When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Smart Goals

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders set goals for themselves and others. The most powerful goals tend to be specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Here are my thoughts on how to set smart goals:

Specific – the goal states a specific outcome or action. If your goals are stated only as outcomes, there may be no obvious steps to take. You don’t want to be like the basketball coach who talks about winning but has no plan for today’s practice. If all of your goals are actions, you can get disconnected from your ultimate purpose, like the basketball coach who focuses only on holding a great practice. I encourage my clients to set a mix of outcome goals and action goals, covering both the end to be achieved and the means to that end.

Measurable – the goal can be assessed against an objective standard. We tend to value what we measure and measure what we value. Without measures, your goal is light-weight. The measures can be hard, in the form of objective numbers. Numeric metrics are straightforward, but easy to measure does not equal important. Your measures may need to be soft, in the form of assessments of key stakeholders. And some measures are binary: Did the desired activity or outcome happen (yes or no)? Different goals require different metrics, but all goals should be measurable.

Actionable – the goal can be acted on by the person who holds the goal. Your goals are powerful only if you can personally take steps to accomplish the goal. As a leader, set goals with your team that are in their realm of possiblity. Otherwise, you will undermine their motivation and your credibility.

Realistic – the goal is difficult but attainable. Harder goals increase performance. But goal difficulty has limits. When a goal becomes unrealistic, its power disappears. When setting goals for ourselves, you should think through your odds of success. When setting goals with others, have an open two-way discussion of the goal to get the level of difficulty right. Difficult goals are good, but they must be attainable.

Timebound – the goal has clear timing, either a date or a rate. For one-time goals, use a due date. “I will accomplish this action by April 1 of next year.” For ongoing goals, use a rate of action or outcome. “I will sell $100,000 of new consulting business per month.” Without a date or rate, a goal is not specific or difficult.

With all five smart features, your goals will have maximum impact. And, all five feature should reinforce each other. The specific actions should be realistic, the metrics should have a date or rate, etc.

It is possible to go overboard – to be too smart for your own good. With my leadership coaching clients, less is usually more. At first, I encourage them to focus on just one or two behaviors to change. Taking on too many changes creates frustration rather than change. We often start with goals that are general. For example, a client increasing visibility might start with “Notice how much airtime I take up in meetings.” This is not specific, but sometimes that is all that is needed to trigger change. If a stronger trigger is needed, we move to a more specific goal, such as “I will speak up twice in every meeting.” If that doesn’t works, we can move to an even smarter goal, such as “In Monday’s meeting, I will comment twice on product quality. In advance, I will analyze some data and prepare a customer story.”

Almost every goal could benefit from being a bit smarter. Yet consider what works for you. Some people thrive on smart goals tightly linked to their life purpose and their daily schedule. Others need nothing more than a Post-it reminder. And, once your goal is in play, notice how it works for you. If you are making progress and accomplishing what you want, that goal is right for you. If your goal is not working, consider making your goal smarter.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

When leading others, it is essential to personalize goals. For example, at the beginning of the performance review cycle, use lots of participation in setting goals. Don’t just exchange drafts of the performance plan. Have a detailed discussion of what works. Check to make sure your team members believe their goals are actionable and realistic, because it is their acceptance of the goal that will drive performance.

It is also important to agree on metrics and time for each goal at the beginning. Then, during the peformance review, you and your team member will be on the same page with feedback.

Bottom line: You should set specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound goals, for yourself and for others. When setting goals with others, have lots of dialogue. Be smart – create dialogue, insight and powerful goals to drive performance.

Negotiation: The Dance of Requests and Offers

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Requests and offers make up the dance of negotiation. An offer is the mirror image of a request. With a request, you are triggering action by the other person. With an offer, you are proposing to act for the other person. An offer requires a valid response, just like a request: Yes, No, Counter Offer or Decide Later. It is the back and forth of requests paired with offers and offers followed by counter offers that creates the dance of negotation.

A succesful negotiation leads to an agreement that meets the interests of both you and the other person. Bill Ury distinguishes several forms of negotiation:

Hard positional bargaining. “Participants are adversaries. The goal is victory. Demand concessions as a condition of the relationship. Distrust others. Dig in to your position. Make threats.”

Soft positional bargaining. “Participants are friends. The goal is agreement. Make concessions to cultivate the relationship. Trust others. Change your position easily. Make offers.”

Positional bargaining, hard or soft, locks in positions and makes the negotation a win-lose game. Positional bargaining tends to produce unwise agreements, inefficiency in the bargaining process and stress in an ongoing relationship. I have purchased a number of cars using hard positional bargaining. Even if we reach an agreement, the bargaining is adversarial, long and dissatisfying, at least for me as a customer.

Principled negotiation is when the parties go beyond positions to the underlying interests and look for win-win solutions. Four steps will help you do this:

- People: Separate the people from the problem.

- Interests: Focus on interests, not positions.

- Options: Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do.

- Criteria: Insist that the results be based on some objective standard.

I use principled bargaining to buy and sell cars. For my last car purchase, I looked for a dealer who would agree to principled negotiation. Over the phone, we agreed to use a price that was $250 over dealer cost. The face-to-face negotiation was amicable, efficient and mutually satisfactory.

Is principled negotiation better to hard or soft bargaining? It depends. I keep all three forms of bargaining in my leadership tool box. I tend to use principled negotiation in ongoing relationships dealing with a substantive issue. Negotiating on principles builds relationships while building agreements. I may use hard positional bargaining when there is no long term relationship and the other person is treating the situation as a win-lose game. I may use soft positional bargaining when the relationship is key, the other person is passionate about their position and I am flexible on the issue.

If you practice the steps of requests and offers, you will be able to dance to a variety of music. Make smart requests. Make big asks. Give and demand valid responses. You can adjust your negotiation style to the heavy metal of hard positional bargaining, the swing dancing of soft positional bargaining or the long term romantic dance of positional bargaining. If you influence the play list, you may be able to set the style of negotiation you prefer. Otherwise, negotiate to the music being played.

Making Unreasonable Requests: The Big Ask

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Usually, I recommend SMART requests: requests that are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. But should a leader’s requests always be realistic? According to Kim Krisco, a leader accelerates change with unreasonable requests:

The primary speech act that creates action and increases velocity is the request. The more requests, the more action and change. The more unreasonable the requests, the greater the change. Indeed, you might say that the function of a leader is to make unreasonable requests.

An unreasonable request is a big ask. When should leaders make the big ask?

Bottom line: I believe you should use the big ask rarely, and well.

A big ask is a stretch for the other party. Make sure you have the creditability to make it stick. If you make the big ask too often, you will undermine your credibility as a leader and your future requests will have less impact. You must prove that signing up for your big ask is a good idea – your request will pay off for the organization and for the other person. A big ask, if accepted by the other party and mutually beneficial when fulfilled, can add to your creditability. If the check is accepted, and it cashes, you get another blank check.

You must be especially well prepared for the big ask. The big ask should be given only when you are at a peak level of leadership presence – passion and purpose, emotions, body, relationships all need to be in congruence with the big ask.

The big ask is a declaration which can create a bold, new future. In 1961, John Kennedy declared “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” Most requests should be realistic. But realistic requests would not have gotten Neil Armstrong to the moon in 1969. The big ask should be used rarely, and well.

Leaders should be able to make the big ask. They should also encourage risk taking by supporting the big asks of others. Soon after I started at IBM, my manager said to me “Allen, you get one blank check. If I don’t agree and you insist, I will back you. But only once. If that check cashes, I will give you another blank check.” In effect, he advanced decision making credibility to me, despite my lack of experience. He encouraged me to make the big ask, but to make it rarely and well.

Do you insist that people prove their credibility before you will take a risk on their decision making? Try advancing some decision credit instead. It can be scary to give up control, so you can start with just one blank check. See what happens when you back someone’s big ask. The spark of initiative that results may flame into a bonfire of innovation.

Response Required

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders use requests to trigger action. If your requests don’t trigger the action you want, you may need to make smart requests. But even the most carefully crafted request requires discipline in listening for the response.

Bottom line: For all your requests, insist on one of these responses:

1. Yes

2. No

3. Counter offer

4. Decide later

As Kim Krisco says, “If you let someone give you anything except one of those responses, there is a good chance that the action you want and need will not be forthcoming.“ A non-response, changing the topic or refusing to answer are not valid responses. As a leader, insist on “yes”, “no”, an offer to negotiate or a commitment to decide later. Demand a valid response out of self-respect and out of respect for the other person, because a request requires a valid response.

If you will not accept “no” as a response, what you are saying may be a command or a demand, but it is not a request. Requests may be stated politely while commands and demands often use more forceful language. However, commands may also be phrased quite politely. For a Navy ensign, the statement “The captain requests the pleasure of your presence on the bridge” is clearly a command, because the captain has substantial legitimate power over the ensign. The polite phrasing may be an attempt to soften the command, or it may actually reinforce the power differential. Either way, the ensign will rush to the bridge.

Like a command, a demand does not leave room for “no”. If a command is based on formal authority, a demand is based on coercion. A demand has an edge to it. “Do what I want or else . . . .” The “or else . . .” may be stated boldly in the form of a threat. Or it may be implied with language such as “I have the right to . . . .” Insisting on your rights implies that you can call for backup to enforce your rights, such the police or Human Resources. Either way, a demand lays out the choice of acquiesence or escalation.

This is not to say that a request, once made and rejected, is forever dead. An influential leader may test a negative response. After hearing “No,” the leader can ask “Why not?” or make a counter offer. Yet, a leader will allow the recipient to refuse a request. Being willing to accept “No” as a valid answer is fundamental to your respect and authenticity as a leader.

As leaders, we draw on our interpersonal influence, not formal authority, coercion or rights. We use requests to trigger action, not commands or demands. We may find ourselves in other roles – as a manager with legitimate authority or an employee with rights – and in those roles we may choose to use commands or demands. But if you are acting as a leader, use requests to trigger action. Insist on hearing “yes”, “no”, an offer to negotiate or a commitment to decide later. You may not always get what you want, but you increase the odds when you insist on a valid response to your requests.

Making Smart Requests

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Leaders use requests to trigger action. As Chalmers Brothers says:

We make requests when we have an assessment that the future is going to unfold in a certain way, and we don’t like that. We want the future to unfold in a different way than it seems to be heading by itself, and in order to put things in action to bring this about, we make a request.

Effective requests require discipline by the leader in how the request is made and what answers the leader will accept. In another post, we will think about what answers a leader should accept for a request. But today, let’s look at how to phrase your requests for more influence.

Here’s the bottom line: If your requests don’t trigger the action you want, try making your requests SMART – specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time bound.

Specific – the request states a specific behavior or outcome to be achieved. To get more action, our request for better responsiveness could be phrased as “I would like all customer voice mails to be answered promptly.” This request defines the desired behavior more specifically.

Measurable – As with smart goals, we value what we measure and measure what we value. A request that cannot be measured will have less impact.

Actionable – the request can be acted on by the person who receives the request.

Realistic – the request can be actually met. An actionable and realistic request is something the other party can reasonably commit to fulfilling.

Time-bound – the request should have clear timing, usually either in the form of a rate of accomplishment or a deadline. A rate of accomplishment might be “I would like to have you contact 10 customers a week for feedback.” A deadline might be “I would like each person in the support team to answer all their voice mails by the end of the day they are received.”

Be specific about who will achieve the outcome. “I would like us to answer all customer e-mails promptly” implies that the you will do some or all of the answering. “I would like you to answer all customer emails promptly” makes the responsibility more specific. The difference between “us” and “you” is an example of diffusion of responsibility. In making a request, be specific about who will act. Diffusion of responsibility increases with group size , so the leader making a request to a group needs to be even more clear in targeting the request.

Make all of your requests actionable and realistic. Unreasonable requests can undermine your credibility and alienate your audience. It does not matter how reasonable you think your request is – the key is whether the person receiving the request believes they can realistically take action to accomplish what you ask. Keep your ears and eyes open to see how your request lands with the other person. Adjust your request – timing or quantity – or negotiate additional resources to help the other person expect to be able to do what you ask.

Even a smart request can fail if you give the other person a ready excuse for ignoring your request. In general, a request has more power when it stands alone. A stand-alone request takes courage, especially in allowing the request to echo in silence. Leaders need to exercise courage, and often that means using a powerful request and waiting for the other party to respond.

How smart do your requests need to be? Smart enough to accomplish your purposes. If you make a vague request and it triggers the action you want, great! No need to tinker with success. On the other hand, if your requests are not working, try making them smarter. You may not always get the action you want, but you increase the odds with a smart request.

The Power of &

By Dr. Allen Slade, ACC

Why Slade & Associates? Why not Allen Slade, LLC or some other name for this professional services firm? When I formed Slade & Associates in 1988, I knew my work. Whether I was training, writing, teaching or consulting, my best work happened with others. This is not a personality issue, since I am somewhat of an introvert. Instead, my work improves with the power of the team, the power of dialogue, the power of shared accountability. The power of &.

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” Our internal thinking can be a bit chaotic and illogical. When we share those thoughts with others, our thinking improves. The rules of language, the articulation of logic and the fear of looking foolish impose a discipline on our thinking that improves our ideas. Once we share our ideas, the power of dialogue kicks in. The people around us can sharpen our ideas with powerful questions, new information or with alternative ideas. The richness of the dialogue drives the quality of the insights.

For collaboration to work well, we need to work with people who we value and trust. We need to have people both challenge our thinking and support our work. At Slade & Associates, the people I choose to work with – my associates – make me better. They are confident, committed, and competent. They make me better. Together, we make our clients better.

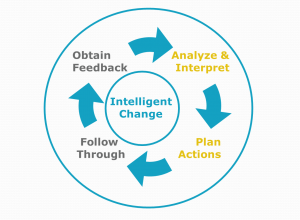

The Slade & Associates mission is creating “Dialogue & Insight for Intelligent Change”. (Can you tell I like ampersands? This post could have been titled “The Power of & & &”.) We do not put on our expert armor when working with our clients. We don’t assume the consultant or coach has all the answers. Instead, my associates and I assume our clients are the experts in their own situation. We help move the dialogue along to create insight. We ask powerful questions. We bring in new concepts and new data. We light the match. Then, with our clients, we fan the flames to create insight to ignite intelligent change.

Do the people around you make you better? Does your thinking improve when you share it? If not, consider what is blocking the power of & for you.

You may not have the supportive environment you need for the power of &. Some work environments are too competitive for collaboration to really work. At Microsoft, many of my fellow directors had sharp elbows. The rewards for individual performance and the culture of the organization often overwhelmed the power of &.

If you are not experiencing the power of &, what can you do to increase collaboration? Three thoughts:

1. As a leader, you are responsible for maximizing the collaboration of your team. Get feedback on the level of collaboration on your team and figure out ways to increase collaboration. Do this with your team, not for them.

2. If your colleagues at work don’t trigger the power of & for you, consider creating a circle of trusted advisors for yourself. Find wise people with trustworthy motives and different perspectives. Open your thinking and plans to them. Dialogue with your circle of trusted advisors. Talk, listen and learn for your benefit and for theirs. Pay it forward by mentoring others.

3. Sometimes the fault lies within us. I can build healthy relationships through service, reciprocity and active listening. Or I can undermine my relationships with self-serving behaviors, a desire to take without giving and talking too much. To get the power of &, I need to do more than my part. If the people around me reciprocate by doing more than their part, we are on the way to powerful collaboration.

Create a collaborative environment with your team. Build a circle of trusted advisors. Reciprocate and listen. Go get the power of &, but don’t go alone.