When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Balancing Airtime in Your Meetings

Allen Slade

Some people think meetings are just a waste of time. At one level, meetings exist to share information and to make decisions. (It doesn’t always work, but that’s the plan.) At another level, leaders should see meetings as leadership development opportunities. Jim Clawson says effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a meeting, energy shows up most clearly as spoken comments. One way to think about managing the energy in meetings is airtime.

Airtime is the percent of time you are the focus of the team’s attention (talking, writing on the board, etc.). For a five person team with equal attention, each person should be the focus of attention about a fifth of the time – 20% airtime. A person dominating the conversation has 50% or more airtime.

It is rare that each person gets exactly the same airtime in a meeting. You may have more airtime because your expertise or passion fits the topic.

Once you get a handle on your own airtime in meetings, notice the airtime of the people around you. Some people may dominate the meeting (take up most of the airtime) while other people almost never speak. In some meetings, unbalanced airtime makes sense. The high airtime person may have unique information or expertise that will help move the meeting ahead.

All too often, though, unbalanced airtime comes from ineffective meeting dynamics. There may be personality differences that drive airtime, such as extroverts speaking endlessly and introverts staying quiet. There may be cultural norms that prevent some from speaking up, such as power distance or gender roles. There may be managers who love to hear their own voice. There may be politics at work, with the deliberate attempt to keep certain ideas or people out of the discussion.

If you want to balance out airtime, here are some tactics:

Draw in the silent majority. Ask a quiet person a direct question. Often, when you break the ice, they will find it easier to participate in the future.

Gently redirect dominators. If someone takes up too much aritime, use an appropriately assertive statement such as “Let’s hear from some other people now.”

Restructure the conversation. Try beginning the meeting with an icebreaker exercise or by asking everyone to briefly report on activities or results. During the meeting, ask everyone to comment on the issue or decision.

Get a facilitator. If the meeting continues to be ineffective, look to bring in a facilitator. The facilitator can help you redesign the meeting beforehand. He or she can also help with in-the-moment interventions to get the meeting rebalanced.

When managing airtime in your meetings, you are not striving for perfect balance. Instead, you are looking to get everyone engaged in the meeting. Balanced airtime will make meetings more interesting. It will help your information sharing and decision making more effective. Balanced airtime will maximize leadership development of others. And, actively managing airtime for yourself and others will become another tool in your leadership toolbox.

Holding a Difficult Conversation

Allen Slade

You are gearing up for that difficult conversation. It may be about a broken commitment, setting a boundary to halt abusive behavior or feedback that is unexpected and unwanted. You want to navigate the emotional minefield to minimize the chance of a catastrophic explosion.

Now what? How do you plan the difficult conversation for maximum gain and minimum risk?

Start with the end. In a previous post, I recommended planning your difficult conversation by starting with the end. Have a clear definition of success. Be sure the potential reward of the difficult conversation is worth the cost.

Don’t procrastinate. Bad news is like bread. It is best fresh. After a few weeks you don’t want it in the house. If you need to have a difficult conversation, do it sooner rather than later. If you need time to think and plan or if you want to check your plan with a coach or mentor, fine. But think of waiting hours or days, not weeks or months.

Begin well. Plan your opening statement. Make it appropriately assertive, following this pattern: When you [specific behavior, attitude or thinking pattern], it makes me [specific negative outcome.] Here are some examples:

“When you roll your eyes while we talk, I feel disrespected.”

“When we discuss customer complaints, you tend to blame other employees. This makes me think you don’t see a need for change.”

Listen more and talk less. Be curious about the other person’s reaction. Look to discover why they act/feel/think like they do. Don’t argue. Don’t project an attitude of certainty. Practice active listening by reflecting back what they say and asking lots of clarifying questions.

Anticipate their reaction. At a basic level, put yourself in their shoes. If you were on the receiving end of this difficult conversation how would you react? Even better, figure out the other person’s general pattern of responding to feedback. Do they have a problem with feedback or are they generally open to feedback? Then, prepare for their reaction. Control your emotions, listen without agreeing and keep the conversation moving ahead to address the issues.

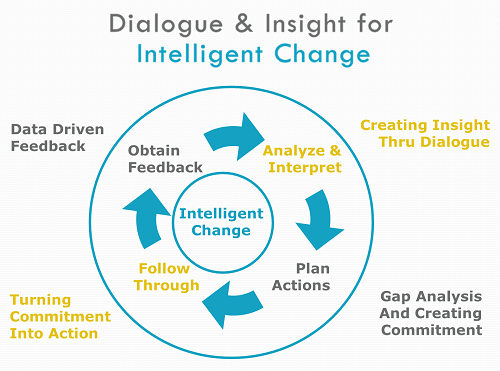

Seek mutual problem solving and commitment. The goal of a difficult conversation should be intelligent change. To change, you need to work with the other person, first to figure out how to change and then to get a commitment to change. You should aim for a smart request, a specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound proposal that the other person accepts.

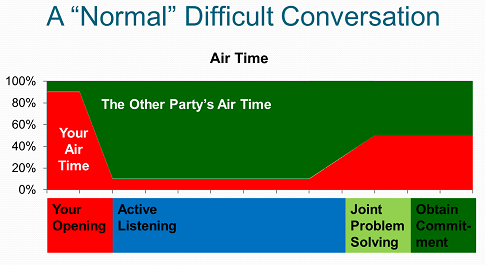

When you are at your best as a leader, your difficult conversation should follow this pattern.

You will give most of the airtime to the other person. Only during your brief opening will you do most of the talking. The longest part of the conversation is your active listening, where you may do 10% of the talking or less. When you get to joint problem solving and mutual commitment, you should look to do 50% or less of the talking.

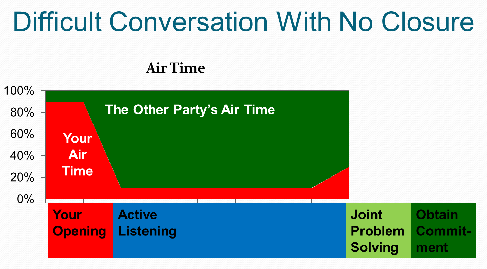

Let’s be realistic. Some difficult conversations do not end with a solution. The other person may be too stubborn. If you do your part well, but the other person resists your efforts, your difficult conversation may turn out like this.  This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

I had a difficult conversation with an intern that started: “Dolly, your work has been slipping recently. Several people have reported smelling alcohol on your breath. I am concerned about your reputation. I am reluctant to assign you to important projects or have you go to meetings without me.” Dolly never admitted to a drinking problem. She did not agree to seek help. Yet, the issue disappeared overnight. When her internship ended months later, I gave her high performance ratings and a stellar recommendation.

If the other person has difficulty admitting a personal failing, there can still be change, but it will follow a different pattern. The individual you confront may go back to their office and think about what you said. Sometimes, that triggers the change you seek. They may never admit you were right or confess their shortcoming. That’s OK. You can live with the change even if you don’t get the apology.

The worst case is that change does not happen. Let’s acknowledge that we are dealing with adults. You can’t make the other person bend to your will. Give it your best shot – hold the most effective difficult conversation you can – but accept that they must decide whether to address your concerns. If they do not change, you can make other moves. You can set boundaries, end the relationship or get others involved in resolving the situation. Your key responsibility is to have the best difficult conversation you can without pretending you can control the other person’s reaction.

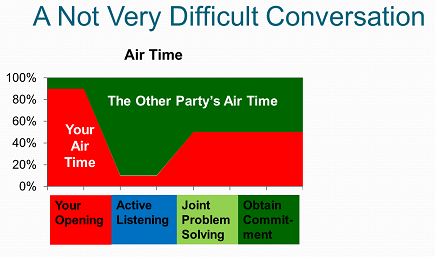

I have coached many clients on how to hold a difficult conversation. We work together to craft a powerful opening. We practice listening. We practice managing emotions. We even role play the difficult conversation. And then, my client goes off to hold the conversation. Surprisingly often, my client is surprised because the conversation turns out to be not very difficult at all.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

My thanks to executive coach Art Gingold for refining my thinking on difficult conversations.

Planning a Difficult Conversation? Start with the End

Allen Slade

You need to have a difficult conversation.

You know the conversation I mean. The conversation you keep putting off. You get butterflies just thinking about it. You know it will not be pleasant.

Your difficult conversation may be confronting someone about broken promises. It may be setting a boundary with someone who tramples over you or other people. You may be planning to share feedback that is unexpected and unwanted. Whatever the topic and whoever the other party, your difficult conversation feels like stepping into an emotional minefield.

As a leadership coach, I help clients hold the difficult conversation they have been putting off. To increase the odds of success, we work on two things: planning the conversation backwards and designing the conversation for maximum impact. Today, let’s think about how to plan your difficult conversation backwards. In other words, the best difficult conversations start with the end.

In planning a difficult conversation, always plan backward. Define a successful outcome for the difficult conversation before you hold it.

In planning a difficult conversation, always plan backward. Define a successful outcome for the difficult conversation before you hold it.

What does success look like? What change would you like to see in the other person? It might be a change in behavior, such as an employee returning phone calls promptly. It might be a more subtle change in thinking, values, attitudes, beliefs or expectations. Sometimes your desired change is not in the cards – the other person does not share your motivation, your definition of success or your norms. Sometimes, the endgame is just not feasible.

Is it worth it? How much risk will you take? Some difficult conversations put your relationship at risk. While things may improve, you can also harm the relationship by opening emotional wounds. A difficult conversation can also harm your credibility with your wider circle of influence. You must decide if the probable pain is worth the potential gain.

Starting with the end will show you a lot of difficult conversations should not happen:

Don’t tilt at wind mills. Risking much with little odds of success is not a good bet. Don’t confront your boss during your performance review meeting, especially if you expect poor ratings. Don’t ask the CEO snide questions during the strategy rollout. Don’t voice complaints about the company on your last day of work. If you don’t have the standing to make a positive change, save your energy and your reputation.

Don’t do it to let off steam. Don’t hold a difficult conversation because you “have” to tell them something. If you are holding a difficult conversation to vent your frustration, punish the other person or get something off your chest, just don’t. Unless you can visualize a successful change in the other person, don’t start a difficult conversation. Talk to your therapist, write in your journal or yell in your private closet instead.

Don’t call out strangers. Grocery store parenting advice, barroom etiquette instruction and roadway driver’s ed rarely stick. Worse, strangers can react strangely with nasty expressions, verbal abuse or violence. Little upside and potentially grave downside make difficult conversations with strangers a bad bet.

By avoiding fruitless difficult conversations, you will be happier and healthier. You will also have more energy for the conversations that have the right end game. Then, with the proper planning, you can improve a relationship, change someone’s ineffective behavior or chart a new direction. You can have difficult conversations with the outcomes you seek, if you start with the end.

A Declaration for the Center

Allen Slade

Before my first meeting with Bill Gates, I had every reason to be confident. Microsoft had recently recruited me for my specialized expertise. I had conducted similar meetings with other CEOs. I had a good team behind me, and I had practiced the presentation thoroughly.

The first five minutes went well. Then, Bill asked a question on a minor point. I gave a simple answer, but Bill kept drilling down on the topic. On Bill’s third or fourth question, my confidence evaporated. I was in a full scale amygdala hijack. I needed to quickly reestablish my confidence or the meeting would be a failure.

In Getting to the Center of an Emotional Storm, I suggest centering in the moment as a tool for managing your emotions as a leader. When you are in the spotlight, and your emotions are not serving you well, you can breathe, use a touchstone or make a silent declaration. While declarations can be overplayed by motivational speakers or by comedians (“I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.”), the right declaration can help you manage your emotions. I help my clients find declarations that work, and if declarations don’t work, we focus on other tools for managing emotions.

Declarations help direct our actions. Chalmers Brothers points out how declarations help steer things in the right direction:

For organizations and for individuals, declarations can operate like the rudder of a boat. The boat (organization or person) changes directions as a result of those with authority declaring one thing or another. Declarations are how we identify our priorities and commitments to the future and how we bring certain ways of being into existence (self-worth, well-being, dignity, among others).

For the purposes of managing your own emotions, a compelling personal declaration points you toward a different future. For someone with a fear of public speaking, an effective personal declaration might be: “I will speak with confidence.” This declaration would help moderate anxiety before and during a speech.

The “right” declaration hinges on your personal emotional life and the situation you face. Over the years, my clients have come up with a variety of compelling personal declarations: Stick the landing. Rest my hands. Be confident. Manage my emotions. Re-center. Pause for power. Speak slowly. Build credibility. Make the sale.

Four things will help make a declaration effective in managing your emotions:

Make it simple. Use short, declarative statements.

Make it positive. Don’t use “Don’t . . .” because the stickiness of the last word. “Don’t fidget” focuses the attention on fidgeting, and that will echo in your mind. Stay positive. “Be confident” or “Stick the landing” focuses attention on the new future you are declaring.

Make it powerful. Your declaration must resonate. It must make sense (impacting decision making in your prefrontal cortex) and it must also have emotional weight (impacting emotions in your amygdala).

Make it memorable. Your declaration has to be on the tip of your tongue. Stating your declaration so it is simple, positive and powerful helps. You also need to practice your declaration, starting in safe settings such as your office or with your coach.

So, how did my meeting with Bill Gates turn out? During my amygdala hijack, when my confidence was at its lowest, I centered in the moment. I took a breath, touched my signet ring and said to myself “I am one of the three best people in the world on this topic. You hired me to fix your problems.” I smiled quietly, and re-engaged with confidence.

Many Mini-Experiments

Allen Slade

In Teachers, Mentors and Coaches, I made the case for the value of coaching for adults who want to grow as leaders. Teachers impart expertise. Mentors impart experience. Coaches create dialogue and insight for intelligent change. And a big part of what coaches do is to create mini-experiments.

Coaching dialogue is different from normal conversation. At the beginning, a client and I reconnect and check on previous mini-experiments. In the middle, we discuss the issues facing the client. I bring active listening, powerful questions and direct communication to the conversation. I do not bring an agenda. You, the client, set the agenda, because you are the expert in your own situation. If you want to talk about next week’s meeting, the marketing strategy, a difficult customer or the new IT system, I am good with that.

If the first 50 minutes are dialogue and insight, the last ten minutes are action planning. I work with my clients to create mini-experiments at the end of each coaching session. A mini-experiment is an action plan to try something new and different. For an executive, this might be a different approach to growth strategies. For a leader, it might be managing emotions before a speech. For a career coaching client, it could be a simulated interview. Since the client is the expert on the situation, I propose mini-experiments as a SMART request. The mini-experiment is SMART because it is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. It is a request because the client can respond yes, no, offer to negotiate or decide later. We usually negotiate – the client raises valid concerns, and I ask “What would work?” Together, we create something SMART that can drive intelligent change.

Whether in the physics lab or the conference room, an experiment requires a hypothesis and measures. The hypothesis might be “If I do [something different], then my strategies/speech/interview will be better.” To figure out whether the hypothesis holds water, we need measures that produce data. The best data will compare the old way of doing things with the new way. This data needs to be credible and relevant to you the client, so that you are confident of your evaluation of the different way of doing things. We probably don’t need the rigor of a sophisticated experimental design or statistics. What works for you works for me as your coach.

A leadership coaching client was having difficulty with a key executive. Our coaching conversation hinged on how the executive fell short of expectations. However, my client saw the needs of his customers as an opportunity for creative problem solving and servant leadership. We reached a key insight: customer shortcomings were energizing but executive shortcomings were deflating. We designed a mini-experiment: “Think of your boss as your customer for the next week. See how that impacts your attitude toward your boss.” At our next coaching session, I checked on how the mini-experiment went. My client reported it was hard to think of his boss as a customer. But when he did, he had a more positive attitude, resulting in upward problem solving and service to his boss.

This was not a “bet your career” experiment. It happened to work. If it had not worked, we would have discussed why, and either tried the “boss as customer” idea again with a SMARTer action plan or else come up with a new approach. Because of minimal risk, quick turnaround and limited effort, you can do many mini-experiments.

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

Negotiation: The Dance of Requests and Offers

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Requests and offers make up the dance of negotiation. An offer is the mirror image of a request. With a request, you are triggering action by the other person. With an offer, you are proposing to act for the other person. An offer requires a valid response, just like a request: Yes, No, Counter Offer or Decide Later. It is the back and forth of requests paired with offers and offers followed by counter offers that creates the dance of negotation.

A succesful negotiation leads to an agreement that meets the interests of both you and the other person. Bill Ury distinguishes several forms of negotiation:

Hard positional bargaining. “Participants are adversaries. The goal is victory. Demand concessions as a condition of the relationship. Distrust others. Dig in to your position. Make threats.”

Soft positional bargaining. “Participants are friends. The goal is agreement. Make concessions to cultivate the relationship. Trust others. Change your position easily. Make offers.”

Positional bargaining, hard or soft, locks in positions and makes the negotation a win-lose game. Positional bargaining tends to produce unwise agreements, inefficiency in the bargaining process and stress in an ongoing relationship. I have purchased a number of cars using hard positional bargaining. Even if we reach an agreement, the bargaining is adversarial, long and dissatisfying, at least for me as a customer.

Principled negotiation is when the parties go beyond positions to the underlying interests and look for win-win solutions. Four steps will help you do this:

- People: Separate the people from the problem.

- Interests: Focus on interests, not positions.

- Options: Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do.

- Criteria: Insist that the results be based on some objective standard.

I use principled bargaining to buy and sell cars. For my last car purchase, I looked for a dealer who would agree to principled negotiation. Over the phone, we agreed to use a price that was $250 over dealer cost. The face-to-face negotiation was amicable, efficient and mutually satisfactory.

Is principled negotiation better to hard or soft bargaining? It depends. I keep all three forms of bargaining in my leadership tool box. I tend to use principled negotiation in ongoing relationships dealing with a substantive issue. Negotiating on principles builds relationships while building agreements. I may use hard positional bargaining when there is no long term relationship and the other person is treating the situation as a win-lose game. I may use soft positional bargaining when the relationship is key, the other person is passionate about their position and I am flexible on the issue.

If you practice the steps of requests and offers, you will be able to dance to a variety of music. Make smart requests. Make big asks. Give and demand valid responses. You can adjust your negotiation style to the heavy metal of hard positional bargaining, the swing dancing of soft positional bargaining or the long term romantic dance of positional bargaining. If you influence the play list, you may be able to set the style of negotiation you prefer. Otherwise, negotiate to the music being played.

Making Unreasonable Requests: The Big Ask

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Usually, I recommend SMART requests: requests that are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. But should a leader’s requests always be realistic? According to Kim Krisco, a leader accelerates change with unreasonable requests:

The primary speech act that creates action and increases velocity is the request. The more requests, the more action and change. The more unreasonable the requests, the greater the change. Indeed, you might say that the function of a leader is to make unreasonable requests.

An unreasonable request is a big ask. When should leaders make the big ask?

Bottom line: I believe you should use the big ask rarely, and well.

A big ask is a stretch for the other party. Make sure you have the creditability to make it stick. If you make the big ask too often, you will undermine your credibility as a leader and your future requests will have less impact. You must prove that signing up for your big ask is a good idea – your request will pay off for the organization and for the other person. A big ask, if accepted by the other party and mutually beneficial when fulfilled, can add to your creditability. If the check is accepted, and it cashes, you get another blank check.

You must be especially well prepared for the big ask. The big ask should be given only when you are at a peak level of leadership presence – passion and purpose, emotions, body, relationships all need to be in congruence with the big ask.

The big ask is a declaration which can create a bold, new future. In 1961, John Kennedy declared “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” Most requests should be realistic. But realistic requests would not have gotten Neil Armstrong to the moon in 1969. The big ask should be used rarely, and well.

Leaders should be able to make the big ask. They should also encourage risk taking by supporting the big asks of others. Soon after I started at IBM, my manager said to me “Allen, you get one blank check. If I don’t agree and you insist, I will back you. But only once. If that check cashes, I will give you another blank check.” In effect, he advanced decision making credibility to me, despite my lack of experience. He encouraged me to make the big ask, but to make it rarely and well.

Do you insist that people prove their credibility before you will take a risk on their decision making? Try advancing some decision credit instead. It can be scary to give up control, so you can start with just one blank check. See what happens when you back someone’s big ask. The spark of initiative that results may flame into a bonfire of innovation.

Response Required

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders use requests to trigger action. If your requests don’t trigger the action you want, you may need to make smart requests. But even the most carefully crafted request requires discipline in listening for the response.

Bottom line: For all your requests, insist on one of these responses:

1. Yes

2. No

3. Counter offer

4. Decide later

As Kim Krisco says, “If you let someone give you anything except one of those responses, there is a good chance that the action you want and need will not be forthcoming.“ A non-response, changing the topic or refusing to answer are not valid responses. As a leader, insist on “yes”, “no”, an offer to negotiate or a commitment to decide later. Demand a valid response out of self-respect and out of respect for the other person, because a request requires a valid response.

If you will not accept “no” as a response, what you are saying may be a command or a demand, but it is not a request. Requests may be stated politely while commands and demands often use more forceful language. However, commands may also be phrased quite politely. For a Navy ensign, the statement “The captain requests the pleasure of your presence on the bridge” is clearly a command, because the captain has substantial legitimate power over the ensign. The polite phrasing may be an attempt to soften the command, or it may actually reinforce the power differential. Either way, the ensign will rush to the bridge.

Like a command, a demand does not leave room for “no”. If a command is based on formal authority, a demand is based on coercion. A demand has an edge to it. “Do what I want or else . . . .” The “or else . . .” may be stated boldly in the form of a threat. Or it may be implied with language such as “I have the right to . . . .” Insisting on your rights implies that you can call for backup to enforce your rights, such the police or Human Resources. Either way, a demand lays out the choice of acquiesence or escalation.

This is not to say that a request, once made and rejected, is forever dead. An influential leader may test a negative response. After hearing “No,” the leader can ask “Why not?” or make a counter offer. Yet, a leader will allow the recipient to refuse a request. Being willing to accept “No” as a valid answer is fundamental to your respect and authenticity as a leader.

As leaders, we draw on our interpersonal influence, not formal authority, coercion or rights. We use requests to trigger action, not commands or demands. We may find ourselves in other roles – as a manager with legitimate authority or an employee with rights – and in those roles we may choose to use commands or demands. But if you are acting as a leader, use requests to trigger action. Insist on hearing “yes”, “no”, an offer to negotiate or a commitment to decide later. You may not always get what you want, but you increase the odds when you insist on a valid response to your requests.

Making Smart Requests

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders use requests to trigger action. As Chalmers Brothers says:

We make requests when we have an assessment that the future is going to unfold in a certain way, and we don’t like that. We want the future to unfold in a different way than it seems to be heading by itself, and in order to put things in action to bring this about, we make a request.

Effective requests require discipline by the leader in how the request is made and what answers the leader will accept. In another post, we will think about what answers a leader should accept for a request. But today, let’s look at how to phrase your requests for more influence.

Here’s the bottom line: If your requests don’t trigger the action you want, try making your requests SMART – specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time bound.

Specific – the request states a specific behavior or outcome to be achieved. To get more action, our request for better responsiveness could be phrased as “I would like all customer voice mails to be answered promptly.” This request defines the desired behavior more specifically.

Measurable – As with smart goals, we value what we measure and measure what we value. A request that cannot be measured will have less impact.

Actionable – the request can be acted on by the person who receives the request.

Realistic – the request can be actually met. An actionable and realistic request is something the other party can reasonably commit to fulfilling.

Time-bound – the request should have clear timing, usually either in the form of a rate of accomplishment or a deadline. A rate of accomplishment might be “I would like to have you contact 10 customers a week for feedback.” A deadline might be “I would like each person in the support team to answer all their voice mails by the end of the day they are received.”

Be specific about who will achieve the outcome. “I would like us to answer all customer e-mails promptly” implies that the you will do some or all of the answering. “I would like you to answer all customer emails promptly” makes the responsibility more specific. The difference between “us” and “you” is an example of diffusion of responsibility. In making a request, be specific about who will act. Diffusion of responsibility increases with group size , so the leader making a request to a group needs to be even more clear in targeting the request.

Make all of your requests actionable and realistic. Unreasonable requests can undermine your credibility and alienate your audience. It does not matter how reasonable you think your request is – the key is whether the person receiving the request believes they can realistically take action to accomplish what you ask. Keep your ears and eyes open to see how your request lands with the other person. Adjust your request – timing or quantity – or negotiate additional resources to help the other person expect to be able to do what you ask.

Even a smart request can fail if you give the other person a ready excuse for ignoring your request. In general, a request has more power when it stands alone. A stand-alone request takes courage, especially in allowing the request to echo in silence. Leaders need to exercise courage, and often that means using a powerful request and waiting for the other party to respond.

How smart do your requests need to be? Smart enough to accomplish your purposes. If you make a vague request and it triggers the action you want, great! No need to tinker with success. On the other hand, if your requests are not working, try making them smarter. You may not always get the action you want, but you increase the odds with a smart request.

The Power of &

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Why Slade & Associates? Why not Allen Slade, LLC or some other name for this professional services firm? When I formed Slade & Associates in 1988, I knew my work. Whether I was training, writing, teaching or consulting, my best work happened with others. This is not a personality issue, since I am somewhat of an introvert. Instead, my work improves with the power of the team, the power of dialogue, the power of shared accountability. The power of &.

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” Our internal thinking can be a bit chaotic and illogical. When we share those thoughts with others, our thinking improves. The rules of language, the articulation of logic and the fear of looking foolish impose a discipline on our thinking that improves our ideas. Once we share our ideas, the power of dialogue kicks in. The people around us can sharpen our ideas with powerful questions, new information or with alternative ideas. The richness of the dialogue drives the quality of the insights.

For collaboration to work well, we need to work with people who we value and trust. We need to have people both challenge our thinking and support our work. At Slade & Associates, the people I choose to work with – my associates – make me better. They are confident, committed, and competent. They make me better. Together, we make our clients better.

The Slade & Associates mission is creating “Dialogue & Insight for Intelligent Change”. (Can you tell I like ampersands? This post could have been titled “The Power of & & &”.) We do not put on our expert armor when working with our clients. We don’t assume the consultant or coach has all the answers. Instead, my associates and I assume our clients are the experts in their own situation. We help move the dialogue along to create insight. We ask powerful questions. We bring in new concepts and new data. We light the match. Then, with our clients, we fan the flames to create insight to ignite intelligent change.

Do the people around you make you better? Does your thinking improve when you share it? If not, consider what is blocking the power of & for you.

You may not have the supportive environment you need for the power of &. Some work environments are too competitive for collaboration to really work. At Microsoft, many of my fellow directors had sharp elbows. The rewards for individual performance and the culture of the organization often overwhelmed the power of &.

If you are not experiencing the power of &, what can you do to increase collaboration? Three thoughts:

1. As a leader, you are responsible for maximizing the collaboration of your team. Get feedback on the level of collaboration on your team and figure out ways to increase collaboration. Do this with your team, not for them.

2. If your colleagues at work don’t trigger the power of & for you, consider creating a circle of trusted advisors for yourself. Find wise people with trustworthy motives and different perspectives. Open your thinking and plans to them. Dialogue with your circle of trusted advisors. Talk, listen and learn for your benefit and for theirs. Pay it forward by mentoring others.

3. Sometimes the fault lies within us. I can build healthy relationships through service, reciprocity and active listening. Or I can undermine my relationships with self-serving behaviors, a desire to take without giving and talking too much. To get the power of &, I need to do more than my part. If the people around me reciprocate by doing more than their part, we are on the way to powerful collaboration.

Create a collaborative environment with your team. Build a circle of trusted advisors. Reciprocate and listen. Go get the power of &, but don’t go alone.