When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

The Leader’s Tipping Point

By Allen Slade

Leadership is about creating sustainable performance in your team. Jim Clawson points out that effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a post on The Tipping Point of Performance, I talked about managing energy in others to create sustainable performance. As a leader, you have a proven track record of results. You combine competence, capacity and committent to success, so people are willing to follow you. But is your performance sustainable?

Bottom line: As a leader, you have to manage your own energy. Know your performance curve, watch for signs of an impending performance crisis and take dramatic action as needed.

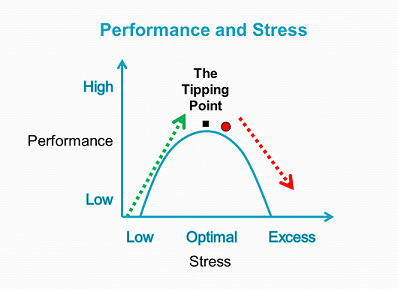

The performance curve is just as true for you as it is for the people you lead. We all experience this inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between your level of stress and your performance holds, but only in the green zone.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

Bottom line: Push youself, but know your own tipping point. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Manage your own stress wisely, especially on the dangerous part of the performance curve.

Stress reduction strategies. Whether you are at the top of the green zone or at the tipping point, try stress management strategies. Simplify your life. Practice centering. Off load non-essential work. Get help from your boss, in terms of more people, more resources or more time. Ask your colleagues for support. Delegate to your team.

Develop yourself. Long-term, grow your capacity for performance to avoid a stress-induced performance crisis. Develop new skills. Practice skills to the point of mastery. Practice for speed, not just completion. If you can write methodically, practice writing under a deadline. (Blogging three times a week is speeding up my writing!) Coaching can help, whether you are an executive, leader or golfer. At Slade & Associates, we coach executives and leaders to maximize their performance. There are certain things we don’t do, so you would do well to find your own golf coach.

Your urgency in reducing your stress depends on your position on the performance curve:

Top of the green zone. If you push harder but don’t see much improvement, you may be approaching the top of your green zone. Be careful, because you could hit your tipping point. Be alert for further stress, and consider strategies to reduce stressors or increase your performance capacity.

The tipping point. Approaching your tipping zone is dangerous. If familiar tasks become harder, if your inbox is overwhelming, if you snap at reasonable requests or if you work longer with fewer results, you may be at your tipping point. At the tipping point, you still have time. You can think. You can experiment with one stress reducer at a time. Take action now to reduce your stress. Climb back down into the green zone while you can still think clearly.

The red zone. Passing your tipping point is catastrophic because of the accelerating downward spiral of performance. To get out of the red zone, aggressively implement stress management strategies. Make a plan that combines at least two or three big stress reducers – simplify, center, get support from your boss, delegate, etc. Make smart requests ask your boss for support or delegate. Whatever the details, take dramatic action. In the red zone, you must act now.

A lifeguard. I must confess: This red zone advice may not work. The downward spiral of performance undermines your decision making and behavioral flexibility. If you are drowning, sometimes you can’t save yourself. You need a lifeguard who will know you need help and step in during a crisis. Your lifeguard could be a friend, a mentor, a coach or your family. Before a red zone crisis, build strong relationships. Be transparent, accountable and open to constructive feedback. Then, if you are drowning in stress, you will have someone willing to dive in to save you.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for yourself and for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

The Tipping Point of Performance

Allen Slade

I love sports movies, especially about underdogs. The critical moment is when the coach or loved one gets the underdog fired up. I love Rocky II, when Talia Shire lights Rocky’s fuse from her hospital bed and Remember the Titans, when Denzel Washington gives a moving call for unity in the Gettysburg cemetery.

As a leader, do you try to fire up your team? Be careful. If you play with fire, you can get burned.

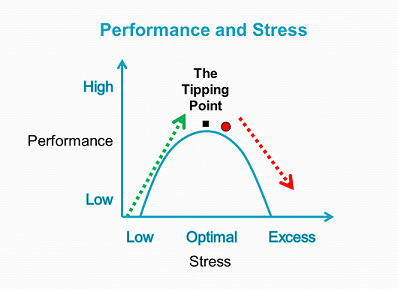

Clearly, there are times when you need to establish a sense of urgency. But asking for extraordinary effort can backfire. As the performance curve below shows, there is an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between stress and performance does hold, but only in the green zone.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

The problem hits at the top of the curve. When a person reaches the tipping point, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance leads to a downward spiral in the red zone. People become anxious. They act indecisively, work slower or make more mistakes. As their performance decreases, their anxiety increases, further decreasing their performance. Notice the red marble at the top of the performance curve. In the red zone, the marble accelerates down the curve of poor performance. As a leader, if you push a person too far, their performance drops. And, their performance will continue to get worse because of the downward spiral.

Bottom line: Push for performance, but avoid the tipping point for stress. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Aim for high performance, not peak performance. I coach leaders to avoid pushing people to their tipping point. If the tipping point is at 100% performance, aim for 90 or 95%. Then, your team member has a stress buffer. If there is a coffee spill that wipes critical data or a car wreck going to the big meeting, they will have the psychological reserves to get through it. If you push to get the full 100%, your people may tip into the red zone.

Develop your people. If you wish to increase performance, but a person is near the tipping point, think development first, motivation later. Increase their competence and capacity, so they can perform better while maintaining an essential stress buffer.

Be a lifeguard. Your people can drown in stress. The downward spiral of performance undermines decision making and behavioral flexibility. If someone is in the red zone, you may need be their lifeguard. Watch for signs of stress in your team members, watching for people at the tipping point or in the red zone. Then, throw them a life line. Offer more resources, renegotiate deadlines, offer them time off to refresh and rest. Be creative – think of the rousing speech that fires up the underdog, then do the opposite.

Know your team. Everyone is different. The people you lead have different capabilities and stress tolerances. They will show different warning signs of a stress-induced performance crisis. Get to know your people before a crisis. Have regular dialogue with every team member. Seek insight about their performance patterns, personal stressors and individual signs of overload. This will equip you to be a stress lifeguard.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

Steps for Planned Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

A model for planned change can help you navigate your way through uncharted territory. There are a lot of different change models out there, and many of them are numbered. Here is a partial list:

As a change leader, should you use a change model? If so, which one?

The bottom line: Use a planned change model. As for which model, go with what works for you and know when to yield.

I generally recommend a planned change model for my clients. A model can help simplify a complex situation, provide a common language for discussing change in your organization and can focus attention to guide action. In other words, a planned change model gives insight for intelligent change.

There are differences in the number, sequence and timing of the steps, but these differences are not very important. Which planned change model you use is a matter of preference and politics. If your preference holds sway, use what works for you. If the powers that be insist on a different model, you can yield with a clear conscience. I have scars from arguing too hard for change models that were not in vogue. Almost any planned change model will help chart your course through the change.

John Kotter’s 8-step model for leading change works as well as any, so I use it often. Here are his eight steps:

1. Establish a sense of urgency. I recommend an analysis of the forces for change and the forces for stability. If the forces for change are not great enough, regroup and restart.

2. Form a powerful guiding coalition. Get the right people with sufficient knowledge, influence and commitment to guide the change. If you initiated change without the juice to make it happen, get the power brokers on board.

3. Create a vision. This should be a powerful, brief and memorable summary of the change – what is changing, why and how it affects us. A fuzzy vision will make the rest of the process harder.

4. Communicate the vision. Get the vision out there and get all parties to join the process. But don’t see communication as a “tell and sell” campaign. Engage in dialogue. Underscore the key points and get your employees’ feedback, insights and creativity. Change your plan early and often based on this dialogue.

5. Empower others to act on the vision. You can’t do it all. Bet on your people. Encourage them to act without your tight control. The vision for change sets the boundaries and general direction. Let others sweat the details.

6. Plan for and create short-term wins. Change is hard work. Change is especially hard in the middle, after the initial excitement has died down and before the final success is clear. Discouragement must be managed. Celebrate your team’s success early and often.

7. Consolidate improvements and produce still more change. Build on your success. Leverage your successes and learn from your failed experiments.

8. Institutionalize new approaches. Lock in the new way of doing things with congruent changes to your strategy, structure, systems and culture.

If this 8-step model resonates with you, use it. If not, look for another planned change model. A good road map provides insight for intelligent change.

Making Sense of Change

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Can you perform at your maximum – can you give 100% – in the midst of change? Should you demand 100% from your team when they are facing change? Pushing hard for short term performance can undermine long term success and maximum growth. We need to leave breathing room for change to work its way out. We need to plan for a season of sense-making.

Meryl Louis defines sense-making as the psychological process of revising our cognitive map to figure out “what is new, different and – particularly – what was unanticipated.” Sense-making rewrites a large cognitive map:

- Understanding new duties, responsibilities, power structures, and peer relationships.

- Clarifying the new path to success, including new performance criteria and new goals.

- Developing new skills and behaviors to master the new role.

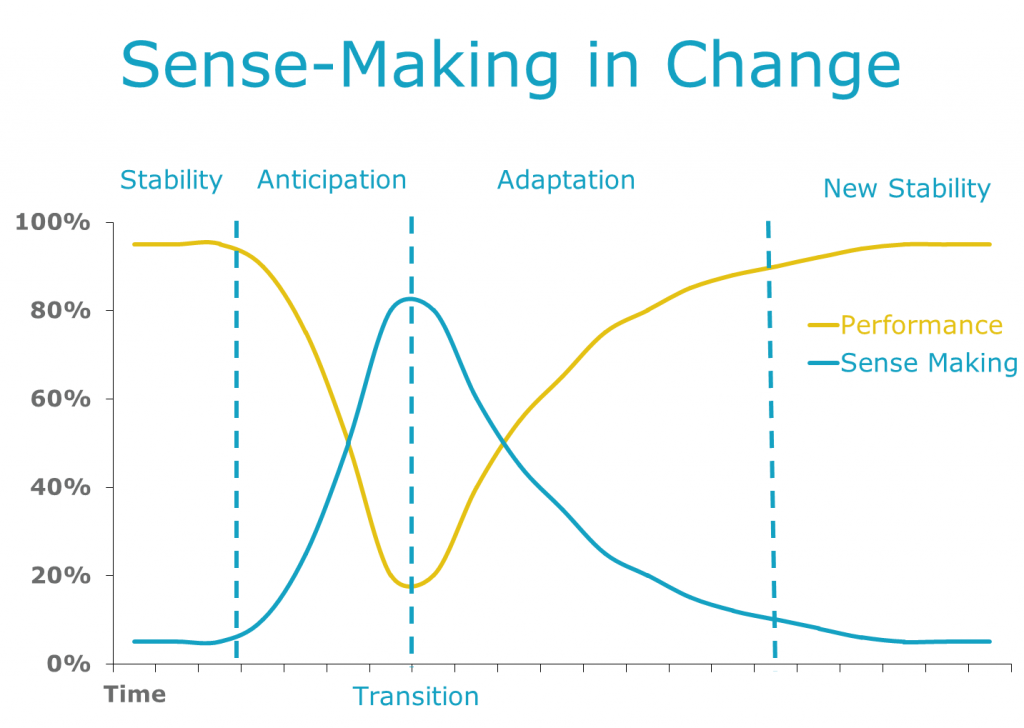

Here is a picture of sense-making in action:

When you go through a transition, you should expect a decline in performance. You will need to spend energy and time making sense of the new situation. In the midst of change, I ask my clients two questions:

How deep is your valley? The larger the transition, the deeper the expected decline in performance. A reorganization which just moves some boxes on the org chart will have little impact on your performance. A major change of systems, strategy, structure and culture will require more sense-making.

Where are you on the sense-making curve? The highest level of sense-making tends to occur at the point of transition. The hallway conversations linger longest the day the new strategy is announced. The job change is nested in farewell lunches and new employee orientation programs to give breathing space for sense-making.

When you lead others through change, you should plan for your team’s sense-making. This is tough when the change is triggered by competitive pressure. No matter what the performance demands, you can’t just wish away the need for sense-making. During the change, help your team through the valley. Give them perspective, just-in-time information and support to help move them to the other side.

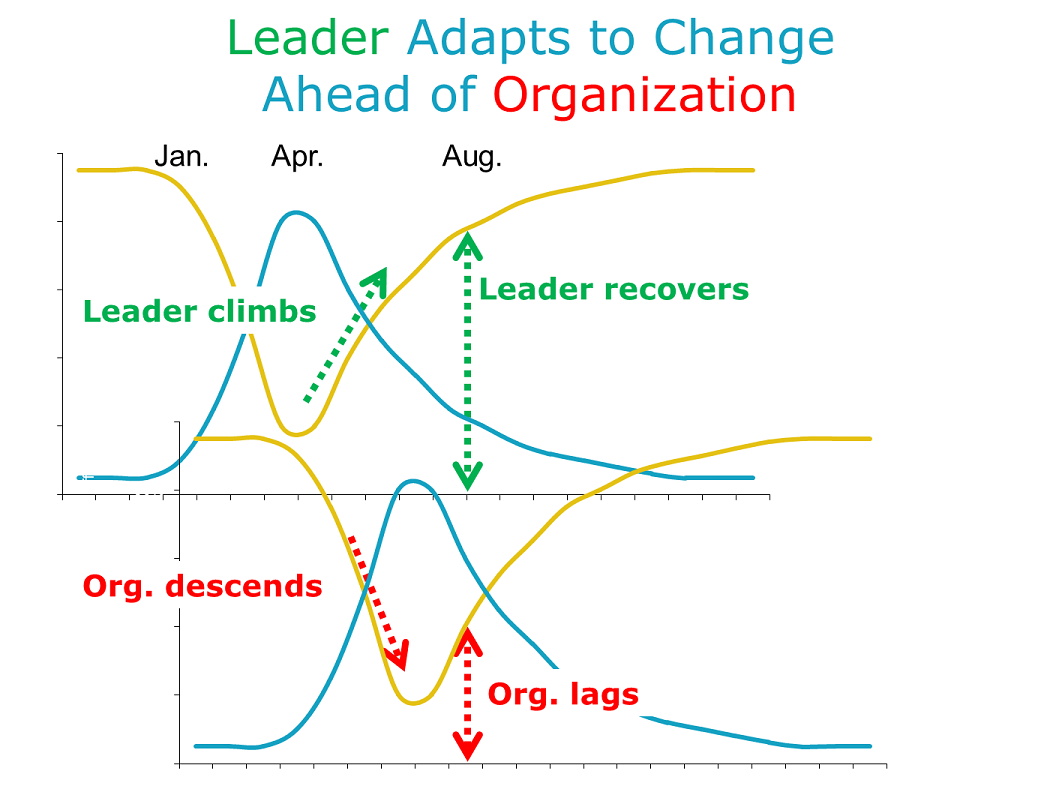

If change is rolled out top-down, the change leader will be further along the curve. You start planning a change in January and announce the change in April. You will be at the peak of sense-making and stress at the April announcement, but your organization is just starting the process. By August, your performance is almost back to pre-change levels, but your organization is just bottoming out.

This lag in sense-making can cause frustration and impatience. As a leader, you can falsely blame your team for not getting with the program. The reality is they need more time because they started the transition after you.

As a leader, plan for the season of change. Know where your people are. “How deep is their valley?” “Where are they on the sense-making curve?” Truly lead, not just in planning the tasks of change but also in making sense of the new future. Provide perspective, just-in-time information and breathing space to help them climb the far side of the sense-making valley.