy for that person, task or situation. When appreciation is 2/3 or more, we tend to build energy. Aim for an appreciation ratio of at least 67%.

Managing my own appreciation ratio has fundamentally changed my outlook on life. I used to see consulting as problem solving. If my client hired me to solve problems, then I had to be scanning for problems, thinking about problems, talking about problems and solving problems. With my problem radar on full power, it is no surprise that I found lots of problems. I completed many consulting assignments thinking “With all these problems, I’m glad I don’t work here.”

Now, I look at my clients from the perspective of success. I look for my client’s strengths – what is good, true, effective and beautiful about what they do. With my appreciation radar on full power, I appreciate my clients more and I project a positive vibe. I still solve problems, but I solve them in an atmosphere of appreciation. Now, when I complete an assignment, I think “This is a great company!”

There is a strategic problem with a low appreciation ratio. Focusing on strategic weaknesses is more than depressing. It is bad strategy. Ford Motor Company got into retail banking in the late 1980s and 1990s. Ford was good at car loans and leasing, but it was not very good at retail banking. A problem solver would work on banking until it was fixed. Ford tried to turn the banks around for a few years , but the company wisely decided to cut its losses and sell the banks. Then, Ford was able to focus on its core competencies in auto financing and manufacturing.

Try a mini-experiment today: focus on what is good, true and effective. Look for strengths more than problems. When you interact with people, notice your appreciation ratio. When it drops below 67%, turn down your problem radar and turn your appreciation radar on full power. In the short term, you will perceive things more positively. In the long term, you will build stronger people, more effective systems and a healthier organization by leveraging competency rather than focusing on failure.

To solve the problem with problem solving, go positive. Problem solve less and there won’t be as many problems. Appreciate more, and you will build your success as a leader.

Smart Goals

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders set goals for themselves and others. The most powerful goals tend to be specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Here are my thoughts on how to set smart goals:

Specific – the goal states a specific outcome or action. If your goals are stated only as outcomes, there may be no obvious steps to take. You don’t want to be like the basketball coach who talks about winning but has no plan for today’s practice. If all of your goals are actions, you can get disconnected from your ultimate purpose, like the basketball coach who focuses only on holding a great practice. I encourage my clients to set a mix of outcome goals and action goals, covering both the end to be achieved and the means to that end.

Measurable – the goal can be assessed against an objective standard. We tend to value what we measure and measure what we value. Without measures, your goal is light-weight. The measures can be hard, in the form of objective numbers. Numeric metrics are straightforward, but easy to measure does not equal important. Your measures may need to be soft, in the form of assessments of key stakeholders. And some measures are binary: Did the desired activity or outcome happen (yes or no)? Different goals require different metrics, but all goals should be measurable.

Actionable – the goal can be acted on by the person who holds the goal. Your goals are powerful only if you can personally take steps to accomplish the goal. As a leader, set goals with your team that are in their realm of possiblity. Otherwise, you will undermine their motivation and your credibility.

Realistic – the goal is difficult but attainable. Harder goals increase performance. But goal difficulty has limits. When a goal becomes unrealistic, its power disappears. When setting goals for ourselves, you should think through your odds of success. When setting goals with others, have an open two-way discussion of the goal to get the level of difficulty right. Difficult goals are good, but they must be attainable.

Timebound – the goal has clear timing, either a date or a rate. For one-time goals, use a due date. “I will accomplish this action by April 1 of next year.” For ongoing goals, use a rate of action or outcome. “I will sell $100,000 of new consulting business per month.” Without a date or rate, a goal is not specific or difficult.

With all five smart features, your goals will have maximum impact. And, all five feature should reinforce each other. The specific actions should be realistic, the metrics should have a date or rate, etc.

It is possible to go overboard – to be too smart for your own good. With my leadership coaching clients, less is usually more. At first, I encourage them to focus on just one or two behaviors to change. Taking on too many changes creates frustration rather than change. We often start with goals that are general. For example, a client increasing visibility might start with “Notice how much airtime I take up in meetings.” This is not specific, but sometimes that is all that is needed to trigger change. If a stronger trigger is needed, we move to a more specific goal, such as “I will speak up twice in every meeting.” If that doesn’t works, we can move to an even smarter goal, such as “In Monday’s meeting, I will comment twice on product quality. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story.”

Almost every goal could benefit from being a bit smarter. Yet consider what works for you. Some people thrive on smart goals tightly linked to their life purpose and their daily schedule. Others need nothing more than a Post-it reminder. And, once your goal is in play, notice how it works for you. If you are making progress and accomplishing what you want, that goal is right for you. If your goal is not working, consider making your goal smarter.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

It is also important to agree on metrics and time for each goal at the beginning. Then, during the peformance review, you and your team member will be on the same page with feedback.

Bottom line: You should set specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound goals, for yourself and for others. When setting goals with others, have lots of dialogue. Be smart – create dialogue, insight and powerful goals to drive performance.

Steps for Planned Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

A model for planned change can help you navigate your way through uncharted territory. There are a lot of different change models out there, and many of them are numbered. Here is a partial list:

As a change leader, should you use a change model? If so, which one?

The bottom line: Use a planned change model. As for which model, go with what works for you and know when to yield.

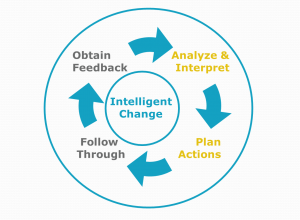

I generally recommend a planned change model for my clients. A model can help simplify a complex situation, provide a common language for discussing change in your organization and can focus attention to guide action. In other words, a planned change model gives insight for intelligent change.

There are differences in the number, sequence and timing of the steps, but these differences are not very important. Which planned change model you use is a matter of preference and politics. If your preference holds sway, use what works for you. If the powers that be insist on a different model, you can yield with a clear conscience. I have scars from arguing too hard for change models that were not in vogue. Almost any planned change model will help chart your course through the change.

John Kotter’s 8-step model for leading change works as well as any, so I use it often. Here are his eight steps:

1. Establish a sense of urgency. I recommend an analysis of the forces for change and the forces for stability. If the forces for change are not great enough, regroup and restart.

2. Form a powerful guiding coalition. Get the right people with sufficient knowledge, influence and commitment to guide the change. If you initiated change without the juice to make it happen, get the power brokers on board.

3. Create a vision. This should be a powerful, brief and memorable summary of the change – what is changing, why and how it affects us. A fuzzy vision will make the rest of the process harder.

4. Communicate the vision. Get the vision out there and get all parties to join the process. But don’t see communication as a “tell and sell” campaign. Engage in dialogue. Underscore the key points and get your employees’ feedback, insights and creativity. Change your plan early and often based on this dialogue.

5. Empower others to act on the vision. You can’t do it all. Bet on your people. Encourage them to act without your tight control. The vision for change sets the boundaries and general direction. Let others sweat the details.

6. Plan for and create short-term wins. Change is hard work. Change is especially hard in the middle, after the initial excitement has died down and before the final success is clear. Discouragement must be managed. Celebrate your team’s success early and often.

7. Consolidate improvements and produce still more change. Build on your success. Leverage your successes and learn from your failed experiments.

8. Institutionalize new approaches. Lock in the new way of doing things with congruent changes to your strategy, structure, systems and culture.

If this 8-step model resonates with you, use it. If not, look for another planned change model. A good road map provides insight for intelligent change.

Faster Change is Your Only Advantage

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

In my post on Making Sense of Change, I highlighted the need to devote energy to sense-making during seasons of change. As a leader, how long are your seasons of change? When will things get back to normal?

The rate of change is accelerating. Moore’s Law originally applied to transistors, but the pattern of exponential change affects every process and every corner of your organization. Everything is accelerating – bigger changes, more changes, at a faster pace. Even the pauses are disappearing. When you complete a major change, you are likely to move on to the next change.

Bottom line: Change is the new normal. And your only sustainable competitive advantage is your ability to change faster than the competition.

Your organization’s ability to survive depends on its reflex time. You will prosper as a leader if you are on the front edge of change. And your team needs to get on board with the new normal.

Let’s think through the commitments, competencies and capacities needed for faster change.

Commitment to change. Change is here to stay. Don’t waste energy complaining about the latest change or wishing for past stability. Embrace the change. Look forward to change. Jump into the next challenge.

As a leader in the midst of change, you help set the tone for your team. Be a cheerleader for change. Get others excited about the bright future.

Growing change competence. As change accelerates, you need to be better at change. Treat every change as an opportunity to master new skills. Look for new ways of doing things. Be the first to tackle the new challenge, play with the new system, apply the new concept or talk to the new person. Today’s change is practice for tomorrow.

As a leader, you need to develop your team’s change competence also. Coach them in change competence. Take risks with your team’s decision making – empower them to act without your tight control. Their growth today will make tomorrow’s change easier for both of you.

Capacity to change. It is not enough to be able to change. You need the capacity to change quickly and often. You have to multi-task competing changes. You must accelerate your sense-making so you can quickly climb out of the performance valley of change. And, you cannot rely exclusively on carefully planned change. You need to able to “ready, fire, aim” and just do something.

As a leader, you need to encourage your team’s capacity to change. Push your team to the point of change fatigue. Help them be quicker at sense-making. Get them to move beyond planned change so they can just do something. Then, their change muscles will have more capacity the next time.

You increase competence by mastering new skills. You increase capacity by using those new skills over and over again. I mastered the basic competence of riding a bike many years ago. I recently rode my first century. It was a major challenge to bike a hundred miles in one day. I needed commitment, competence and capacity. I had to commit to finishing the ride. I had to master newer cycling technology – a new road bike instead of my trusty old hybrid, shoes that lock into the pedals and sports drinks that taste like cold sweat. And, most importantly, I had to increase my capacity to go longer and faster by riding hundreds of miles before the actual century.

The demands of change are massive. Dialogue and rest can help you avoid be overwhelmed.

Dialogue. Surround yourself with people who support and encourage you in times of stress.

- Rely on your family members and close friends for encouragement. Talk about your changes. Talk about the impact on you physically, mentally and emotionally.

- Form a circle of trusted advisors with whom you can talk through the challenges and your change approach.

- Consider getting yourself a leadership coach.

Rest. Take a break from the relentless pace of change.

- As needed, stop and catch your breath. Consider using centering or some other activity to still your hands, quiet your mind and calm your heart.

- Schedule times of rest. Every Sunday, I take a sabbatical from work – largely avoiding email, Twitter and this website. I catch up on sleep that day and I think about the big picture. On Monday morning, I am ready to accelerate back onto the change expressway.

As a leader, you must also provide dialogue and rest for your team. If you are pushing them to the point of change fatigue, make sure they recover well. Support them in the midst of change. Talk about the change. Support them with advice. Thank them for their efforts. And, give some breathing room for them to recuperate.

Change is the new normal. The rate of change is accelerating. Your ability to change faster than the competition is your only sustainable competitive advantage. If you are overwhelmed by change, take a quick break right now. Then get a little help from your friends.

Making Sense of Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Can you perform at your maximum – can you give 100% – in the midst of change? Should you demand 100% from your team when they are facing change? Pushing hard for short term performance can undermine long term success and maximum growth. We need to leave breathing room for change to work its way out. We need to plan for a season of sense-making.

Meryl Louis defines sense-making as the psychological process of revising our cognitive map to figure out “what is new, different and – particularly – what was unanticipated.” Sense-making rewrites a large cognitive map:

- Understanding new duties, responsibilities, power structures, and peer relationships.

- Clarifying the new path to success, including new performance criteria and new goals.

- Developing new skills and behaviors to master the new role.

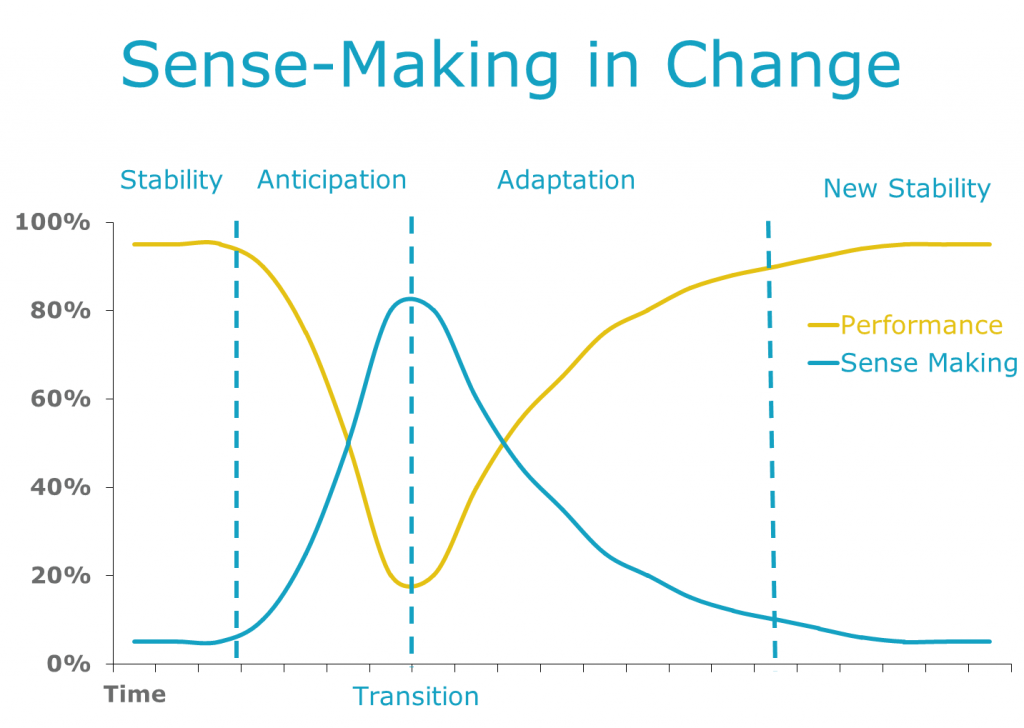

Here is a picture of sense-making in action:

When you go through a transition, you should expect a decline in performance. You will need to spend energy and time making sense of the new situation. In the midst of change, I ask my clients two questions:

How deep is your valley? The larger the transition, the deeper the expected decline in performance. A reorganization which just moves some boxes on the org chart will have little impact on your performance. A major change of systems, strategy, structure and culture will require more sense-making.

Where are you on the sense-making curve? The highest level of sense-making tends to occur at the point of transition. The hallway conversations linger longest the day the new strategy is announced. The job change is nested in farewell lunches and new employee orientation programs to give breathing space for sense-making.

When you lead others through change, you should plan for your team’s sense-making. This is tough when the change is triggered by competitive pressure. No matter what the performance demands, you can’t just wish away the need for sense-making. During the change, help your team through the valley. Give them perspective, just-in-time information and support to help move them to the other side.

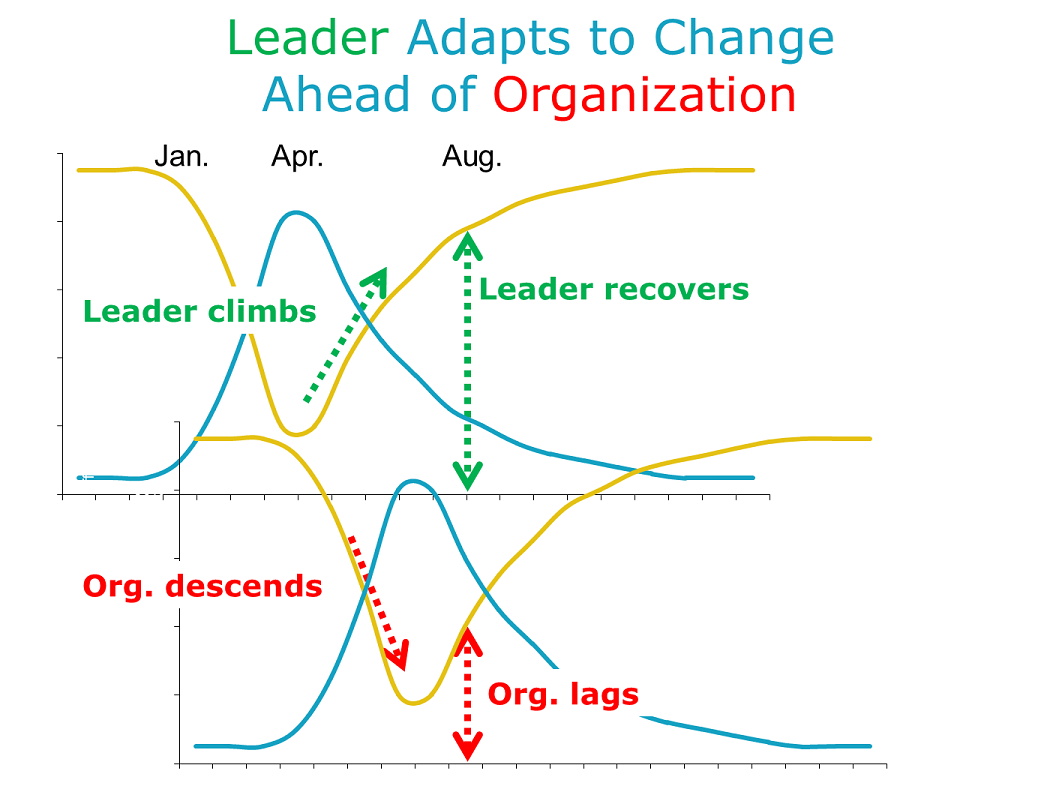

If change is rolled out top-down, the change leader will be further along the curve. You start planning a change in January and announce the change in April. You will be at the peak of sense-making and stress at the April announcement, but your organization is just starting the process. By August, your performance is almost back to pre-change levels, but your organization is just bottoming out.

This lag in sense-making can cause frustration and impatience. As a leader, you can falsely blame your team for not getting with the program. The reality is they need more time because they started the transition after you.

As a leader, plan for the season of change. Know where your people are. “How deep is their valley?” “Where are they on the sense-making curve?” Truly lead, not just in planning the tasks of change but also in making sense of the new future. Provide perspective, just-in-time information and breathing space to help them climb the far side of the sense-making valley.