When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

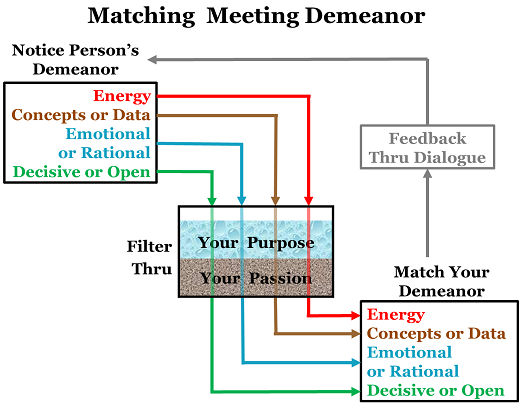

Leadership Tools: Matching Meeting Demeanor

Allen Slade

Leaders need a toolbox full of tools for task leadership (budgeting, scheduling, goal setting, task execution) and relationship building(communication, decision making techniques, empathy). To use these leadership tools well, you need to diagnose the situation before you pick your tool.

A coaching client asked me “How should I act?” in an important meeting. I suggested matching his confidence to his competence and matching his demeanor to the other person. Let’s look at how “demeanor matching” works.

Often, leaders are called upon to persuade someone to take action. You might be planning with your boss, problem solving with an employee, trying to close a sale or interviewing for a job. It’s important to focus on the content of the meeting, but your influence will be determined by the tone of the meeting. How do you get your demeanor right?

Consider four dimension of meeting demeanor:

- High energy vs. low energy.

- Concrete data vs. abstract concepts.

- Rational persuasion vs. emotional persuasion.

- Decisive choices vs. option multiplying.

If two people are badly mismatched on any of these dimensions, the meeting will not go well.

We have all been held hostage in meetings. The other person is not on your wavelength and they are clueless about their lack of influence. They are high energy while you are drifting off. Maybe they offer abstract concepts when you need hard data. Or they make an emotional appeal when you want a rational argument. They push for decisive action when you want to keep your options open.

To avoid holding others hostage in a pointless meeting, don’t be tone deaf. Start by noticing the other person’s demeanor, then decide how your meeting demeanor needs to adjust.

Energy. If they have little energy for this topic, don’t try to bulldoze them. Take a low key approach. Pause, contemplate, listen even more than usual. But if they have high energy, ramp up your excitement to match.

If your purpose is to pursuade them, you may have to go against your native personality. Extroverts may have to calm down. Introverts may need to get fired up.

Concepts/data. If their conversation centers around concepts, principles, precedents, fairness – respond in kind. If they ask for data, proof, evidence, case studies, give them the numbers and facts they need.

Once again, you may be more conceptual or more data oriented, but don’t let that undermine your effectiveness if the other person is on a different wavelength.

Emotional arguments or rational arguments. Listen and observe. If they say or act in a way that suggests they want to approach this topic through an emotional lens, paint your argument with the colors of feeling. If they want to argue, respond with logic.

The “emotional intelligence” industry is built on the failings of leaders who think it is irrational to be emotional. You can also fail with feelings when the other person wants logic. Either way, if your purpose is to persuade, you may have to step outside your native logic to match their meeting demeanor.

Decisive or open. Sometimes, the other person wants to decide now. Other times, they want more options, more evidence or more people involved.

If you are naturally decisive but they want more time, you may need to practice patience. If you tend to keep your options open but the other person expresses impatience, you may need to work toward a “best guess” decision.

Bottom line: Effective leaders are versatile in their meeting demeanor. They use high energy or calmness, concepts or data, feelings or logic, decisiveness or patience, as needed to fulfill their purpose in the meeting.

In your next meeting, try noticing the demeanor of the other person. Then notice your own demeanor. Adjust as needed to be at your most influential.

Leadership Tools: Confidence

Allen Slade

Effective leadership requires adaptability. Leaders should fill their leadership toolbox and then pick the right tool for the situation. In other words, match your behavior to the task at hand.

Last week, a coaching client preparing for a one-on-one meeting asked “How should I act?” Because principles of leadership are outdated, I didn’t give a one-size fits all answer. Instead, I suggested two ways to match his behavior to the situation: Match your confidence to your competence (today’s topic). Your demeanor should match the other person’s demeanor (in the next post).

As a leader, your confidence is a tool. You should be able to influence others based on your experience, your expertise or your position of authority. But like any tool, you can misuse your confidence.

Overconfidence is a common leadership failing. If you choose to act confident, make sure you have the competence to back it up. If all you own is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If your leadership “style” is always high confidence, you will hammer decisions and people. Don’t be that leader.

Lack of confidence is another leadership failing. If you act like you do not know, you will undermine your leadership. If you don’t act like a confident leader, no one will want to follow you.

Even moderate confidence has drawbacks. “Powerful but approachable” or “humble yet decisive” may be desirable blends, but there are times when very high confidence (or very high humility) would be better than a compromise.

Sticking with one level of confidence – high, low or in between – would be leading on cruise control. Instead, match your confidence to your competence.

Suppose you face a high stakes technical decision. How can you match your confidence to your competence?

If you are a novice in the technology, listen and learn. Ironically, you can build credibility by complying with others. Save your confidence for situations where you know what you are talking about.

If you know about as much as the others in the room, engage in a good give and take. Bring your competence to bear, but don’t be overbearing. Admit the limits of your expertise and experience. Value the competence of others.

If you are highly competent to deal with this issue, you can show analytical strength and make hard-hitting recommendations. But even as the most competent person in the room, treat your confidence as a tool rather than a trait. At times, put confidence back in the toolbox to pull out other tools like listening or consensus building.

Bottom line: Treat confidence like a tool rather than a trait. Match your confidence to the situation to maxmize your credibility and influence.

Using the Tools of Leadership

Allen Slade

As a leader, it is not enough to have the job title. At the point of action, you need to choose the right tool for the job.

Leaders can’t operate on cruise control. Instead, they should will fill their leadership toolbox with a variety of tools: Task and person leadership. A variety of communication techniques. A range of decision making approaches. Verbal, quantitative and emotional intelligence. Macro and micro perspective. Fast or slow action. Problem solving and paradox managing.

But you can mess up, even with a full toolbox. At the point of choice, you need to know which leadership tool to pick up. If you pick up a circular saw to cut hard to reach nails, don’t expect it to go well.

But you can mess up, even with a full toolbox. At the point of choice, you need to know which leadership tool to pick up. If you pick up a circular saw to cut hard to reach nails, don’t expect it to go well.

There is no simple how-to guide for leadership. While Amazon lists 86,941 books on leadership (and probably more by the time you read this post), be careful. The reality you face is more complex and subtle than obeying leadership laws or imitating newsworthy leaders.

Bottom line: You need to develop your own leadership insight through experience and the wisdom of others.

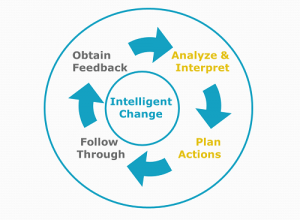

Leadership insight starts with personal experience. As you develop the ability to use a leadership tool, you will start to develop a sense of when that tool is the best choice. Maximize your growth by taking an intelligent change approach to your leadership experience.

Risk-taking. Leadership insight starts with action – what’s called follow through in our intelligent change model. Excessive perfectionism will keep your shiny new tool in the box.

Risk-taking. Leadership insight starts with action – what’s called follow through in our intelligent change model. Excessive perfectionism will keep your shiny new tool in the box.

Feedback. Experience-based learning happens only with feedback. You need to know how the tool worked to know when to use it.

Reflection. It is not enough to experiment and to collect feedback. You must analyze and interpret your experience. Contemplating the what, how and (especially) the when of your successes and failures will help you figure out when to choose a leadership tool. To be accountable for reflecting on your leadership, try keeping a leadership journal or chat with your circle of trusted advisers on a regular basis.

The wisdom of others. You learn faster with help. Teachers, mentors and coaches are all valuable resources to help you figure out your personal theory of leadership. As leaders mature, they learn less from the expertise of teachers or the experience of mentors. From mid-career on, leadership growth requires finding your own leadership coach or executive coach. Ask your senior leader or HR person if your company can provide a coach for you.

Fill your leadership toolbox and develop your insight so you know what works. Then, you will be ready to grab the right tool for the situation.

The Leader’s Toolbox

Allen Slade

Before rebuilding our friends’ deck, I loaded my van with tools: 3 power saws, 4 drills, 3 measuring squares and a bucket full of hand tools. Why so many tools? Wouldn’t one saw be enough? The circular saw cuts fast and straight, but isn’t maneuverable. The sabre saw cuts straight or curved, but slow. The reciprocating saw is for demolition – maneuverable but leaves a jagged cut. The third measuring square was unnecessary, but every other tool was used repeatedly.

In Leading on Cruise Control, I suggested that the best leaders adjust to the conditions they face. As a leader, you need a variety of leadership tools and the ability to diagnose what tool is needed for the situation at hand. But tools come before diagnostic skill. If all you own is a hammer, then everything looks like a nail. Here is a partial list of tools that should be in every leader’s toolbox.

Task and Person Leadership. The ability to focus on task leadership – resource allocation, project management, goal setting and execution. And, the ability to build strong and mutually beneficial relationships.

Communication. One-on-one, small group and large group. Rhetorical persuasion, information sharing, story telling and listening. Requests, offers, negotiations, declarations and assessments. Management by walking around and the ability to influence from a distance.

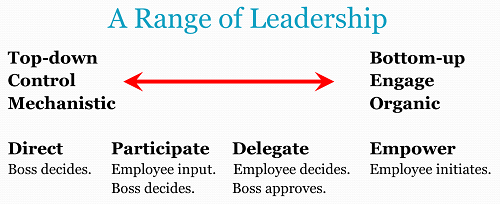

Decision Making. Data-driven or political decisions. Optimizing or satisficing. The full range of employee involvement – Direction, participation, delegation or empowerment.

Fast and Slow. Strategic thinking and instinctive reaction. The ability to do exhaustive, multi-disciplinary long-range planning and the ability to leap before you look.

Intelligence. Verbal, quantitative and emotional intelligence. The ability to see the big picture and to edit the pixels. The ability to solve problems and to manage paradoxes. Principled moderation.

How do you add tools? Start treating every day as a leadership laboratory. Do many mini-experiements and get lots of feedback. Take every opportunity to try the new and different. Communicate differently – new groups, new approaches, new technology. Take every class you can.

Longer term, take on big challenges. Get another degree. Take on stretch assignments. Switch functions. Switch careers. Cross cultures.

For an emerging leader, this list can be overwhelming. Be patient. It takes time to fill your toolbox.

For an emerging leader, this list can be overwhelming. Be patient. It takes time to fill your toolbox.

For a senior leader, you have many of these tools already. Don’t be satisfied. For the deck project, I could use a miter saw for the trim. Keep adding leadership tools.

How full is your leader’s toolbox? Don’t try to lead with duct tape and a pair of vice grips. Get the tools to do the job right.

Leading on Cruise Control

Allen Slade

One of the great conveniences of driving is cruise control. You can take your foot off the gas pedal and the car maintains speed. I recently drove 400 miles in a car without cruise control – in the rain, after a long day – and I was miserable.

For leaders, cruise control is also handy. You develop a leadership style that works. You build on past success. You lead with policies, procedures and patterns. You can drive the organization with relative ease, even in the rain after a long day.

There is a minor problem with leading on cruise control. You will not lead very well. As Skinner and Sasser conclude:

Managers who consistently accomplish a lot are notably inconsistent in their manner of attacking problems. They continually change their focus, their priorities, their behavior patterns with superiors and subordinates, and indeed, their own “executive styles.” In contrast, managers who consistently accomplish little are usually predictably constant in what they concentrate on and how they go at their work. Consistency . . . is indeed the hobgoblin of small and inconsequential accomplishment.

The best leaders, like the best drivers, adjust to the conditions they face. They know faster change is their only advantage, and they go slow to go fast. The best leaders can give the rousing speech, they can hold the quiet conversation and they can listen. The best leaders shift decision styles. They use the full range of leadership: direction, participation, delegation or empowerment.

Bottom line: The best leaders do not lead on cruise control. They adjust their leadership to the needs of the moment. They are versatile. They are inconsistent in order to gain consistently great results.

How versatile are you as a leader? Do you need a greater range of speed and style? Two suggestions:

Create a leadership scorecard to unlock your habits with data and reprogram your behavior.

Find out if your organization will provide you a leadership coach or an executive coach to help you identify opportunities to increase your flexibility.

Permanently disable your leadership cruise control. Lead according to the situation. It may be less comfortable, but you will be a better leader.