When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Change in Your Personal Leadership Brand

Allen Slade

It is essential for you to have a personal brand statement. I like this style of brand statement:

For [a specific person or group], I want to be known for [six adjectives] so I can deliver [valuable outcomes].

When my clients ask what adjectives they should choose, I respond “What outcomes do you want to deliver?” For my leadership coaching clients, their outcomes usually include maximizing their influence as a leader.

While working on Ford’s employee opinion survey, the CEO wanted to add questions about empowerment. With Ford’s global operations, we delivered the survey in a number of languages. The word “empowerment” proved tricky for many of our translators. In German, the question “My manager understands how to empower people” came back as “My manager understands how to turn on the lights.” I believe in testing my ejection seat, so we found and corrected the mistranslation before the survey went live.

Yet, too many managers focus on turning on the lights – getting the budget set, scheduling activities, communicating basic information, producing management reports. A light switch operator doesn’t really have a personal brand. They are a commodity.

Your impact as a leader is the scope of influence you can exercise. If you can’t drive innovation and growth, you are just turning on the lights. Could you be easily replaced by another manager? If so, you need a new personal leadership brand.

If you wish to be known as a leader and not just an individual contributor or manager, then your personal leadership brand must highlight your ability to innovate/change/grow a team, an organization or a business.

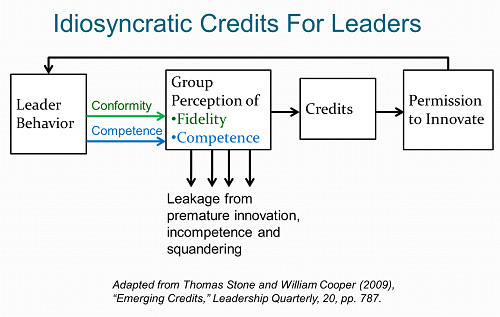

Yet the best leaders do not tilt at windmills like Don Quixote, attempting (and failing) to do the impossible. The best leaders look for difficult challenges that stretch themselves and their team without destroying the leader’s credibility. Thomas Stone and William Cooper capture the tension between innovation and credibility in the following process:

It is a curiosity of leadership that conformity builds credit for future innovation. Going along now creates the opportunity to innovate later. The “leader” who avoids risk does not spend any credits. The leader who pushes too far too fast burns credits without gaining influence.

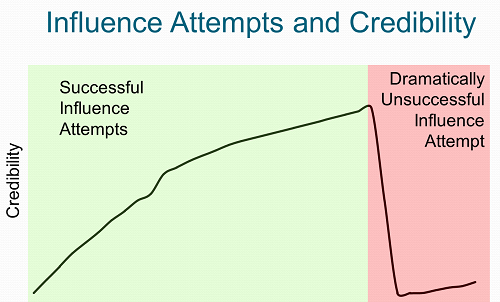

If you are not content with being just a manager, you can change your personal leadership brand. Be patient. Becoming an innovative and influential leader takes repeated success over time. When you first step into a job, you start with a small cache of innovation credits. If you spend those credits wisely, building your group’s perception of your fidelity and competency, you gain more credits. Bit by bit, you are able to innovate more boldly, expanding your influence well beyond the range of indifference. In the image below, this gradual increase in credibility, influence and innovation is captured in the green area.

Since true innovation is risky, you may have a dramatically unsuccessful influence attempt that will erase most of your credibility. In the red area above, the impact of a major misstep leads to a resetting of the credibility curve. Many leaders find it necessary to retreat, operate largely in the range of indifference, until they regain the credibility to tackle new challenges. The loss of credibility can be so severe that the leader needs to start over in a new job or a new organization.

Managers who avoid risk will not play this game. They will stay in the range of indifference, never risking their credibility and hoping to never fail. They may or may not fail, but I can largely guarantee that they will not experience dramatic success.

You have a choice. You can create a personal leadership brand involving wise risk taking to create innovation. Or you can create a safe style more appropriate for a manager. You can empower change, or you can just turn on the lights.

My personal choice was made a long time ago. The Slade & Associates brand is “Creating dialogue and insight for intelligent change.” I hope this blog helps create insight for you that will drive intelligent change in your leadership.

Pivot to the Center

Allen Slade

When incumbent presidents run for re-election, they usually win. Of the last 14 reelection bids, 10 were successful. Since 1996, every president has been reelected. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s perpetual reelection led to a constitutional amendment to limit presidents to two terms.

Non-incumbent politicians must capture the partisan base in the primaries. To win the general election, most politicians have to pivot to the center to capture non-partisan votes. The most effective politicial leaders govern for the common good, usually requiring a second pivot even further to the center.

In this presidential election, Obama was able to stay near the center politically. Romney had to execute a difficult pivot to the center. Jacob Weisberg describes Romney’s campaign as a failed pivot to the center:

Romney is not a right-wing extremist. To win the nomination, though, he had to feign being one, recasting himself as “severely conservative” and eschewing the reasonableness that made him a successful, moderate governor of the country’s most liberal state. . . . Romney’s pandering to the base made it possible for the Obama campaign to portray him as a right-wing radical from the start of the campaign. Fear that he didn’t have the base locked down kept Romney from moving smoothly to the center once he had secured the nomination.

A move to the center is difficult. Politicians who espouse extreme views in the primary but switch to more moderate views for the general election are accused of flip-flopping. They appear to be inauthentic.

As a leader, you have to practice principled moderation. As you advance to functional manager, you have to pivot to center, starting to address issues like budget, efficiency and change management. Many of your former peers will resent you.

If you move from functional manager to general manager, you have to broaden your perspective yet again. You will focus on the bottom line, not just functional excellence. You will balance operations, finance, marketing and human resources. Your peers from your former function will resent you.

These pivots to the center will open you to charges of arrogance, lack of authenticity and selling out. As you pivot to the center, you may appear to be, well, a politician.

To ease your pivot to the center as a leader, I offer three suggestions:

Expand your horizon. You will alienate a few people to serve many people. You will sacrifice your personal comfort to serve the greater good. Just as the best politicians move past partisan appeal to win a general election and govern for the common good, you need to move past beyond a limited perspective and your old peers to lead at the next level. Decide to make the sacrifice before you accept the management position.

Take time for sense-making. A pivot to the center is a major career change. Give yourself time to make sense of the transition.

Get coaching. Get objective, independent advice on how to make a successful pivot to the center. Mentors may help a bit, but coaching is better. Get a leadership coach for the change from technical specialist to functional manager. Get an executive coach for the pivot from functional manager to general manager.

A pivot to the center is one of the toughest moves you can make. Growth and change are always tough, but often rewarding. When you have the opportunity, make your pivot to the center to become the best leader you can be.

Principles of Leadership Are Outdated

Allen Slade

When I teach leadership to business students, I often open the first class by asking students about leaders they respect. Mahatma Gandhi, George Patton, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Steve Jobs are often mentioned. Some students talk about their athletic coach or a former boss.

Then, we get to the heart of leadership. To save you the cost of tuition, here are the highpoints:

The “Great Man” theories of leadership don’t work.

There is no one best way to lead. The best way to lead depends on the situation.

The best leaders are not students of leadership.

There are no simple rules. I discourage imitating role models. I attack leadership trait theories. I undermine leadership style theories. Being the best leader you can be is difficult and complicated.

Those who look for simple answers are understandably disappointed.

Yet, there is a straightforward approach to leadership in my class. Be a student of followership and collect lots of data.

Be a student of followership. Don’t waste time studying leaders or leadership. Study the people you lead. The best leaders have incredible curiosity about the people around them. They ask people what’s important to them, then they think hard about the implications. They check for understanding by asking more questions. The best leaders shape their leadership behavior for their followers.

Collect lots of data. To understand people, the best leaders are hungry for information. They collect data with direct observation of the words, tone and emotions of others. They ask lots of questions. And they suck every bit of value out of any quantitative data they can get, through surveys, 360 reports, attrition data, customer data, etc.

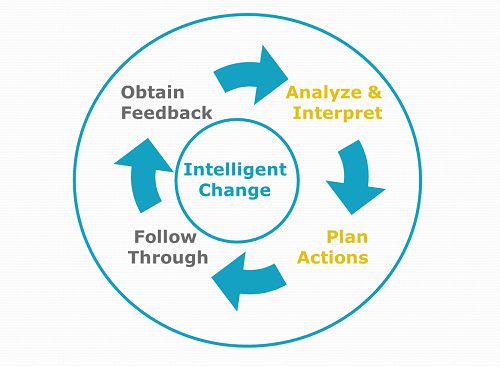

For the visually oriented like me, here is how I capture this vision of leadership:

With a commitment to know the people you lead and a hunger for more data, you can bootstrap your leadership. You can create mini-experiments based on your tentative knowledge of people, and then correct your actions based on their feedback. You will develop a personal, flexible leadership style. And, I suspect, your impact as a leader will expand well beyond what you would achieve if you had simply tried to imitate the great leaders of the past.

The Problem with Problem Solving

Allen Slade

“We have a problem.” If someone says that, do you get a sinking feeling? If you bring up problems with your team, do you feel the energy leave the room?

Let me be clear. Problem solving is good. As a leader, you must solve problems. Your ability to find and fix flaws is essential. Leaders need to find the error, reverse the decline, criticize the fault, hold others accountable and hold difficult conversations.

The problem with problem solving is that we use it too much. Relentless fault finding decreases energy for you and the people around you. If you see everything as a problem, you drain your own energy. If a person frequently finds fault with you, you lose energy for that relationship. If a given task or situation seems to be laden with problems, you lose energy for that task or situation. You may need to continue in that relationship, task or situation, but your heart won’t be in it. Excessive problem solving is a problem.

While problem solving drains energy, appreciation builds energy. As a leader, you must be able to appreciate people and opportunities. You must be able to recognize what is good, true, effective and beautiful. You must reward progress, not just punish shortfalls.

To manage the energy of the people you work with, be mindful of your appreciation ratio. The tipping point seems to be 1/3 problem solving to 2/3 appreciation. When problem solving exceeds 1/3 of interactions, we tend to lose energy for that person, task or situation. When appreciation is 2/3 or more, we tend to build energy. Aim for an appreciation ratio of at least 67%.

Managing my own appreciation ratio has fundamentally changed my outlook on life. I used to see consulting as problem solving. If my client hired me to solve problems, then I had to be scanning for problems, thinking about problems, talking about problems and solving problems. With my problem radar on full power, it is no surprise that I found lots of problems. I completed many consulting assignments thinking “With all these problems, I’m glad I don’t work here.”

Now, I look at my clients from the perspective of success. I look for my client’s strengths – what is good, true, effective and beautiful about what they do. With my appreciation radar on full power, I appreciate my clients more and I project a positive vibe. I still solve problems, but I solve them in an atmosphere of appreciation. Now, when I complete an assignment, I think “This is a great company!”

There is a strategic problem with a low appreciation ratio. Focusing on strategic weaknesses is more than depressing. It is bad strategy. Ford Motor Company got into retail banking in the late 1980s and 1990s. Ford was good at car loans and leasing, but it was not very good at retail banking. A problem solver would work on banking until it was fixed. Ford tried to turn the banks around for a few years , but the company wisely decided to cut its losses and sell the banks. Then, Ford was able to focus on its core competencies in auto financing and manufacturing.

Try a mini-experiment today: focus on what is good, true and effective. Look for strengths more than problems. When you interact with people, notice your appreciation ratio. When it drops below 67%, turn down your problem radar and turn your appreciation radar on full power. In the short term, you will perceive things more positively. In the long term, you will build stronger people, more effective systems and a healthier organization by leveraging competency rather than focusing on failure.

To solve the problem with problem solving, go positive. Problem solve less and there won’t be as many problems. Appreciate more, and you will build your success as a leader.

Are You Just Showing Up?

Allen Slade

You probably had at least one meeting today. Why were you in that meeting? Woody Allen said “90% of life is just showing up.” He’s wrong. Leaders go to meetings to make a difference.

A meeting is like a journey:

You can focus on your next step, looking to avoid a misstep. This short range focus may help you avoid gaffes, but you won’t make much of a difference.

You can think about the next mile – how will we reach our goal for today? With a medium range focus, you can help make today’s meeting a success.

Or you can look to the horizon, and think about where you want to be in the future. With a long range focus, you are looking ahead to future meetings, future decisions and future leadership opportunities. You treat each meeting as an opportunity to grow your influence.

The best leaders do not choose between short, medium and long range focus in a meeting – they do all three at once. They craft a great comment while avoiding gaffes, they make today’s meeting a success and they develop their leadership, all at the same time.

Let’s focus on the long range impact of your meeting participation. As a leader, you should be mindful of your leadership presence in meetings. Do you appear timid? If so, you may not be seen as a leader. Do you talk too much? You may undermine your standing as an empowering leader or an effective team player. Let me suggest three ways you can be mindful of your meeting behavior.

1. If you want to manage your leadership presence in meetings, try noticing how much airtime you take up in meetings.

Airtime is the percent of time you are the focus of the team’s attention (talking, writing on the board, etc.). For a five person team with equal attention, each person should be the focus of attention about a fifth of the time – 20% airtime. A person dominating the conversation has 50% or more airtime.

It is rare that each person gets exactly the same airtime in a meeting. You may have more airtime because your expertise or passion fits the topic.

The point is not to set a specific percentage target. Just notice your airtime.

“Noticing airtime” is not a smart goal. It is not specific, measurable, actionable or time-bound. I am a big fan of smart goals as a powerful source of change, but they are not the only way to develop your leadership. Sometimes just noticing something – being mindful – is all that is needed to trigger a major behavioral change.

2. If the airtime goal doesn’t lead to the change you want, try the rule of three: “I will make 3 valuable contributions in every meeting.” For this to work, you need to do your homework. Study the agenda, do some research, collect some reports and prepare to make a difference.

3. For maximum impact, create a SMART goal. Decide on a plan for your participation in each meeting that is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. For example, “In next Monday’s meeting, I will comment on the product quality topic on the agenda. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story. I will practice using both the data and the story with my coach before the meeting. I will use the data, the story or both in the meeting.”

See each meeting as a leadership development opportunity. Stay focused to make a difference. Avoid missteps, push the decision ahead and grow your leadership all at the same time.

Leading in Stormy Weather

Ben Slade

In the early 1980s, the Bell Telephone Company was convicted of antitrust violations and broken up into several “Baby Bells.” Frequent reorganizations, constant rumors, and a lack of job security took a toll on the workforce. Many employees were overwhelmed by the stress. They experienced physical, mental, and emotional strain at work and at home. However, some employees emerged from the deregulation with an increased sense of energy and vitality. These hardy survivors proceeded to make meaningful contributions both inside the company and out. What distinguished the overachievers from the overwhelmed?

Prolonged or intense stress can put employees at increased risk of illness, marital problems, and reduced productivity. However, some individuals emerge from very stressful events relatively unscathed. Understanding stress vulnerability can help identify opportunities to create pathways to resilience.

One pathway to stress resilience is hardiness. Hardiness has three components: commitment, control, and challenge. Hardy individuals are committed to their organization, finding meaning and stimulation from the work that they do. They believe they can exert control on the world around them, and that their fate is not predetermined. Finally, they interpret difficult experiences as challenges that lead to growth and maturity, and are willing to persist in a difficult environment rather than flee for temporary comfort.

If you are a hardy leader, you will typically excel in stressful circumstances. Although you can sometimes reshape your environment to reduce this stress, you are often surrounded by challenges that are difficult or impossible to change. Your own responses will probably not change the technological limitations, economic recessions, or government regulations that boost your stress levels.

Hardiness is like a rain jacket, deflecting the rain without changing the intensity of the storm. You may not be able to control the environment, but a predisposition towards positive thinking and action can protect you from getting wet. By reframing hard times as an opportunity to excel and conquer, you actually boost your own resistance to stress.

As a leader, your hardiness may even be an umbrella for your team. This hardy leader influence is driven by social sense-making. You can increase your team’s stress resistance with your own behaviors and attitudes.

Transformational leaders inspire and motivate their followers by reframing obstacles as opportunities. Often, you cannot eliminate stress in the workplace. Instead, you can reinterpret stressful circumstances as opportunities to excel. Emotions which can interfere with performance (such as anxiety) can be translated into excitement. When you motivate your team to commit to achievable goals, help them believe that they control their own destiny and demonstrate how obstacles are challenges instead of threats, you have extended your umbrella of hardiness. You bolster individual resilience and improve organizational performance in the face of uncertainty and change.

Do you interpret events in a hardy manner? Do you convey the right messages to your subordinates in the face of uncertainty? You can’t avoid the storms of change, but you can use commitment, control and challenge to help you and your team stay dry.

What to Expect from Leadership Coaching

Allen Slade

Gifts can be a source of joy or a nasty surprise. If your company provides you a leadership coach, how should you react? Heartfelt delight or muted disappointment? Is leadership coaching the perfect gift for you? Or is it the ugly sweater?

Leadership coaching is a powerful gift when it works as designed. Coaching increases your ability to achieve results and build healthy relationships. It helps you stretch into your best self as a leader.

A talented and wise coach (preferably accredited) will help you stretch into your best self. The coaching conversation can be the high point of your week. Your coach’s insightful listening and powerful questions can trigger new insights into your leadership. The best coaches assume that you are the expert on your own situation. Your coach will draw out your expertise through inquiry, curiosity and gentle challenges. The mini-experiments you design together can lead to breakthroughs in your influence and your presence as a leader.

Leadership coaching comes in different flavors:

Coaching for achievement maximizes your performance in your current role. The leader wants to move from good to great. Your leadership coach will help you focus on the behaviors and thinking necessary to supercharge performance. For achievement coaching to have maximum value, you need to have already learned the ropes. That means 6 months or more in your current job.

Coaching in transition helps you adjust to a new role so you can have a fast start. Your coach will help you learn the ropes – making sense of your new role. Rapid sense-making will help you adjust your behavior, thinking and expectations to accelerate maximum performance in your new role. Transition coaching may start before, during, or soon after the leader has moved into a new role. Sometimes, recruiting firms will provide a leadership coach to ensure that the placement has the greatest odds of success.

Coaching in crisis is designed to turn around an unsuccessful situation. The leader’s performance is unacceptable in one or more ways, and the leader and the organization want to improve the situation. Successful crisis coaching requires the leader, HR and the leader’s manager to agree to have mutual candor, commitment to change and the expectation that things can improve.

When can the gift of coaching turn out to be an ugly sweater? One example is coaching in crisis when the organization has already decided to end the leader’s employment. Another example is when the leader’s confidentiality is violated.

Most ICF accredited coaches take steps to avoid these situations. If no turnaround is possible, Slade & Associates does not offer coaching in crisis. (However, if the leader’s employment is at an end, we gladly offer career coaching as part of outplacement packages.) We always require a written agreement of strict confidentiality. Our approach to leadership coaching safeguards our dialogue, maximizes your insight and drives intelligent change for your organization.

Leadership coaching is an incredible benefit. If your organization offers you a leadership coach, accept the gift gladly. Check on the coach’s credentials. Make sure your coach, your organization and you agree on the purpose of the coaching. Demand coaching confidentiality. Then, prepare to be surprised and delighted as you unwrap the insights and wisdom of leadership coaching.

The Leader’s Tipping Point

By Allen Slade

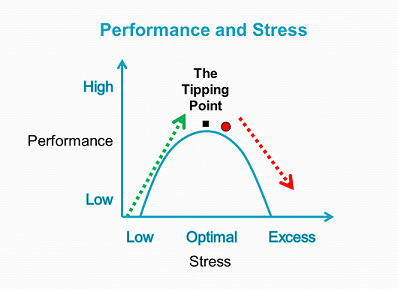

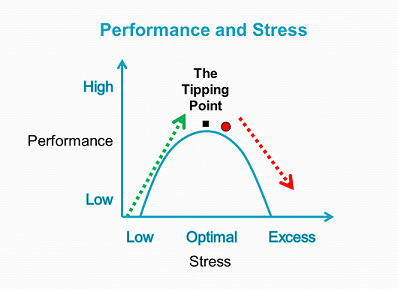

Leadership is about creating sustainable performance in your team. Jim Clawson points out that effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a post on The Tipping Point of Performance, I talked about managing energy in others to create sustainable performance. As a leader, you have a proven track record of results. You combine competence, capacity and committent to success, so people are willing to follow you. But is your performance sustainable?

Bottom line: As a leader, you have to manage your own energy. Know your performance curve, watch for signs of an impending performance crisis and take dramatic action as needed.

The performance curve is just as true for you as it is for the people you lead. We all experience this inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between your level of stress and your performance holds, but only in the green zone.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

Bottom line: Push youself, but know your own tipping point. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Manage your own stress wisely, especially on the dangerous part of the performance curve.

Stress reduction strategies. Whether you are at the top of the green zone or at the tipping point, try stress management strategies. Simplify your life. Practice centering. Off load non-essential work. Get help from your boss, in terms of more people, more resources or more time. Ask your colleagues for support. Delegate to your team.

Develop yourself. Long-term, grow your capacity for performance to avoid a stress-induced performance crisis. Develop new skills. Practice skills to the point of mastery. Practice for speed, not just completion. If you can write methodically, practice writing under a deadline. (Blogging three times a week is speeding up my writing!) Coaching can help, whether you are an executive, leader or golfer. At Slade & Associates, we coach executives and leaders to maximize their performance. There are certain things we don’t do, so you would do well to find your own golf coach.

Your urgency in reducing your stress depends on your position on the performance curve:

Top of the green zone. If you push harder but don’t see much improvement, you may be approaching the top of your green zone. Be careful, because you could hit your tipping point. Be alert for further stress, and consider strategies to reduce stressors or increase your performance capacity.

The tipping point. Approaching your tipping zone is dangerous. If familiar tasks become harder, if your inbox is overwhelming, if you snap at reasonable requests or if you work longer with fewer results, you may be at your tipping point. At the tipping point, you still have time. You can think. You can experiment with one stress reducer at a time. Take action now to reduce your stress. Climb back down into the green zone while you can still think clearly.

The red zone. Passing your tipping point is catastrophic because of the accelerating downward spiral of performance. To get out of the red zone, aggressively implement stress management strategies. Make a plan that combines at least two or three big stress reducers – simplify, center, get support from your boss, delegate, etc. Make smart requests ask your boss for support or delegate. Whatever the details, take dramatic action. In the red zone, you must act now.

A lifeguard. I must confess: This red zone advice may not work. The downward spiral of performance undermines your decision making and behavioral flexibility. If you are drowning, sometimes you can’t save yourself. You need a lifeguard who will know you need help and step in during a crisis. Your lifeguard could be a friend, a mentor, a coach or your family. Before a red zone crisis, build strong relationships. Be transparent, accountable and open to constructive feedback. Then, if you are drowning in stress, you will have someone willing to dive in to save you.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for yourself and for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

The Tipping Point of Performance

Allen Slade

I love sports movies, especially about underdogs. The critical moment is when the coach or loved one gets the underdog fired up. I love Rocky II, when Talia Shire lights Rocky’s fuse from her hospital bed and Remember the Titans, when Denzel Washington gives a moving call for unity in the Gettysburg cemetery.

As a leader, do you try to fire up your team? Be careful. If you play with fire, you can get burned.

Clearly, there are times when you need to establish a sense of urgency. But asking for extraordinary effort can backfire. As the performance curve below shows, there is an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between stress and performance does hold, but only in the green zone.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

The problem hits at the top of the curve. When a person reaches the tipping point, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance leads to a downward spiral in the red zone. People become anxious. They act indecisively, work slower or make more mistakes. As their performance decreases, their anxiety increases, further decreasing their performance. Notice the red marble at the top of the performance curve. In the red zone, the marble accelerates down the curve of poor performance. As a leader, if you push a person too far, their performance drops. And, their performance will continue to get worse because of the downward spiral.

Bottom line: Push for performance, but avoid the tipping point for stress. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Aim for high performance, not peak performance. I coach leaders to avoid pushing people to their tipping point. If the tipping point is at 100% performance, aim for 90 or 95%. Then, your team member has a stress buffer. If there is a coffee spill that wipes critical data or a car wreck going to the big meeting, they will have the psychological reserves to get through it. If you push to get the full 100%, your people may tip into the red zone.

Develop your people. If you wish to increase performance, but a person is near the tipping point, think development first, motivation later. Increase their competence and capacity, so they can perform better while maintaining an essential stress buffer.

Be a lifeguard. Your people can drown in stress. The downward spiral of performance undermines decision making and behavioral flexibility. If someone is in the red zone, you may need be their lifeguard. Watch for signs of stress in your team members, watching for people at the tipping point or in the red zone. Then, throw them a life line. Offer more resources, renegotiate deadlines, offer them time off to refresh and rest. Be creative – think of the rousing speech that fires up the underdog, then do the opposite.

Know your team. Everyone is different. The people you lead have different capabilities and stress tolerances. They will show different warning signs of a stress-induced performance crisis. Get to know your people before a crisis. Have regular dialogue with every team member. Seek insight about their performance patterns, personal stressors and individual signs of overload. This will equip you to be a stress lifeguard.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

Negotiation: The Dance of Requests and Offers

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Requests and offers make up the dance of negotiation. An offer is the mirror image of a request. With a request, you are triggering action by the other person. With an offer, you are proposing to act for the other person. An offer requires a valid response, just like a request: Yes, No, Counter Offer or Decide Later. It is the back and forth of requests paired with offers and offers followed by counter offers that creates the dance of negotation.

A succesful negotiation leads to an agreement that meets the interests of both you and the other person. Bill Ury distinguishes several forms of negotiation:

Hard positional bargaining. “Participants are adversaries. The goal is victory. Demand concessions as a condition of the relationship. Distrust others. Dig in to your position. Make threats.”

Soft positional bargaining. “Participants are friends. The goal is agreement. Make concessions to cultivate the relationship. Trust others. Change your position easily. Make offers.”

Positional bargaining, hard or soft, locks in positions and makes the negotation a win-lose game. Positional bargaining tends to produce unwise agreements, inefficiency in the bargaining process and stress in an ongoing relationship. I have purchased a number of cars using hard positional bargaining. Even if we reach an agreement, the bargaining is adversarial, long and dissatisfying, at least for me as a customer.

Principled negotiation is when the parties go beyond positions to the underlying interests and look for win-win solutions. Four steps will help you do this:

- People: Separate the people from the problem.

- Interests: Focus on interests, not positions.

- Options: Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do.

- Criteria: Insist that the results be based on some objective standard.

I use principled bargaining to buy and sell cars. For my last car purchase, I looked for a dealer who would agree to principled negotiation. Over the phone, we agreed to use a price that was $250 over dealer cost. The face-to-face negotiation was amicable, efficient and mutually satisfactory.

Is principled negotiation better to hard or soft bargaining? It depends. I keep all three forms of bargaining in my leadership tool box. I tend to use principled negotiation in ongoing relationships dealing with a substantive issue. Negotiating on principles builds relationships while building agreements. I may use hard positional bargaining when there is no long term relationship and the other person is treating the situation as a win-lose game. I may use soft positional bargaining when the relationship is key, the other person is passionate about their position and I am flexible on the issue.

If you practice the steps of requests and offers, you will be able to dance to a variety of music. Make smart requests. Make big asks. Give and demand valid responses. You can adjust your negotiation style to the heavy metal of hard positional bargaining, the swing dancing of soft positional bargaining or the long term romantic dance of positional bargaining. If you influence the play list, you may be able to set the style of negotiation you prefer. Otherwise, negotiate to the music being played.