When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Developing Your Personal Brand

When you walk in the room, who shows up for the other people? Is how you perceive yourself the same as how others perceive you? In this 35 minute video, Allen Slade shows how to develop a personal brand strategy so you can become influential and be effective.

A Declaration for the Center

Allen Slade

Before my first meeting with Bill Gates, I had every reason to be confident. Microsoft had recently recruited me for my specialized expertise. I had conducted similar meetings with other CEOs. I had a good team behind me, and I had practiced the presentation thoroughly.

The first five minutes went well. Then, Bill asked a question on a minor point. I gave a simple answer, but Bill kept drilling down on the topic. On Bill’s third or fourth question, my confidence evaporated. I was in a full scale amygdala hijack. I needed to quickly reestablish my confidence or the meeting would be a failure.

In Getting to the Center of an Emotional Storm, I suggest centering in the moment as a tool for managing your emotions as a leader. When you are in the spotlight, and your emotions are not serving you well, you can breathe, use a touchstone or make a silent declaration. While declarations can be overplayed by motivational speakers or by comedians (“I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.”), the right declaration can help you manage your emotions. I help my clients find declarations that work, and if declarations don’t work, we focus on other tools for managing emotions.

Declarations help direct our actions. Chalmers Brothers points out how declarations help steer things in the right direction:

For organizations and for individuals, declarations can operate like the rudder of a boat. The boat (organization or person) changes directions as a result of those with authority declaring one thing or another. Declarations are how we identify our priorities and commitments to the future and how we bring certain ways of being into existence (self-worth, well-being, dignity, among others).

For the purposes of managing your own emotions, a compelling personal declaration points you toward a different future. For someone with a fear of public speaking, an effective personal declaration might be: “I will speak with confidence.” This declaration would help moderate anxiety before and during a speech.

The “right” declaration hinges on your personal emotional life and the situation you face. Over the years, my clients have come up with a variety of compelling personal declarations: Stick the landing. Rest my hands. Be confident. Manage my emotions. Re-center. Pause for power. Speak slowly. Build credibility. Make the sale.

Four things will help make a declaration effective in managing your emotions:

Make it simple. Use short, declarative statements.

Make it positive. Don’t use “Don’t . . .” because the stickiness of the last word. “Don’t fidget” focuses the attention on fidgeting, and that will echo in your mind. Stay positive. “Be confident” or “Stick the landing” focuses attention on the new future you are declaring.

Make it powerful. Your declaration must resonate. It must make sense (impacting decision making in your prefrontal cortex) and it must also have emotional weight (impacting emotions in your amygdala).

Make it memorable. Your declaration has to be on the tip of your tongue. Stating your declaration so it is simple, positive and powerful helps. You also need to practice your declaration, starting in safe settings such as your office or with your coach.

So, how did my meeting with Bill Gates turn out? During my amygdala hijack, when my confidence was at its lowest, I centered in the moment. I took a breath, touched my signet ring and said to myself “I am one of the three best people in the world on this topic. You hired me to fix your problems.” I smiled quietly, and re-engaged with confidence.

Getting to the Center of an Emotional Storm

Allen Slade

The oddest thing about hurricanes is the calm at the center of the storm. Pelting rain and destructive winds depart. The wind is calm and the sun is shining. You know the eye won’t last, but you can take a break, step outside, do a quick check and plan how to face the rest of the storm.

Sometimes our emotions swirl like a storm. Today’s post focuses on how leaders can calm their emotions through centering. This is step four of managing emotions:

- “How am I feeling?”

- “How are my emotions serving me right now?”

- “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?”

- “How do I get there?”

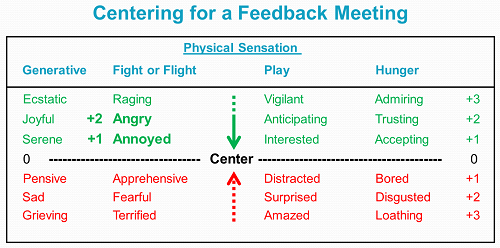

For example, in a feedback meeting with a difficult employee, your fight sensation might be activated. You and your employee would be better served if you have less intense emotions. On the emotional scale below, you don’t want be so intense that you are angry (+2). However, annoyed (+1) would serve you well.

If you decide your emotions are too intense, then how can you move closer to the center? How can you create an eye in an emotional storm?

You can create emotional calm with centering. By focusing your thoughts and calming your body, you can reduce the intensity of your emotions. I use a centering exercise with my clients that takes about five minutes. It can lower your heart rate, reduce your blood pressure and (most importantly) reduce the intensity of your emotions.

You center to reduce your emotional intensity, not to totally bury your emotions. In that feedback meeting with your difficult employee, being completely serene won’t work. You care about performance and you expect to see a change. You want to experience annoyance rather than anger or rage. In general, at work we want emotional intensity of -1 to 1. Emotions at intensity level 2 could be career limiting, except at farewell parties and new product launches.

What if you are in the middle of a meeting when your emotions kick in? It is not possible to close your eyes for five minutes, so you need other tactics to center your emotions.

If someone else is talking, you can center in your chair, Modify your full-length centering exercise so it is shorter. Then, mentally check out of the meeting for 30-60 seconds. Staying seated with your eyes open, run through your routine. Here is one way to center in your chair.

If you are in the spotlight – it is your speech or you have just been called on – you can’t leave for five minutes or check out for 30 seconds. Then, your best move can be to center in the moment by taking a deep breath, touching your touchstone or making a silent declaration.

Breathing. All three exercises – centering, centering in your chair and centering in the moment – involve breathing. Taking a deep, controlled breath oxygenates your blood. This helps lower your pulse, blood pressure and adrenaline. It also establishes, at a visceral level, that you are in control. If one breath doesn’t center you enough, do two more.

Touchstone. A touchstone or totem is something you carry with you to remind you of your purpose and passion. It should have some personal meaning to you. I touch my signet ring. My ring has a custom symbol that reminds me of the important areas of my life – faith, family, friends and work. When I touch it, I remember who I am and what I am about. Your touchstone could be a piece of jewelry, a small stone, or any item that is convenient. The key is that your touchstone should be meaningful to you and should be on you whenever you might face an emotional storm.

Declaration. A centering declaration is a brief, silent statement about your purpose and identity in the form of “I am …” or “I will …” The nature of declarations will be the topic of my next post.

Managing your emotions puts you in charge. You identify your feelings and then deliberately moderate your feelings to serve you and the people around you. Even when your situation is emotionally fraught, you can manage your emotions. You can find the calm you need in the midst of an emotional storm.

The Leader’s Answer to “How Am I Feeling?”

Allen Slade

Emotions are an important part of the leadership landscape. As a leader, you need to be able to manage emotions in yourself and understand the emotions of others. Let’s look at the first step in managing emotions:

- “How am I feeling?”

- “How are my emotions serving me right now?”

- “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?”

- “How do I get there?”

As a leader, how well can you answer the first question? How well can you label your emotions?

Our ability to manage something depends, in part, on our ability to put our observations into words. If you drop me in the Sahara desert with only a water bottle, my ability to describe what I saw would be limited. “Sandy, windy, hot, dry.” I probably would not survive 24 hours without help. The best helper would be someone with the words – “Camel tracks, acacia trees, Tuareg, sirocco” – to make sense of the desert.

Leaders need a rich language of emotion. If your emotional vocabulary is a bit limited, let me suggest two steps to move beyond “sandy and hot” to “acacia and sirocco”. First, you need the words. Then, you need practice using the words.

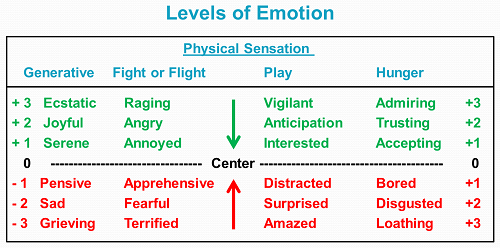

Here is a simple model of emotions from Robert Plutchik. Emotions vary in intensity from +3 to -3. When you are centered, you are at zero for that emotion – it is not actively impacting your behavior or thinking. With four basic physical sensations, there are twenty-four unique emotions.

For most of my clients, this is a great model. If, however, you think of emotions differently, feel free to improvise. Add your own emotions, mix and match. Make sure you label both the type and intensity of your emotions. Otherwise, use whatever matches your emotional life.

For your language of emotion to take hold, you have to put it into practice. Regularly ask yourself “How am I feeling?” Answer with both type of emotion and intensity. Do this whenever you have a substantial event – a meeting, a presentation, a feedback session or a difficult conversation. Also ask yourself periodically throughout the day. It can be helpful to use some way to record your observations, like in this Managing Emotions tool.

The discipline of asking “How am I feeling?” will help you to manage your own emotions. It will also give you greater sensitivity to the emotional landscape around you. You will still find yourself lost in the desert from time to time. But at least you will have the words to make sense of the situation and plot a path to the oasis.

Emotional Intelligence is Dumb

Allen Slade

There is a problem with emotional intelligence. “Intelligence” implies an upper limit on competence. Emotional intelligence, at its worst, implies you can’t exceed your native ability.

Intelligence tests were originally designed to place children into limited academic tracks. At Riverside Elementary School, we had four tracks. At the age of 12, I was placed into the lowest track, designed for students who did not have the intellectual ability to go to college. I decided to prove the school wrong. For every question by the teacher, I was the first to raise my hand. I worked for perfection on every assignment. I helped other students master the material. Because of my efforts, I earned the nickname of “The Professor”. Something fundamentally changed in me during that year. I went to college and stayed for a while. At the age of 28, I was called professor again. But this time it was by my management students at the University of Delaware.

Tracking students based on intelligence tests may or may not be a good education strategy. Limiting your leadership based on “emotional intelligence” is just plain dumb.

What is smarter than emotional intelligence? I prefer to talk about managing emotions. Management – of organizations, projects or emotions – can be learned and mastered. Our emotional competence is virtually unlimited. As a leader, you can get better at understanding and shaping your own emotions. You can get better at understanding the emotional landscape – the patterns and peaks of the people around you. You can master the art of managing emotions.

When life happens, managing emotions consists of four steps:

1. “How am I feeling?” Ask this regularly. Ask this question when you are blocked, when you can’t think straight or when you are shaking. Ask it before the big meeting, before the difficult conversation, before the Big Ask. Ask it when you are surprised by life’s events. If you want to develop your emotional competence, I recommend using an emotional log. Regularly ask “How am I feeling?” and then record their observations. An emotional log helps you master monitoring of your emotions.

2. “How are my emotions serving me right now?” If your emotions are serving you well, continue on.. If your emotions are not serving you well, ask yourself:

3. “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?” Are you too intense? Too flat? Are you experiencing fear (flight response) when anger (fight response) would serve you better?

4. “How do I get there?” For more moderate emotions, you can center or take a deep breath. For different emotions or for more intense emotions, you can silently declare your desired future to yourself. Since you are the most credible person you know, you can probably persuade yourself. You can touch an object or totem to remind yourself of your purpose and passion.

Two weeks ago, I was preparing for a radio interview on managing emotions. About 20 minutes before we went on air, I noticed my writing was wobbly and my voice had a slight tremor. I reflexively went through the four steps: 1. How am I feeling? Nervous, excited. 2. How are my emotions serving me right now? I will sound nervous on air, undermining what I hope to communicate. 3. Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better? Yes. The type of emotions are appropriate, but they are too intense. I like to have an edge when I speak, but I need moderate intensity. How do I get there? I took five minutes to center before I went on air.

I started the interview in a better emotional state. During the interview, I continued to monitor my emotions. When I felt my emotions ramping up too much, I took a deep breath (after covering my mike). I touched my signet ring to remind me of my purpose and passion. Listening to the recording of the interview, I observed good content, good grammar and clear phrasing but too many fillers (ums and ahs). I was probably still too much on edge. I will do better next time. Interview performance, like emotions, can be mastered.

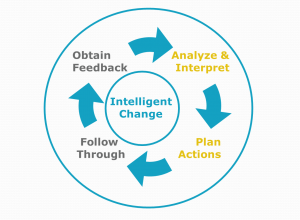

At Slade & Associates, we create dialogue and insight for intelligent change. Intelligent change often means exceeding preset boundaries. There is no upper limit on your emotional competence. You can learn to manage emotions. Like managing projects, going to college or radio interviews, you just need to work at it.

Interview: Managing Emotions and Coaching

Allen Slade with Elaine B. Grieves

This one hour conversation covered how to manage emotions and the positive impact of coaching. The interview appeared on Leader Talk, an internet radio show.

Feedback Should be “Just Right”

Allen Slade

A careful reading of Goldilocks and the Three Bears suggests three lessons for leaders: Moderation in all things. Don’t be impulsive. Breaking & entering causes problems, especially at the Bears.

Previous posts have looked at The Problem with Feedback and Different Perspectives on Feedback. Today, we will consider moderation in two aspects of feedback. Instead of a single feedback cycle that may be too hot or too cold, just right feedback requires that you mix the timing of your feedback cycles. And, don’t just impulsively act on feedback. Use insight and analysis to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose.

Multiple Feedback Cycles

As a leader, you should be open to feedback because you need to know “When I walk in the room, who shows up for the other people?” You need to seek out feedback relentlessly.

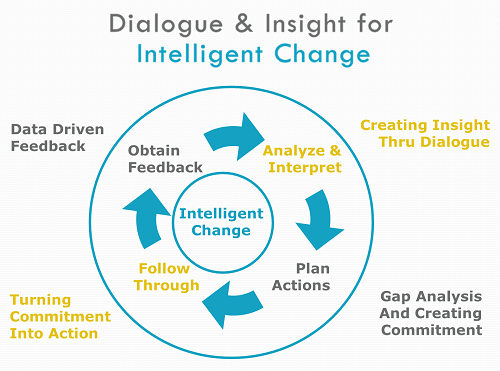

But it is not enough to collect feedback tidbits. To drive intelligent change, you must analyze and interpret the feedback you receive. You must plan actions based on the feedback. You must follow through with your plans. Then, you must start the cycle again by collecting more feedback. If things are going well, continue on. If your feedback suggest things are not going well, change something – your follow through, your action plan or your analysis and interpretation of the feedback. This feedback cycle drives intelligent change.

How long should your cycle take? Consider feedback cycles of three lengths:

Long-cycle feedback. This is feedback on long term impact, such as data from the annual employee opinion survey or a 360 report. Long-cycle feedback looks at the sum of your actions over a period of time. Long-cycle feedback is typically generated by the organization with safeguards to increase its validity (e.g., anonymity) and relevance to organizational leadership (e.g., a competency model). Yet long-cycle feedback by itself is not enough to develop your leadership. The assessments underlying long cycle feedback are complex and open to rating errors. And, a leader cannot afford to wait a year to find out if leadership changes are effective.

Short-cycle feedback. This is feedback on a recent event, such as post action feedback right after a meeting. Short-cycle feedback looks at your actions in the very recent past. The advantage of short-cycle feedback is that it reduces the delay in adjusting a new behavior. The disadvantages of short-cycle feedback are often a lack of anonymity and a lack of structure.

The quick check-in is a useful form of short-cycle feedback. After a conversation or meeting, ask “How did today’s conversation (or meeting) go for you?” Most of the time, the answer will be “It went well.“ or ”Great.” In that case, continue on. Sometimes, you will hear something of incredible value. “We are bogging down in the data.” “To be honest, I was bored.” “You have spinach between your teeth.” Treat this feedback as a valuable nugget. Adjust the agenda, amp up the excitement or do a quick floss job.

Instant feedback. This is feedback in the moment, such as watching non-verbal language of others in a meeting or hearing a change in voice tone during a phone call. Instant feedback allows the leader to adjust on the fly. Instant feedback requires mindfulness of the cues that others give in the moment. It also requires the ability to multi-task by talking and watching, by focusing on your message and your impact on the other party, at the same time.

You need a mixture of these cycles. Instant feedback and short-cycle feedback, in excess, may be too hot. Long-cycle feedback, by itself may be too cold. But, combined in the right proportions, these different cycles can be just right.

Balancing Openness to Feedback with Constancy of Purpose

When you receive feedback, another form of moderation is needed. You need to consider the feedback before acting. In the heat of the moment, while receiving negative feedback, you can go overboard. You can impulsively agree to do everything the feedback giver wants. This strong desire to please can backfire. If you submit totally to the other person’s judgment, you undermine the powerful dialogue that should come with feedback. And, you subordinate your purpose to their goals for you. In effect, you jump from feedback to action plan without your own careful analysis and interpretation.

It is better to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose. The other person’s feedback is always valid and always valuable. Yet their goals for you may not be identical to your purpose. My advice is to accept all feedback from all willing parties, without necessarily submitting to their action plans for you. The balanced reaction to feedback is to listen, to learn and to engage the other person in mutual problem solving.

Back at the Bears

Let me close with another observation: Goldilocks had no support team for her decisions. Impulse can be moderated by wise counsel. Mixing feedback cycles is more complex than simply waiting for annual leadership feedback. Balancing openness to feedback with constancy of purpose is harder than a simple rule for action. I recommend using the power of collaboration to maximize the power of feedback. Work with your circle of trusted advisors, your mentor or your leadership coach to master feedback. Gather a support team to create dialogue and insight to drive intelligent change for your leadership.

Bottom line: As a leader, actively seek feedback. Gather the right mix of long-cycle, short-cycle and instant feedback. Balance constancy of purpose with openness to feedback. Gather your support team to get your use of feedback just right.

And don’t break & enter, especially at the Bears.

The Problem with Feedback

Allen Slade

Most of us readily accept praise. But leaders can struggle with accepting and acting on constructive criticism. They can balk at negative feedback. Sometimes, it is reasonable to reject feedback because of its low credibility or irrelevance. However, habitually rejecting feedback suggests a deeper pattern – a world view that sees feedback as a problem.

Let’s get personal. How you respond to negative feedback?

Recall the last time you got substantial negative feedback on your work performance or professional relationships from your manager, colleague or close friend at work. How did you react?

1. I saw the feedback as an attack or threat.

2. I saw the feedback as disapproval or judgment.

3. I defended myself, denied the feedback was valid, or delayed receiving the feedback.

4. I accepted the feedback, even though I wanted to do well.

5. I welcomed the feedback.

6. I invited additional feedback.

Suzanne Cook-Greuter lists seven ways to respond to feedback[1]:

Opportunist. Focuses on own immediate needs and opportunities. Values self-protection. Receives feedback as an attack or threat.

Diplomat. Focuses on socially expected behavior. Values approval of others. Sees feedback as disapproval or judgment.

Expert. Focuses on expertise, procedure and efficiency. Values expertise in self and others, but takes feedback personally as an attack on own expertise. Defends, denies, and delays feedback, especially from lesser experts.

Achiever. Focuses on delivery of results. Values effectiveness, goals and success. Accepts feedback if it helps achieve personal goals and improve effectiveness.

Individualist. Focuses on self interacting with the system. Individual purpose and passion are more important than the system. Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of their own behavior.

Strategist. Focuses on linking theory and practice. Looks for dynamic systems and complex interactions. Invites feedback for self-actualization.

Magician. Focuses on interplay of awareness, thought, action and effects. Values transforming self and others. Views feedback as natural and essential for learning and change.

Today’s post focuses on opportunists, diplomats and experts – those who have response 1, 2 or 3 to negative feedback. Let’s look at each in more detail:

1. An opportunist lives for the moment, seeking passion with little long-term purpose. Since feedback is painful, the opportunist sees it as an attack or threat.

2. The diplomat wants to get along well with others. Feedback is disruptive. The diplomat prefers smoothing over differences.

3. Experts do not like feedback in their area of expertise, because it undermines their expertise. An expert will grudgingly accept feedback from a superior expert, but they often defend themselves by attacking the other person’s expertise.

Because of their problem with feedback, opportunists, diplomats and experts often struggle as leaders. In my experience, leaders must see themselves through the eyes of those they wish to lead. Cook-Greuter found that over 50% of adults have the mindset of an opportunist, diplomat or expert[2]. If half of us struggle in accepting feedback, is it any wonder that there is a shortage of effective leadership?

Bottom line: If you have a problem with feedback, you will struggle as a leader. Shift from seeing feedback as a problem to seeing feedback as a gift.

I am optimistic that anyone with a passion for leadership can develop the purpose necessary to accept feedback. Anyone who wants to help people can develop the norm that feedback is acceptable. Anyone who wants to be the best leader possible can become an expert in seeking and using feedback.

Changing your view of feedback is not easy. It requires substantial growth and development, possibly even a fundamental shift in your world view. Reflection, coaching and practice may help you open yourself to negative feedback. Reflection, such as a journaling, meditation or quiet time, can help you examine yourself and shape your impact as a leader. Leadership coaching helps you create a plan to improve your feedback skills and hold yourself accountable to put that plan in action. Like any other competence, practice accepting feedback is necessary. You need to find the right situations to practice receiving negative feedback. You may want to start in a safe and supportive environment, such as with your coach or in a training class. Then, practice with your trusted circle of advisors in your work situation. Soon, you will want to practice requesting feedback from a wider circle – including people whose expertise or motives are not always clear. Feedback from the bozos and politicians is a gift, because their perspective impacts your leadership as much or more than your circle of trusted advisors.

The problem with feedback is our unwillingness to receive negative feedback. The solution is simple but difficult: See feedback as a gift. If you solve the problem with feedback, if you tackle this simple but difficult change, you will become a better leader and lead a richer life.

[1] This table is adapted from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004) “Making the case for a developmental perspective,” Industrial and Commercial Training, 36, 275-281.

[2] Data from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004), p. 279.

The Tipping Point of Performance

Allen Slade

I love sports movies, especially about underdogs. The critical moment is when the coach or loved one gets the underdog fired up. I love Rocky II, when Talia Shire lights Rocky’s fuse from her hospital bed and Remember the Titans, when Denzel Washington gives a moving call for unity in the Gettysburg cemetery.

As a leader, do you try to fire up your team? Be careful. If you play with fire, you can get burned.

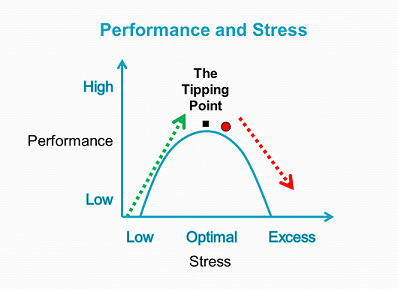

Clearly, there are times when you need to establish a sense of urgency. But asking for extraordinary effort can backfire. As the performance curve below shows, there is an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between stress and performance does hold, but only in the green zone.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

The problem hits at the top of the curve. When a person reaches the tipping point, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance leads to a downward spiral in the red zone. People become anxious. They act indecisively, work slower or make more mistakes. As their performance decreases, their anxiety increases, further decreasing their performance. Notice the red marble at the top of the performance curve. In the red zone, the marble accelerates down the curve of poor performance. As a leader, if you push a person too far, their performance drops. And, their performance will continue to get worse because of the downward spiral.

Bottom line: Push for performance, but avoid the tipping point for stress. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Aim for high performance, not peak performance. I coach leaders to avoid pushing people to their tipping point. If the tipping point is at 100% performance, aim for 90 or 95%. Then, your team member has a stress buffer. If there is a coffee spill that wipes critical data or a car wreck going to the big meeting, they will have the psychological reserves to get through it. If you push to get the full 100%, your people may tip into the red zone.

Develop your people. If you wish to increase performance, but a person is near the tipping point, think development first, motivation later. Increase their competence and capacity, so they can perform better while maintaining an essential stress buffer.

Be a lifeguard. Your people can drown in stress. The downward spiral of performance undermines decision making and behavioral flexibility. If someone is in the red zone, you may need be their lifeguard. Watch for signs of stress in your team members, watching for people at the tipping point or in the red zone. Then, throw them a life line. Offer more resources, renegotiate deadlines, offer them time off to refresh and rest. Be creative – think of the rousing speech that fires up the underdog, then do the opposite.

Know your team. Everyone is different. The people you lead have different capabilities and stress tolerances. They will show different warning signs of a stress-induced performance crisis. Get to know your people before a crisis. Have regular dialogue with every team member. Seek insight about their performance patterns, personal stressors and individual signs of overload. This will equip you to be a stress lifeguard.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

Smart Goals

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders set goals for themselves and others. The most powerful goals tend to be specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Here are my thoughts on how to set smart goals:

Specific – the goal states a specific outcome or action. If your goals are stated only as outcomes, there may be no obvious steps to take. You don’t want to be like the basketball coach who talks about winning but has no plan for today’s practice. If all of your goals are actions, you can get disconnected from your ultimate purpose, like the basketball coach who focuses only on holding a great practice. I encourage my clients to set a mix of outcome goals and action goals, covering both the end to be achieved and the means to that end.

Measurable – the goal can be assessed against an objective standard. We tend to value what we measure and measure what we value. Without measures, your goal is light-weight. The measures can be hard, in the form of objective numbers. Numeric metrics are straightforward, but easy to measure does not equal important. Your measures may need to be soft, in the form of assessments of key stakeholders. And some measures are binary: Did the desired activity or outcome happen (yes or no)? Different goals require different metrics, but all goals should be measurable.

Actionable – the goal can be acted on by the person who holds the goal. Your goals are powerful only if you can personally take steps to accomplish the goal. As a leader, set goals with your team that are in their realm of possiblity. Otherwise, you will undermine their motivation and your credibility.

Realistic – the goal is difficult but attainable. Harder goals increase performance. But goal difficulty has limits. When a goal becomes unrealistic, its power disappears. When setting goals for ourselves, you should think through your odds of success. When setting goals with others, have an open two-way discussion of the goal to get the level of difficulty right. Difficult goals are good, but they must be attainable.

Timebound – the goal has clear timing, either a date or a rate. For one-time goals, use a due date. “I will accomplish this action by April 1 of next year.” For ongoing goals, use a rate of action or outcome. “I will sell $100,000 of new consulting business per month.” Without a date or rate, a goal is not specific or difficult.

With all five smart features, your goals will have maximum impact. And, all five feature should reinforce each other. The specific actions should be realistic, the metrics should have a date or rate, etc.

It is possible to go overboard – to be too smart for your own good. With my leadership coaching clients, less is usually more. At first, I encourage them to focus on just one or two behaviors to change. Taking on too many changes creates frustration rather than change. We often start with goals that are general. For example, a client increasing visibility might start with “Notice how much airtime I take up in meetings.” This is not specific, but sometimes that is all that is needed to trigger change. If a stronger trigger is needed, we move to a more specific goal, such as “I will speak up twice in every meeting.” If that doesn’t works, we can move to an even smarter goal, such as “In Monday’s meeting, I will comment twice on product quality. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story.”

Almost every goal could benefit from being a bit smarter. Yet consider what works for you. Some people thrive on smart goals tightly linked to their life purpose and their daily schedule. Others need nothing more than a Post-it reminder. And, once your goal is in play, notice how it works for you. If you are making progress and accomplishing what you want, that goal is right for you. If your goal is not working, consider making your goal smarter.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

It is also important to agree on metrics and time for each goal at the beginning. Then, during the peformance review, you and your team member will be on the same page with feedback.

Bottom line: You should set specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound goals, for yourself and for others. When setting goals with others, have lots of dialogue. Be smart – create dialogue, insight and powerful goals to drive performance.