When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Principles of Leadership Are Outdated

Allen Slade

When I teach leadership to business students, I often open the first class by asking students about leaders they respect. Mahatma Gandhi, George Patton, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Steve Jobs are often mentioned. Some students talk about their athletic coach or a former boss.

Then, we get to the heart of leadership. To save you the cost of tuition, here are the highpoints:

The “Great Man” theories of leadership don’t work.

There is no one best way to lead. The best way to lead depends on the situation.

The best leaders are not students of leadership.

There are no simple rules. I discourage imitating role models. I attack leadership trait theories. I undermine leadership style theories. Being the best leader you can be is difficult and complicated.

Those who look for simple answers are understandably disappointed.

Yet, there is a straightforward approach to leadership in my class. Be a student of followership and collect lots of data.

Be a student of followership. Don’t waste time studying leaders or leadership. Study the people you lead. The best leaders have incredible curiosity about the people around them. They ask people what’s important to them, then they think hard about the implications. They check for understanding by asking more questions. The best leaders shape their leadership behavior for their followers.

Collect lots of data. To understand people, the best leaders are hungry for information. They collect data with direct observation of the words, tone and emotions of others. They ask lots of questions. And they suck every bit of value out of any quantitative data they can get, through surveys, 360 reports, attrition data, customer data, etc.

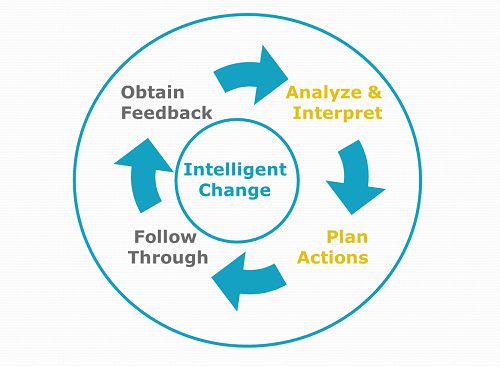

For the visually oriented like me, here is how I capture this vision of leadership:

With a commitment to know the people you lead and a hunger for more data, you can bootstrap your leadership. You can create mini-experiments based on your tentative knowledge of people, and then correct your actions based on their feedback. You will develop a personal, flexible leadership style. And, I suspect, your impact as a leader will expand well beyond what you would achieve if you had simply tried to imitate the great leaders of the past.

The Problem with Problem Solving

Allen Slade

“We have a problem.” If someone says that, do you get a sinking feeling? If you bring up problems with your team, do you feel the energy leave the room?

Let me be clear. Problem solving is good. As a leader, you must solve problems. Your ability to find and fix flaws is essential. Leaders need to find the error, reverse the decline, criticize the fault, hold others accountable and hold difficult conversations.

The problem with problem solving is that we use it too much. Relentless fault finding decreases energy for you and the people around you. If you see everything as a problem, you drain your own energy. If a person frequently finds fault with you, you lose energy for that relationship. If a given task or situation seems to be laden with problems, you lose energy for that task or situation. You may need to continue in that relationship, task or situation, but your heart won’t be in it. Excessive problem solving is a problem.

While problem solving drains energy, appreciation builds energy. As a leader, you must be able to appreciate people and opportunities. You must be able to recognize what is good, true, effective and beautiful. You must reward progress, not just punish shortfalls.

To manage the energy of the people you work with, be mindful of your appreciation ratio. The tipping point seems to be 1/3 problem solving to 2/3 appreciation. When problem solving exceeds 1/3 of interactions, we tend to lose energy for that person, task or situation. When appreciation is 2/3 or more, we tend to build energy. Aim for an appreciation ratio of at least 67%.

Managing my own appreciation ratio has fundamentally changed my outlook on life. I used to see consulting as problem solving. If my client hired me to solve problems, then I had to be scanning for problems, thinking about problems, talking about problems and solving problems. With my problem radar on full power, it is no surprise that I found lots of problems. I completed many consulting assignments thinking “With all these problems, I’m glad I don’t work here.”

Now, I look at my clients from the perspective of success. I look for my client’s strengths – what is good, true, effective and beautiful about what they do. With my appreciation radar on full power, I appreciate my clients more and I project a positive vibe. I still solve problems, but I solve them in an atmosphere of appreciation. Now, when I complete an assignment, I think “This is a great company!”

There is a strategic problem with a low appreciation ratio. Focusing on strategic weaknesses is more than depressing. It is bad strategy. Ford Motor Company got into retail banking in the late 1980s and 1990s. Ford was good at car loans and leasing, but it was not very good at retail banking. A problem solver would work on banking until it was fixed. Ford tried to turn the banks around for a few years , but the company wisely decided to cut its losses and sell the banks. Then, Ford was able to focus on its core competencies in auto financing and manufacturing.

Try a mini-experiment today: focus on what is good, true and effective. Look for strengths more than problems. When you interact with people, notice your appreciation ratio. When it drops below 67%, turn down your problem radar and turn your appreciation radar on full power. In the short term, you will perceive things more positively. In the long term, you will build stronger people, more effective systems and a healthier organization by leveraging competency rather than focusing on failure.

To solve the problem with problem solving, go positive. Problem solve less and there won’t be as many problems. Appreciate more, and you will build your success as a leader.

Balancing Airtime in Your Meetings

Allen Slade

Some people think meetings are just a waste of time. At one level, meetings exist to share information and to make decisions. (It doesn’t always work, but that’s the plan.) At another level, leaders should see meetings as leadership development opportunities. Jim Clawson says effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a meeting, energy shows up most clearly as spoken comments. One way to think about managing the energy in meetings is airtime.

Airtime is the percent of time you are the focus of the team’s attention (talking, writing on the board, etc.). For a five person team with equal attention, each person should be the focus of attention about a fifth of the time – 20% airtime. A person dominating the conversation has 50% or more airtime.

It is rare that each person gets exactly the same airtime in a meeting. You may have more airtime because your expertise or passion fits the topic.

Once you get a handle on your own airtime in meetings, notice the airtime of the people around you. Some people may dominate the meeting (take up most of the airtime) while other people almost never speak. In some meetings, unbalanced airtime makes sense. The high airtime person may have unique information or expertise that will help move the meeting ahead.

All too often, though, unbalanced airtime comes from ineffective meeting dynamics. There may be personality differences that drive airtime, such as extroverts speaking endlessly and introverts staying quiet. There may be cultural norms that prevent some from speaking up, such as power distance or gender roles. There may be managers who love to hear their own voice. There may be politics at work, with the deliberate attempt to keep certain ideas or people out of the discussion.

If you want to balance out airtime, here are some tactics:

Draw in the silent majority. Ask a quiet person a direct question. Often, when you break the ice, they will find it easier to participate in the future.

Gently redirect dominators. If someone takes up too much aritime, use an appropriately assertive statement such as “Let’s hear from some other people now.”

Restructure the conversation. Try beginning the meeting with an icebreaker exercise or by asking everyone to briefly report on activities or results. During the meeting, ask everyone to comment on the issue or decision.

Get a facilitator. If the meeting continues to be ineffective, look to bring in a facilitator. The facilitator can help you redesign the meeting beforehand. He or she can also help with in-the-moment interventions to get the meeting rebalanced.

When managing airtime in your meetings, you are not striving for perfect balance. Instead, you are looking to get everyone engaged in the meeting. Balanced airtime will make meetings more interesting. It will help your information sharing and decision making more effective. Balanced airtime will maximize leadership development of others. And, actively managing airtime for yourself and others will become another tool in your leadership toolbox.

Are You Just Showing Up?

Allen Slade

You probably had at least one meeting today. Why were you in that meeting? Woody Allen said “90% of life is just showing up.” He’s wrong. Leaders go to meetings to make a difference.

A meeting is like a journey:

You can focus on your next step, looking to avoid a misstep. This short range focus may help you avoid gaffes, but you won’t make much of a difference.

You can think about the next mile – how will we reach our goal for today? With a medium range focus, you can help make today’s meeting a success.

Or you can look to the horizon, and think about where you want to be in the future. With a long range focus, you are looking ahead to future meetings, future decisions and future leadership opportunities. You treat each meeting as an opportunity to grow your influence.

The best leaders do not choose between short, medium and long range focus in a meeting – they do all three at once. They craft a great comment while avoiding gaffes, they make today’s meeting a success and they develop their leadership, all at the same time.

Let’s focus on the long range impact of your meeting participation. As a leader, you should be mindful of your leadership presence in meetings. Do you appear timid? If so, you may not be seen as a leader. Do you talk too much? You may undermine your standing as an empowering leader or an effective team player. Let me suggest three ways you can be mindful of your meeting behavior.

1. If you want to manage your leadership presence in meetings, try noticing how much airtime you take up in meetings.

Airtime is the percent of time you are the focus of the team’s attention (talking, writing on the board, etc.). For a five person team with equal attention, each person should be the focus of attention about a fifth of the time – 20% airtime. A person dominating the conversation has 50% or more airtime.

It is rare that each person gets exactly the same airtime in a meeting. You may have more airtime because your expertise or passion fits the topic.

The point is not to set a specific percentage target. Just notice your airtime.

“Noticing airtime” is not a smart goal. It is not specific, measurable, actionable or time-bound. I am a big fan of smart goals as a powerful source of change, but they are not the only way to develop your leadership. Sometimes just noticing something – being mindful – is all that is needed to trigger a major behavioral change.

2. If the airtime goal doesn’t lead to the change you want, try the rule of three: “I will make 3 valuable contributions in every meeting.” For this to work, you need to do your homework. Study the agenda, do some research, collect some reports and prepare to make a difference.

3. For maximum impact, create a SMART goal. Decide on a plan for your participation in each meeting that is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. For example, “In next Monday’s meeting, I will comment on the product quality topic on the agenda. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story. I will practice using both the data and the story with my coach before the meeting. I will use the data, the story or both in the meeting.”

See each meeting as a leadership development opportunity. Stay focused to make a difference. Avoid missteps, push the decision ahead and grow your leadership all at the same time.

Holding a Difficult Conversation

Allen Slade

You are gearing up for that difficult conversation. It may be about a broken commitment, setting a boundary to halt abusive behavior or feedback that is unexpected and unwanted. You want to navigate the emotional minefield to minimize the chance of a catastrophic explosion.

Now what? How do you plan the difficult conversation for maximum gain and minimum risk?

Start with the end. In a previous post, I recommended planning your difficult conversation by starting with the end. Have a clear definition of success. Be sure the potential reward of the difficult conversation is worth the cost.

Don’t procrastinate. Bad news is like bread. It is best fresh. After a few weeks you don’t want it in the house. If you need to have a difficult conversation, do it sooner rather than later. If you need time to think and plan or if you want to check your plan with a coach or mentor, fine. But think of waiting hours or days, not weeks or months.

Begin well. Plan your opening statement. Make it appropriately assertive, following this pattern: When you [specific behavior, attitude or thinking pattern], it makes me [specific negative outcome.] Here are some examples:

“When you roll your eyes while we talk, I feel disrespected.”

“When we discuss customer complaints, you tend to blame other employees. This makes me think you don’t see a need for change.”

Listen more and talk less. Be curious about the other person’s reaction. Look to discover why they act/feel/think like they do. Don’t argue. Don’t project an attitude of certainty. Practice active listening by reflecting back what they say and asking lots of clarifying questions.

Anticipate their reaction. At a basic level, put yourself in their shoes. If you were on the receiving end of this difficult conversation how would you react? Even better, figure out the other person’s general pattern of responding to feedback. Do they have a problem with feedback or are they generally open to feedback? Then, prepare for their reaction. Control your emotions, listen without agreeing and keep the conversation moving ahead to address the issues.

Seek mutual problem solving and commitment. The goal of a difficult conversation should be intelligent change. To change, you need to work with the other person, first to figure out how to change and then to get a commitment to change. You should aim for a smart request, a specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound proposal that the other person accepts.

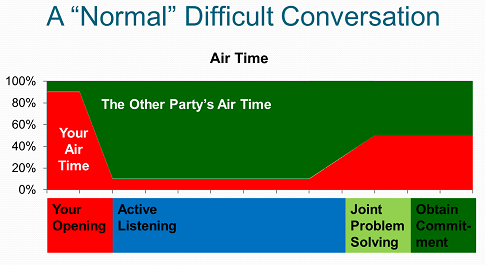

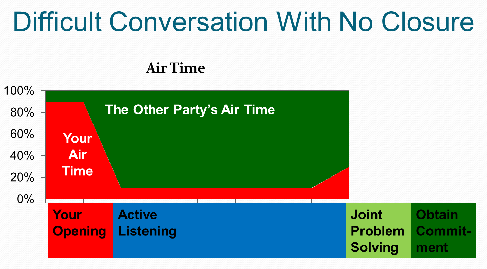

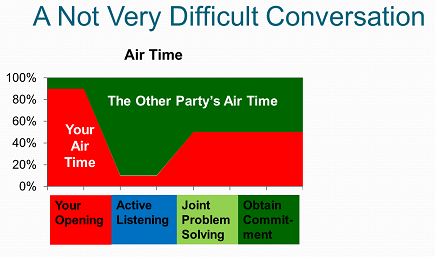

When you are at your best as a leader, your difficult conversation should follow this pattern.

You will give most of the airtime to the other person. Only during your brief opening will you do most of the talking. The longest part of the conversation is your active listening, where you may do 10% of the talking or less. When you get to joint problem solving and mutual commitment, you should look to do 50% or less of the talking.

Let’s be realistic. Some difficult conversations do not end with a solution. The other person may be too stubborn. If you do your part well, but the other person resists your efforts, your difficult conversation may turn out like this.  This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

I had a difficult conversation with an intern that started: “Dolly, your work has been slipping recently. Several people have reported smelling alcohol on your breath. I am concerned about your reputation. I am reluctant to assign you to important projects or have you go to meetings without me.” Dolly never admitted to a drinking problem. She did not agree to seek help. Yet, the issue disappeared overnight. When her internship ended months later, I gave her high performance ratings and a stellar recommendation.

If the other person has difficulty admitting a personal failing, there can still be change, but it will follow a different pattern. The individual you confront may go back to their office and think about what you said. Sometimes, that triggers the change you seek. They may never admit you were right or confess their shortcoming. That’s OK. You can live with the change even if you don’t get the apology.

The worst case is that change does not happen. Let’s acknowledge that we are dealing with adults. You can’t make the other person bend to your will. Give it your best shot – hold the most effective difficult conversation you can – but accept that they must decide whether to address your concerns. If they do not change, you can make other moves. You can set boundaries, end the relationship or get others involved in resolving the situation. Your key responsibility is to have the best difficult conversation you can without pretending you can control the other person’s reaction.

I have coached many clients on how to hold a difficult conversation. We work together to craft a powerful opening. We practice listening. We practice managing emotions. We even role play the difficult conversation. And then, my client goes off to hold the conversation. Surprisingly often, my client is surprised because the conversation turns out to be not very difficult at all.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

My thanks to executive coach Art Gingold for refining my thinking on difficult conversations.

Planning a Difficult Conversation? Start with the End

Allen Slade

You need to have a difficult conversation.

You know the conversation I mean. The conversation you keep putting off. You get butterflies just thinking about it. You know it will not be pleasant.

Your difficult conversation may be confronting someone about broken promises. It may be setting a boundary with someone who tramples over you or other people. You may be planning to share feedback that is unexpected and unwanted. Whatever the topic and whoever the other party, your difficult conversation feels like stepping into an emotional minefield.

As a leadership coach, I help clients hold the difficult conversation they have been putting off. To increase the odds of success, we work on two things: planning the conversation backwards and designing the conversation for maximum impact. Today, let’s think about how to plan your difficult conversation backwards. In other words, the best difficult conversations start with the end.

In planning a difficult conversation, always plan backward. Define a successful outcome for the difficult conversation before you hold it.

In planning a difficult conversation, always plan backward. Define a successful outcome for the difficult conversation before you hold it.

What does success look like? What change would you like to see in the other person? It might be a change in behavior, such as an employee returning phone calls promptly. It might be a more subtle change in thinking, values, attitudes, beliefs or expectations. Sometimes your desired change is not in the cards – the other person does not share your motivation, your definition of success or your norms. Sometimes, the endgame is just not feasible.

Is it worth it? How much risk will you take? Some difficult conversations put your relationship at risk. While things may improve, you can also harm the relationship by opening emotional wounds. A difficult conversation can also harm your credibility with your wider circle of influence. You must decide if the probable pain is worth the potential gain.

Starting with the end will show you a lot of difficult conversations should not happen:

Don’t tilt at wind mills. Risking much with little odds of success is not a good bet. Don’t confront your boss during your performance review meeting, especially if you expect poor ratings. Don’t ask the CEO snide questions during the strategy rollout. Don’t voice complaints about the company on your last day of work. If you don’t have the standing to make a positive change, save your energy and your reputation.

Don’t do it to let off steam. Don’t hold a difficult conversation because you “have” to tell them something. If you are holding a difficult conversation to vent your frustration, punish the other person or get something off your chest, just don’t. Unless you can visualize a successful change in the other person, don’t start a difficult conversation. Talk to your therapist, write in your journal or yell in your private closet instead.

Don’t call out strangers. Grocery store parenting advice, barroom etiquette instruction and roadway driver’s ed rarely stick. Worse, strangers can react strangely with nasty expressions, verbal abuse or violence. Little upside and potentially grave downside make difficult conversations with strangers a bad bet.

By avoiding fruitless difficult conversations, you will be happier and healthier. You will also have more energy for the conversations that have the right end game. Then, with the proper planning, you can improve a relationship, change someone’s ineffective behavior or chart a new direction. You can have difficult conversations with the outcomes you seek, if you start with the end.

Leading in Stormy Weather

Ben Slade

In the early 1980s, the Bell Telephone Company was convicted of antitrust violations and broken up into several “Baby Bells.” Frequent reorganizations, constant rumors, and a lack of job security took a toll on the workforce. Many employees were overwhelmed by the stress. They experienced physical, mental, and emotional strain at work and at home. However, some employees emerged from the deregulation with an increased sense of energy and vitality. These hardy survivors proceeded to make meaningful contributions both inside the company and out. What distinguished the overachievers from the overwhelmed?

Prolonged or intense stress can put employees at increased risk of illness, marital problems, and reduced productivity. However, some individuals emerge from very stressful events relatively unscathed. Understanding stress vulnerability can help identify opportunities to create pathways to resilience.

One pathway to stress resilience is hardiness. Hardiness has three components: commitment, control, and challenge. Hardy individuals are committed to their organization, finding meaning and stimulation from the work that they do. They believe they can exert control on the world around them, and that their fate is not predetermined. Finally, they interpret difficult experiences as challenges that lead to growth and maturity, and are willing to persist in a difficult environment rather than flee for temporary comfort.

If you are a hardy leader, you will typically excel in stressful circumstances. Although you can sometimes reshape your environment to reduce this stress, you are often surrounded by challenges that are difficult or impossible to change. Your own responses will probably not change the technological limitations, economic recessions, or government regulations that boost your stress levels.

Hardiness is like a rain jacket, deflecting the rain without changing the intensity of the storm. You may not be able to control the environment, but a predisposition towards positive thinking and action can protect you from getting wet. By reframing hard times as an opportunity to excel and conquer, you actually boost your own resistance to stress.

As a leader, your hardiness may even be an umbrella for your team. This hardy leader influence is driven by social sense-making. You can increase your team’s stress resistance with your own behaviors and attitudes.

Transformational leaders inspire and motivate their followers by reframing obstacles as opportunities. Often, you cannot eliminate stress in the workplace. Instead, you can reinterpret stressful circumstances as opportunities to excel. Emotions which can interfere with performance (such as anxiety) can be translated into excitement. When you motivate your team to commit to achievable goals, help them believe that they control their own destiny and demonstrate how obstacles are challenges instead of threats, you have extended your umbrella of hardiness. You bolster individual resilience and improve organizational performance in the face of uncertainty and change.

Do you interpret events in a hardy manner? Do you convey the right messages to your subordinates in the face of uncertainty? You can’t avoid the storms of change, but you can use commitment, control and challenge to help you and your team stay dry.

A Declaration for the Center

Allen Slade

Before my first meeting with Bill Gates, I had every reason to be confident. Microsoft had recently recruited me for my specialized expertise. I had conducted similar meetings with other CEOs. I had a good team behind me, and I had practiced the presentation thoroughly.

The first five minutes went well. Then, Bill asked a question on a minor point. I gave a simple answer, but Bill kept drilling down on the topic. On Bill’s third or fourth question, my confidence evaporated. I was in a full scale amygdala hijack. I needed to quickly reestablish my confidence or the meeting would be a failure.

In Getting to the Center of an Emotional Storm, I suggest centering in the moment as a tool for managing your emotions as a leader. When you are in the spotlight, and your emotions are not serving you well, you can breathe, use a touchstone or make a silent declaration. While declarations can be overplayed by motivational speakers or by comedians (“I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.”), the right declaration can help you manage your emotions. I help my clients find declarations that work, and if declarations don’t work, we focus on other tools for managing emotions.

Declarations help direct our actions. Chalmers Brothers points out how declarations help steer things in the right direction:

For organizations and for individuals, declarations can operate like the rudder of a boat. The boat (organization or person) changes directions as a result of those with authority declaring one thing or another. Declarations are how we identify our priorities and commitments to the future and how we bring certain ways of being into existence (self-worth, well-being, dignity, among others).

For the purposes of managing your own emotions, a compelling personal declaration points you toward a different future. For someone with a fear of public speaking, an effective personal declaration might be: “I will speak with confidence.” This declaration would help moderate anxiety before and during a speech.

The “right” declaration hinges on your personal emotional life and the situation you face. Over the years, my clients have come up with a variety of compelling personal declarations: Stick the landing. Rest my hands. Be confident. Manage my emotions. Re-center. Pause for power. Speak slowly. Build credibility. Make the sale.

Four things will help make a declaration effective in managing your emotions:

Make it simple. Use short, declarative statements.

Make it positive. Don’t use “Don’t . . .” because the stickiness of the last word. “Don’t fidget” focuses the attention on fidgeting, and that will echo in your mind. Stay positive. “Be confident” or “Stick the landing” focuses attention on the new future you are declaring.

Make it powerful. Your declaration must resonate. It must make sense (impacting decision making in your prefrontal cortex) and it must also have emotional weight (impacting emotions in your amygdala).

Make it memorable. Your declaration has to be on the tip of your tongue. Stating your declaration so it is simple, positive and powerful helps. You also need to practice your declaration, starting in safe settings such as your office or with your coach.

So, how did my meeting with Bill Gates turn out? During my amygdala hijack, when my confidence was at its lowest, I centered in the moment. I took a breath, touched my signet ring and said to myself “I am one of the three best people in the world on this topic. You hired me to fix your problems.” I smiled quietly, and re-engaged with confidence.

Getting to the Center of an Emotional Storm

Allen Slade

The oddest thing about hurricanes is the calm at the center of the storm. Pelting rain and destructive winds depart. The wind is calm and the sun is shining. You know the eye won’t last, but you can take a break, step outside, do a quick check and plan how to face the rest of the storm.

Sometimes our emotions swirl like a storm. Today’s post focuses on how leaders can calm their emotions through centering. This is step four of managing emotions:

- “How am I feeling?”

- “How are my emotions serving me right now?”

- “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?”

- “How do I get there?”

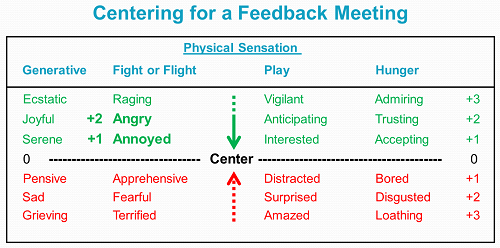

For example, in a feedback meeting with a difficult employee, your fight sensation might be activated. You and your employee would be better served if you have less intense emotions. On the emotional scale below, you don’t want be so intense that you are angry (+2). However, annoyed (+1) would serve you well.

If you decide your emotions are too intense, then how can you move closer to the center? How can you create an eye in an emotional storm?

You can create emotional calm with centering. By focusing your thoughts and calming your body, you can reduce the intensity of your emotions. I use a centering exercise with my clients that takes about five minutes. It can lower your heart rate, reduce your blood pressure and (most importantly) reduce the intensity of your emotions.

You center to reduce your emotional intensity, not to totally bury your emotions. In that feedback meeting with your difficult employee, being completely serene won’t work. You care about performance and you expect to see a change. You want to experience annoyance rather than anger or rage. In general, at work we want emotional intensity of -1 to 1. Emotions at intensity level 2 could be career limiting, except at farewell parties and new product launches.

What if you are in the middle of a meeting when your emotions kick in? It is not possible to close your eyes for five minutes, so you need other tactics to center your emotions.

If someone else is talking, you can center in your chair, Modify your full-length centering exercise so it is shorter. Then, mentally check out of the meeting for 30-60 seconds. Staying seated with your eyes open, run through your routine. Here is one way to center in your chair.

If you are in the spotlight – it is your speech or you have just been called on – you can’t leave for five minutes or check out for 30 seconds. Then, your best move can be to center in the moment by taking a deep breath, touching your touchstone or making a silent declaration.

Breathing. All three exercises – centering, centering in your chair and centering in the moment – involve breathing. Taking a deep, controlled breath oxygenates your blood. This helps lower your pulse, blood pressure and adrenaline. It also establishes, at a visceral level, that you are in control. If one breath doesn’t center you enough, do two more.

Touchstone. A touchstone or totem is something you carry with you to remind you of your purpose and passion. It should have some personal meaning to you. I touch my signet ring. My ring has a custom symbol that reminds me of the important areas of my life – faith, family, friends and work. When I touch it, I remember who I am and what I am about. Your touchstone could be a piece of jewelry, a small stone, or any item that is convenient. The key is that your touchstone should be meaningful to you and should be on you whenever you might face an emotional storm.

Declaration. A centering declaration is a brief, silent statement about your purpose and identity in the form of “I am …” or “I will …” The nature of declarations will be the topic of my next post.

Managing your emotions puts you in charge. You identify your feelings and then deliberately moderate your feelings to serve you and the people around you. Even when your situation is emotionally fraught, you can manage your emotions. You can find the calm you need in the midst of an emotional storm.

The Leader’s Answer to “How Am I Feeling?”

Allen Slade

Emotions are an important part of the leadership landscape. As a leader, you need to be able to manage emotions in yourself and understand the emotions of others. Let’s look at the first step in managing emotions:

- “How am I feeling?”

- “How are my emotions serving me right now?”

- “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?”

- “How do I get there?”

As a leader, how well can you answer the first question? How well can you label your emotions?

Our ability to manage something depends, in part, on our ability to put our observations into words. If you drop me in the Sahara desert with only a water bottle, my ability to describe what I saw would be limited. “Sandy, windy, hot, dry.” I probably would not survive 24 hours without help. The best helper would be someone with the words – “Camel tracks, acacia trees, Tuareg, sirocco” – to make sense of the desert.

Leaders need a rich language of emotion. If your emotional vocabulary is a bit limited, let me suggest two steps to move beyond “sandy and hot” to “acacia and sirocco”. First, you need the words. Then, you need practice using the words.

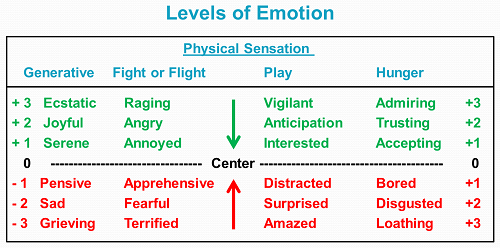

Here is a simple model of emotions from Robert Plutchik. Emotions vary in intensity from +3 to -3. When you are centered, you are at zero for that emotion – it is not actively impacting your behavior or thinking. With four basic physical sensations, there are twenty-four unique emotions.

For most of my clients, this is a great model. If, however, you think of emotions differently, feel free to improvise. Add your own emotions, mix and match. Make sure you label both the type and intensity of your emotions. Otherwise, use whatever matches your emotional life.

For your language of emotion to take hold, you have to put it into practice. Regularly ask yourself “How am I feeling?” Answer with both type of emotion and intensity. Do this whenever you have a substantial event – a meeting, a presentation, a feedback session or a difficult conversation. Also ask yourself periodically throughout the day. It can be helpful to use some way to record your observations, like in this Managing Emotions tool.

The discipline of asking “How am I feeling?” will help you to manage your own emotions. It will also give you greater sensitivity to the emotional landscape around you. You will still find yourself lost in the desert from time to time. But at least you will have the words to make sense of the situation and plot a path to the oasis.