When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

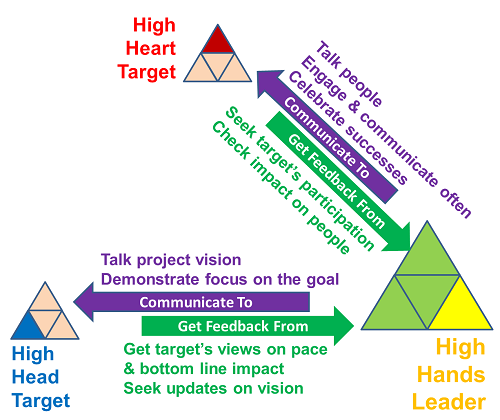

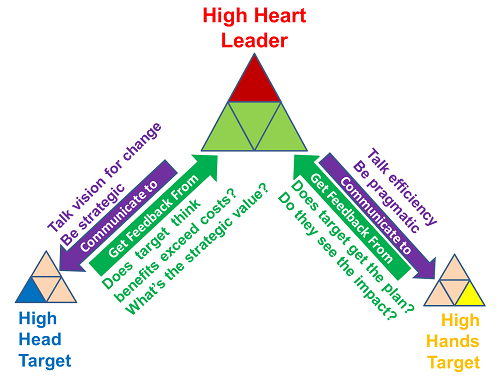

The Platinum Rule for People-Focused Change Leaders

Recently, we have looked at communicating change with the platinum rule for visionary change leaders and the platinum rule for “just do it” change leaders. Today’s post completes the set. We will look at how people-focused change leaders can effectively communicate in the midst of change.

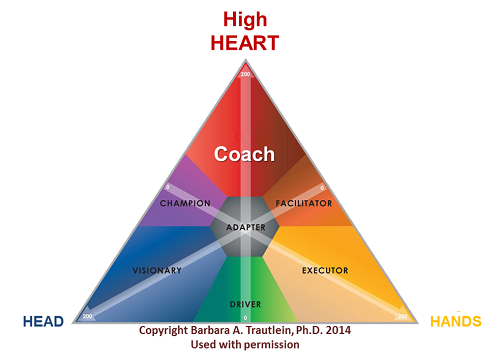

Heart-oriented leaders help engage and care for others in the midst of change. In Barbara Trautlein’s model of change intelligence (CQ), coaches, facilitators and champions are high heart change leaders.

But Enough About You. What About Them?

Self-awareness about your CQ style is important, but it is only the starting point. To be effective in leading change with a variety of people, you must know their CQ and how to best interact with them. Here’s a key principle:

People don’t think much about your CQ style. People want to be treated according to their CQ style.Trautlein refers to this as the platinum rule: don’t treat people like you want to be treated (the golden rule). Treat people like they want to be treated.

Let’s consider a front line supervisor who is a high heart change leader – a coach. The supervisor will naturally care for people in the midst of change. When the high heart leader deals hangs out with other high heart leaders, they will talk the same language and have the same people-oriented values. They will be a cardiac care unit.

However, when the supervisor gives a status report to a senior executive who is a visionary (high head change leader), the supervisor will fail if the meeting is only about people. The executive wants to know how the change details fit into the overall vision. The supervisor needs to talk like a visionary. And, the supervisor needs to get feedback from the executive on the strategic value of the project.

Suppose the high heart supervisor has a meeting with the change project manager. The project manager is an executor – a high hands change leader. Once again, the supervisor will fail if the focus is on people. The supervisor needs to talk like the project manager would talk. The supervisor should be pragmatic and talk efficiency. And the supervisor needs to get feedback on whether the project manager sees the practical impact and gets the plan for the change.

Bottom line: To make change happen, know yourself and know your people so you can communicate in their language. In other words, the high heart leader needs to communicate from the perspective of the target audience – head talk for head people and hands talk for hands people.

Being people-focused means giving them what they want,  not what you want to give. Talk their talk to create dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

not what you want to give. Talk their talk to create dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

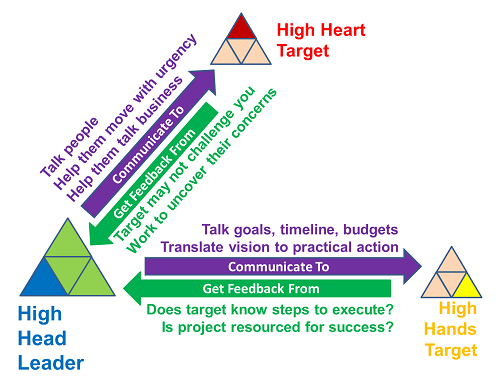

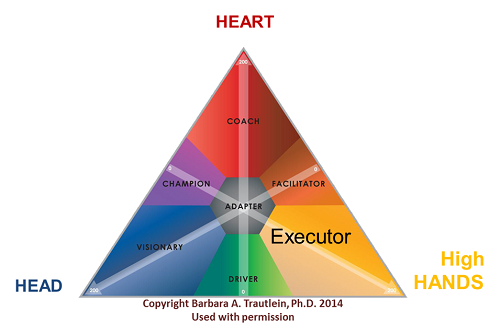

The Platinum Rule for “Just Do It” Change Leaders

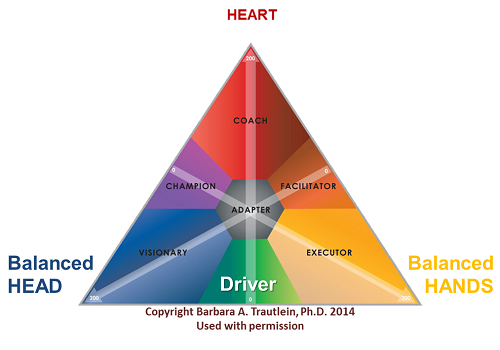

Hands-oriented leaders make the change happen on time, to budget and to specifications. They are the people you turn to when you want change to take hold. They “just do it”.

In Barbara Trautlein’s model of change intelligence (CQ), executors, drivers and facilitators are high hands change leaders.

But Enough About You. What About Them?

Self-awareness about your CQ style is important, but it is only the starting point. To be effective in executing change, you must know the CQ style of the people you work with to understand how to best interact with them. Here’s a key principle:

People don’t think much about your CQ style. People want to be treated according to their CQ style.Trautlein refers to this as the platinum rule: don’t treat people like you want to be treated (the golden rule). Treat people like they want to be treated.

Let’s consider a project manager (PM) who is a high hands change leader – an executor. The project manager keeps things on schedule, under budget and to specification. With other high hands people, the project manager will communicate on the same wave length – what’s next and what’s the impact.

However, when the PM meets with a senior executive who is a visionary (high head change leader), the PM may miscommunicate if the focus is strictly on tasks. Executives want to know about the project’s pace and bottom line impact, without all the details. They also want to see how the project fits into the overall vision for change. The PM needs to be more focused on the vision of the change and to get feedback from the executive on the overall vision for change.

In the same way, when the high hands project manager meets with a high heart supervisor, the PM needs to be more people oriented. The PM should deliberately reach out more often to the supervisor. Conversations should include celebrating success and not just project updates. The PM also needs to actively seek the supervisor’s participation and check in on the project’s impact on the people on the front lines.

Bottom line: To make change happen, know the people you work with so you can communicate in their language. A high hands leader needs to communicate from the perspective of the target audience. Use heart-targeted communication with heart-focused people and head-targeted communication for head-focused people.

Communicate according to the platinum rule and you will take a powerful step toward dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

Communicate according to the platinum rule and you will take a powerful step toward dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

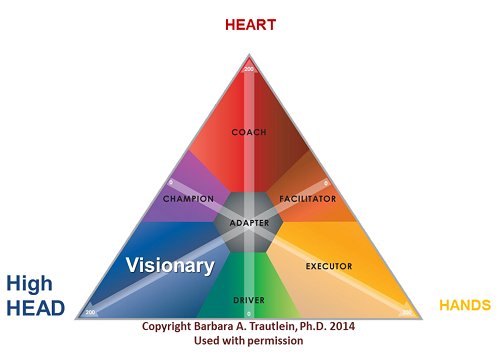

The Platinum Rule for Visionary Change Leaders

Head-oriented leaders are strategic and purpose-oriented, adept at inspiring others toward the bright new future. They serve as a lighthouse to help guide others toward the long-term vision for change. In Barbara Trautlein’s model of change intelligence (CQ), visionaries, drivers, and champions are high head change leaders.

But Enough About You. What About Them?

Self-awareness about your CQ style is important, but it is only the starting point. To be effective in leading change with a variety of people, you must know their CQ and how to best interact with them. Here’s a key principle:

People don’t think much about your CQ style. People want to be treated according to their CQ style.Trautlein refers to this as the platinum rule: don’t treat people like you want to be treated (the golden rule). Treat people like they want to be treated.

Let’s consider a CEO who is a high head change leader – a visionary. In the executive suites, surrounded by like-minded visionaries, the CEO’s conversation will be strategic, looking at change from 20,000 feet. But if we take the elevator down to ground level, the change looks different. Like the emperor in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale of The Emperor’s New Clothes, the power distance between the executive suite and the rest of the organization can create communication disconnects. To implement lasting change, the CEO must adapt to high heart and high hands target audiences.

With high-heart people, the CEO needs to talk about how people are handling the change and help high heart people talk business. Because of the difference in power between executives and supervisors, the visionary CEO will need to be especially adept at coaching the target audience to raise concerns.

With high hands people like project managers, the CEO must help translate the overall vision for change into practical actions. To do this, the CEO needs to be ready to talk details. And, a visionary executive needs to ensure that the project manager knows what’s next and has the resources to make the change happen.

A visionary CEO may be tempted to state the vision for the change and move on to the next big decision. That violates the platinum rule.

You must look at the change from the perspective of your audience. And you cannot rely on your subordinates to correct your communication oversights. Your power and authority will tend to insulate you from your audiences. You will only know the depth of your mistake when the change fails.

Bottom line: To make change happen, know yourself and know your people so you can communicate in their language. Visionary change leaders have to guard against wearing the emperor’s new clothes. Get in the trenches. Get to know the people and the project details so you can connect people and tasks with your vision for change.

Then, you will be ready for dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

Then, you will be ready for dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

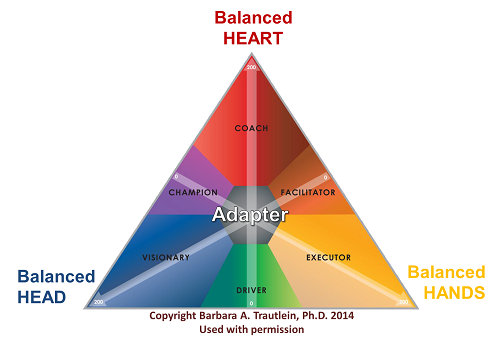

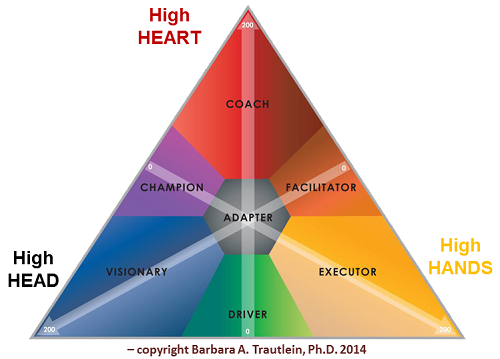

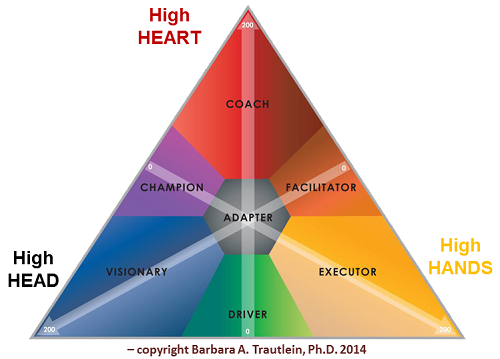

Change Intelligence: Adapters

Change intelligence (CQ) highlights the need to focus on hands, heart and head for successful change. There are three dynamic duos – CQ styles that complement each other:

But there is a simpler way. If heart, head and hands are all necessary for leading change, wouldn’t the ideal change leader style combine all three?

Change Leader: The Adpater

Adapters are balanced, with moderate level of heart (care for others), head (thought leadership) and hands (task leadership).

Barbara Trautlein describes adapters as flexible and open to new experiences. They embrace change wholeheartedly. The adapters motto is “Looks Exciting – Let’s All Try It!” They are team players – interactive and willing to hammer out a compromise. Adapters are politically aware, navigating organizational minefields that thwart other change leaders. And, they have strength in each of the three dimensions of change leadership.

So, the adapter must be the ideal style for change leaders, right?

Well, no.

Adapter is not the best style for all change leaders. Here are three reasons:

1. Adapters have real shortcomings. They can be seen as unpredictable and inconsistent. They are often overly political, even wily. And, they will talk your ear off at times, attempting to get a workable compromise.

I know the shortcomings of adapters well, because I am one. My CQ profile is adapter (leaning toward driver), and I have been guilty of all these shortcomings. One of my 360 reports said “I never know which Allen will show up at work today.” Based on that feedback, I now make a conscious effort to balance my openness with constancy of purpose. But organizational politics and my desire to keep things moving can bring out the chameleon in me.

2. Being overly flexible is not always ideal for a change leader. In a post on The Leadership Paradox of Principled Moderation, I highlighted the limitations of moderation and inconsistency.

Petronius said “Moderation in all things, including moderation.” Some people refer to this as a paradox. I see moderate moderation as a gentle warning of the dangers of absolute relativity. As a leader, at times you need to be a rock in the storm. You have to take a principled stand. The people you lead expect consistency in your behavior.

3. The adapter is a generalist, but often change leadership needs a specialist. The adapter may be able to articulate a vision for change, but the visionary can focus energy on change with more intensity. The adapter can create a work plan, but the executor creates a robust plan with more contingencies and better scorecards. The adapter can build relationships, but the coach cares more deeply about his or her people.

Sometimes the adapter is the best change leader. Their personal flexibility allows them to do many things well. But often the adapter works even better within a team that includes leaders with diverse CQ profiles.

If it takes a village to raise a child, then it takes a team to lead change. Adapters can team up with leaders with diverse CQ profiles. By working with people who are less adaptable, the adapter will be a better change leader.

Moving from solo change leader to a team with different CQ styles shouldn’t be too big of a change. For an adapter.

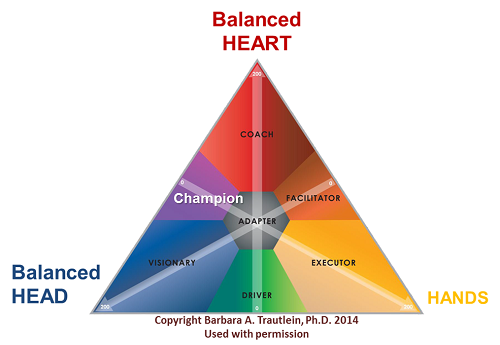

Change Intelligence: Executors and Champions

Change intelligence highlights the need to focus on hands, heart and head for successful change. In today’s post, we will start with the hands – task leadership in change. (By the end, we will cover the heart and head as well.)

Change needs action-oriented leaders. Someone has to plan the work, watch the budget and manage the schedule to keep a change project on target. In other words, change needs executors.

Change Leader: The Executor

Executors are high hands, focusing on task leadership.

Barbara Trautlein describes executors as systematic planners who are dependable, proficient and efficient. Executors plan the work and then work the plan. They focus on what is doable and they pride themselves on staying on time and on task.

Barbara Trautlein describes executors as systematic planners who are dependable, proficient and efficient. Executors plan the work and then work the plan. They focus on what is doable and they pride themselves on staying on time and on task.

The executor is master of the details. If specifications change, they work out all the implications. If there’s a delay, they know the task interdependencies and the impact on delivery dates. If an unexpected cost is incurred, they dig into the budget and the contract to tack down what happened.

Executors have blind spots, of course. They can be shortsighted, losing site of the vision for the change. Executors can also be narrow, data-bound perfectionists. They can bulldoze people to stay on time, on task and under budget. Because of these blindspots, executors might need help with the heart and head aspects of change leadership.

Leader: The Champion

Across the CQ triangle from the executor, we find the champion, a change leader who is balanced on heart and head.

Trautleins’s motto for champions is “Together We Can Make It Happen!” Champions are compelling and charismatic. They are often powerful and effective communicators. They are audience centered and they stay on message. They create insight and get buy-in from people for the change. Champions are true cheerleaders for change.

Champions also have blind spots. Champions can get bored by the details. They can be overly optimistic and impractical – all cheerleader when a little pragmatism is needed. And, champions are attracted to the flavor of the month. They often move on to the next trend without finishing strong.

The champion’s ability to keeping people motivated toward the bright new future helps balance out the executor’s weaknesses. And, the champion’s weakness on details and lack of a strong finish are compensated by the executor’s focus on planning and execution. These tradeoffs make the executor and the champion a dynamic duo of change leadership.

What if the executor can’t pair up with a champion? An executor can look for two or more partners in change.

You want at least one visionary or driver to provide thought leadership. Then, the executor’s work plan will be linked to the vision for change.

You also want at least one coach or facilitator to provide relational leadership to ensure people are cared for in the midst of change.

Bottom line: Your change leaders can be a dynamic duo of executor and champion, or they can be a bigger team. The key is to have leaders who focus on hands, head and heart – work plans, vision and engagement – to make change happen. Anything less is a plan for failure.

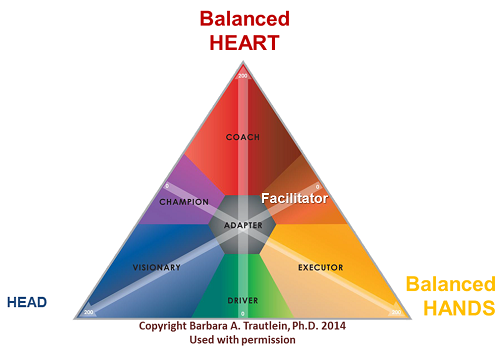

Change Intelligence: Visionaries and Facilitators

As we continue to think about change intelligence, today we’ll look at the dynamic duo of “visionary” and “facilitator”.

Change Leader: The Visionary

Barbara Trautlein describes the visionary as strategic, futuristic and purpose-oriented. In other words, he or she is a high head change leader.

Visionary leaders are important because vision is essential for successful change. In Kotter’s eight steps for planned change, three are about vision:

3. Create a vision. A powerful vision creates a brief and memorable summary of the change.

4. Communicate the vision. Engage your employees in dialogue about the change. Underscore the key points and get their feedback, insight and creativity.

5. Empower others to act on the vision. Encourage people to act without your tight control. Your vision should set direction and boundaries for the change. Let others sweat the details.

Visionary leaders are masters of these steps. They create focused energy for change, much like a Fresnel lens in a light house.

A lighthouse gives clear direction. But a lighthouse cannot bring a ship into port by itself. The ship needs sailors and charts. In the same way, a visionary cannot succeed just by focusing on the “head” aspects of change. Vision gets the ball rolling, but people and planning put the change into action.

In Kotter’s eight steps for planned change, the last three steps are more about heart and hands (or people and plans) than head and vision:

6. Plan for and create short-term wins.

7. Consolidate improvements and produce still more change.

8. Institutionalize new approaches.

Visionaries may falter in the heart dimension of change by wanting to move sooner than people are ready. They may be weaker in the hands dimension, lacking detailed planning and follow-through.

Visionaries should not try to lead change by themselves. A high-head visionary coach can partner with someone who is strong in heart and hands.

Change Leader: The Facilitator

Looking across the CQ triangle from the visionary, we find the facilitator, a change leader who is balanced on heart and hands.

Trautleins’s motto for a facilitator is “Lean on Me – I’m Here to Help”. The facilitator is involved, helpful, resourceful and practical. They are strong on heart, being a good listener like a coach. And they are strong on hands, getting stuff done like an executor.

Trautleins’s motto for a facilitator is “Lean on Me – I’m Here to Help”. The facilitator is involved, helpful, resourceful and practical. They are strong on heart, being a good listener like a coach. And they are strong on hands, getting stuff done like an executor.

The facilitator’s strengths perfectly complement the coach’s weaknesses. And, the facilitator’s weaknesses – too tactical, lack of strategic leadership, hesitant to confront others – are compensated by the visionary’s focus on the head. These tradeoffs make the visionary and the facilitator our second dynamic duo of change leadership. (Coach and driver were the first dynamic duo.)

What if the visionary can’t pair up with a facilitator to lead the change? A visionary can look for two or more partners in change. You want at least one executor or driver to provide task leadership and at least one coach or champion to provide relational leadership. Then, the visionary’s head will be balanced with the hands and hearts of others to lead the ship of change safely to port.

This post is dedicated to CWO4 Harry B. Slade, USCGR, who started with the Coast Guard in WWII and ended in 1984 managing aids to navigation, including light houses with Fresnel lens. Semper Paratus!

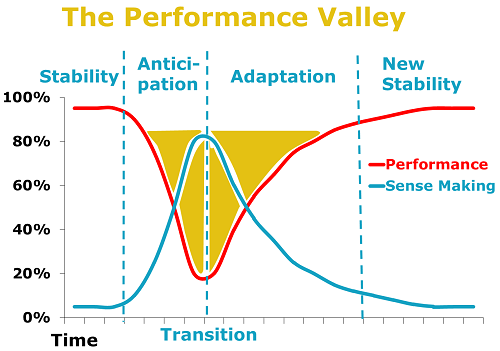

Change Intelligence: Coaches and Drivers

In this blog series on change intelligence, we’ll look at the styles of “coach” and “driver” today.

Change can be discouraging. Change require sense-making, and sense-making requires emotional and cognitive energy. Being deep in the performance valley increases the stress of the change.

When you are deep in the performance valley of change, who walks with you? In my circle of trusted advisors, I have several people who act as change coaches. They focus on my perspective, my reactions and my feelings in the crisis. In other words, they focus on my heart.

Change Leader: The Coach

Barbara Trautlein’s model of change intelligence categorizes coaches as heart-oriented change leaders. They help motivate and support others in the midst of change.

By focusing on the heart, coaches care for people. They are great to have on the team during change. They are positive, encouraging and tolerant. They often have a great sense of humor. They will go into the performance valley and keep everyone together.

However, coaches may need a little help on head. For example, they may not be communicating the vision for today’s change or scanning for future change opportunities. Coaches should seek feedback from senior executives on the vision for change. And, they should be mindful of the need to analyze the future.

Coaches may also be weaker on hands. They may not have a detailed plan for the change. And, they may not hold themselves and others accountable for progress. Coaches should fill out their toolbox with planning tools. They should also set SMART goals for themselves and others.

Coaches do not have to lead change by themselves. A high-heart coach can partner with someone who is strong in head and hands.

Change Leader: The Driver

Looking across the CQ triangle from the coach, we find the driver, a change leader who is balanced on head and hands.

When it comes to change leadership, a driver’s approach is “Just Do It”. The driver is confident, pragmatic and focused. They plan the work and then work the plan. The driver’s focus perfectly complements the coach’s weaknesses. And, the driver’s weaknesses – stubbornness, over-control, lack of listening – are compensated by the coach’s focus on the heart. These tradeoffs make the coach and the driver our first dynamic duo of change leadership.

What if the coach can’t pair up with a driver to lead the change? A coach can look for two or more partners in change. You want at least one visionary or champion to provide thought leadership and at least one executor or facilitator to provide task leadership. Then, the coach’s heart will be balanced with head and hands to get everyone through the performance valley of change quickly and effectively.

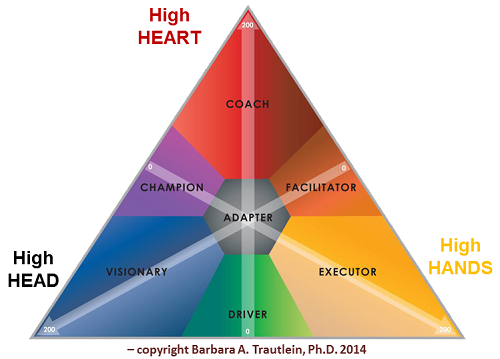

Change Intelligence Quotient

Given that 70% of large scale changes fail, we need to slant the odds in favor of success. We need better leadership for change.

So, what makes someone good at leading change? Articulating the vision for the change? Connecting with people in the trenches of change? Technical skills, such as project management or design? And, the answer is . . .

[drum roll]

. . . Yes!

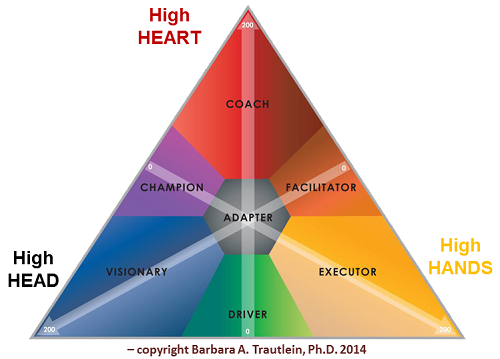

Barbara Trautlein’s research on Change Intelligence: Using the Power of CQ to Lead Change that Sticks suggests three key dimensions to leading change: head, hands and heart.

Head-oriented leaders focus on the long term vision. They are strategic and purpose-oriented, adept at inspiring others toward the bright new future.

Heart-oriented leaders help engage and care for others in the midst of change. They are motivational and supportive coaches.

Hands-oriented leaders make the change happen on time, to budget and to specifications. They plan the work and then work the plan.

Some change leaders are laser focused on just one of the three – head, heart or hands. Other leaders blend two of the perspectives. And, adapters have a balance of head, heart and hands. Taking all the possibilities, there are seven styles of change intelligence.

So, which style is best? Like many things in life, leadership and organizational effectiveness, the answer depends on the situation.

Sometimes a coach engages the heart, but needs a driver to get stuff done.

A visionary may trigger the change while a facilitator is needed to bring people and tasks to the successful end point.

An executor can manage the project details but may need a champion to create the vision and provide the heart to engage people in the long term vision.

And, do not think the adapter is somehow the perfect blend. My style is adapter, leaning toward driver. While my flexibility is valuable in many change environments, sometimes I confuse people by seeming mercurial.

In other words, all seven styles have advantages and drawbacks. What matters is knowing yourself and others, then combining styles and adjusting to the situation to maximize the odds of success for your change efforts. Trautlein calls ability CQ:

CQ (or Change Intelligence) is the awareness of one’s own Change Leader Style, and the ability to adapt one’s style to be optimally effective in leading change across a variety of people and situations.I am on record saying that emotional intelligence is dumb. Why would I write about change intelligence?

Emotional intelligence (or EQ) implies an ability. There is a high and a low, and the high is obviously better. The problem I see is the implication that EQ imposes some upper limit on a leaders emotional capabilities. I prefer to talk about managing emotions, since that is something all leaders can master.

CQ is built on the appreciation of three change leadership focal points – head, heart and hands. There is no judgment implied that one is superior. All three focal points are essential. All seven styles are valuable.

Over the next few weeks, I will be blogging about each of the seven CQ styles – the good things as well as the pitfalls and pratfalls that each style can pose for change leaders. My intent is to use change intelligence to help you know yourself better and to know the other people facing change.

Bottom line: Know yourself, know the people around you and know what challenges you face in a change project. That trick, that knowledge, is a powerful step toward dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

Spoiling Good Goals with Bad Metrics

The Veteran’s Health Administration exists to give the best possible medical care to America’s military veterans. One way to do this is to set goals for standards of care. But the VHA’s good goals were spoiled with bad metrics. According to the Washington Post:

The agency has made it a goal to schedule appointments for veterans seeking medical care within 30 days. But the interim IG report found that in the 226-case sample, the average wait for a veteran seeking a first appointment was 115 days, a period officials allegedly tried to hide by placing veterans on “secret lists” until an appointment could be found in the appropriate time frame.

“We are finding that inappropriate scheduling practices are a systemic problem nationwide,” the report stated. “We have identified multiple types of scheduling practices not in compliance with VHA [Veterans Health Administration] policy.”

The goal to schedule timely appointments was important to the VHA’s mission. It was specific, measurable and time-bound. Yet, the behavior it triggered was not better healthcare for veterans. Instead, multiple leaders and employees at multiple VHA sites cheated the system by distorting the metrics. Why? And, what can leaders do to avoid making a similar mess of their good goals?

A Recipe for Goals

Goals done right can elevate the performance of your team. Recently, I proposed a recipe for leaders to make goals more effective:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Part of being realistic is making sure none of your employees have too many goals.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Create goal-specific metrics to further shape and refine behavior.

Avoid goal blindness. Goals can focus attention and energy too much, causing people to miss other important issues. Use principled leadership, shift your focus periodically and resource goals properly to avoid goal-induced blindness.

If your take steps to avoid goal blindness, and you help your team create goals that are SMART, coordinated and backed by metrics, what could go wrong?

Missing Ingredients Spoil the Dish

Forgetting the yeast will waste a batch of bread, and skipping the sugar will ruin a pitcher of lemonade. The VHA scheduling goal seems to have been missing a few ingredients. The goal was specific, measurable and time-bound, but was it actionable and realistic?

For a goal to be actionable and realistic, those accountable for the goal must expect to succeed if they take the right action. The demand for VHA services has increased with the influx of new veterans and the aging of Vietnam era veterans. In many cases, demand for services has exceeded capacity. There just aren’t enough doctors, nurses, therapists and facilities to care for the patients.

If you set impossible goals, expect failure. The failure may show up right away in the form of missed goals and demotivated employees. Or the failure may be hidden for a while by gaming the metrics. But the failure is inevitable if the goals are not actionable and realistic.

Avoid the Mess

What could can leaders do to avoid making a mess with metrics?

Trust but verify. Metrics must be valid and reliable. Leaders should be trusting, but they should also audit metrics to make sure they are working.

Get experts to review your metrics. Verify metrics with other data, such as checking quality data with customer surveys. Be especially vigilant if people provide their own metrics.

Get experts to review your metrics. Verify metrics with other data, such as checking quality data with customer surveys. Be especially vigilant if people provide their own metrics.

Treat missed goals as a signal. It is tempting for leaders to blame poor performance on their followers. Yet, when goals are missed, they can signal a system failure.

If an employee misses a goal, don’t just reprimand, threaten or punish. Instead, trigger intelligent change. Talk about the causes of performance and help create an action plan to make a difference.

If an employee misses a goal, don’t just reprimand, threaten or punish. Instead, trigger intelligent change. Talk about the causes of performance and help create an action plan to make a difference.

Don’t assume all the actions will be by your employees. As the leader, you may have to create a more realistic goal or provide the resources to make success possible. To fix the VHA mess, Congress should demand action by the Veterans Administration. They should also fund the employees and facilities needed for success.

Bottom Line: As a leader, your job is not done when you set goals with your team. You have to provide resources to your employees so the goals are actionable and realistic. You have to make sure the metrics are valid and reliable. And, you have to respond to missed goals with dialogue and insight. Otherwise, your metrics can make a mess of good goals.

Dedicated to Joseph W. Slade, Sr. and Dallas Wiggins U.S. Army Veterans Patients of the Hampton VA Hospital All veterans deserve the level of care these soldiers received.

Got a Goal? Get A Metric!

Goals are powerful leadership tools to focus attention and effort. But goals are incomplete without a measure of success.

Basics of Goal Setting

As a leader, goal setting is an essential part of your leadership toolbox. Like any tool, you have to use goals right:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Part of being realistic is making sure none of your employees have too many goals.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Give goal-specific feedback to further shape and refine behavior. In today’s post, let’s discuss how metrics work with goals to energize behavior.

A SMART Goal Needs a Metric

A metric puts a ruler on your goal. It provides a number or a category (yes/no) on the behavior or outcome defined by the goal. If your goal is specific, measurable and time-bound, then a metric should naturally follow.

But a metric is not just some “logical” aspect of a SMART goal. A metric provides a motivational complement to a goal. A goal should focus attention and effort to drive performance. The metric shows whether the performance meets expectations. If all is well – the metric shows the goal is being accomplished – then the person should continue their efforts.

If the metric shows all is not well – the goal is not being accomplished – then the person needs to change something. Maybe they need more effort – working harder. Maybe they need different effort – working smarter. Maybe they need better support from you as their leader – better equipment, a bigger budget, just-in-time training, better performance coaching, or whatever.

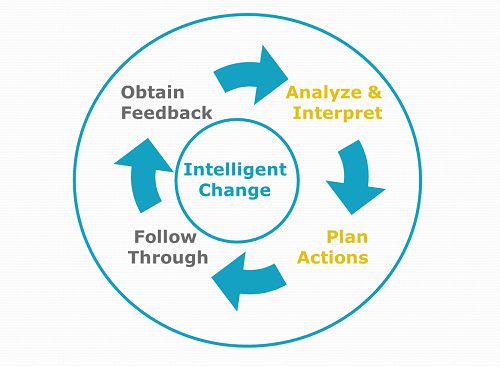

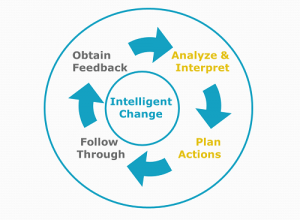

Missing a goal should trigger a cycle of intelligent change:

The initial feedback (unmet goal) . . .

should lead the employee and the leader to analyze and interpret the causes . . .

plan actions to improve performance to the goal and . . .

then follow through with the actions to improve performance.

If the change is simple and easy, one turn of the wheel may be enough. A sales person contacts more prospects and meets their sales quota. Or an operations manager schedules smaller and more frequent deliveries of stock to reduce inventory carrying costs. The simple and easy change drives improved performance, the goal is met, and all is well.

Many times, the change will not be easy and simple. For example, a general manager may miss their profitability goal or a brand manager may miss a market share goal. If the needed changes are complex or difficult, the planned actions may need to be many mini-experiments:

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

It all starts with a SMART goal supported by the right metric. If a goal provides the power – the effort and attention to drive performance – then a metric provides the measurement to guide the continued application of the power.

In my workshop, I have a number of tools. I am especially fond of power saws. I was coached to “Measure twice. Cut once.” In other words, have your ruler in place before applying the power of the saw.

Bottom line: A metric is a tool of leadership that provides a motivational complement to a goal. Just like you should not use a saw without a ruler, you should not set a goal without a metric.