When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Emotional Intelligence is Dumb

Allen Slade

There is a problem with emotional intelligence. “Intelligence” implies an upper limit on competence. Emotional intelligence, at its worst, implies you can’t exceed your native ability.

Intelligence tests were originally designed to place children into limited academic tracks. At Riverside Elementary School, we had four tracks. At the age of 12, I was placed into the lowest track, designed for students who did not have the intellectual ability to go to college. I decided to prove the school wrong. For every question by the teacher, I was the first to raise my hand. I worked for perfection on every assignment. I helped other students master the material. Because of my efforts, I earned the nickname of “The Professor”. Something fundamentally changed in me during that year. I went to college and stayed for a while. At the age of 28, I was called professor again. But this time it was by my management students at the University of Delaware.

Tracking students based on intelligence tests may or may not be a good education strategy. Limiting your leadership based on “emotional intelligence” is just plain dumb.

What is smarter than emotional intelligence? I prefer to talk about managing emotions. Management – of organizations, projects or emotions – can be learned and mastered. Our emotional competence is virtually unlimited. As a leader, you can get better at understanding and shaping your own emotions. You can get better at understanding the emotional landscape – the patterns and peaks of the people around you. You can master the art of managing emotions.

When life happens, managing emotions consists of four steps:

1. “How am I feeling?” Ask this regularly. Ask this question when you are blocked, when you can’t think straight or when you are shaking. Ask it before the big meeting, before the difficult conversation, before the Big Ask. Ask it when you are surprised by life’s events. If you want to develop your emotional competence, I recommend using an emotional log. Regularly ask “How am I feeling?” and then record their observations. An emotional log helps you master monitoring of your emotions.

2. “How are my emotions serving me right now?” If your emotions are serving you well, continue on.. If your emotions are not serving you well, ask yourself:

3. “Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better?” Are you too intense? Too flat? Are you experiencing fear (flight response) when anger (fight response) would serve you better?

4. “How do I get there?” For more moderate emotions, you can center or take a deep breath. For different emotions or for more intense emotions, you can silently declare your desired future to yourself. Since you are the most credible person you know, you can probably persuade yourself. You can touch an object or totem to remind yourself of your purpose and passion.

Two weeks ago, I was preparing for a radio interview on managing emotions. About 20 minutes before we went on air, I noticed my writing was wobbly and my voice had a slight tremor. I reflexively went through the four steps: 1. How am I feeling? Nervous, excited. 2. How are my emotions serving me right now? I will sound nervous on air, undermining what I hope to communicate. 3. Would different emotions (type or intensity) serve me better? Yes. The type of emotions are appropriate, but they are too intense. I like to have an edge when I speak, but I need moderate intensity. How do I get there? I took five minutes to center before I went on air.

I started the interview in a better emotional state. During the interview, I continued to monitor my emotions. When I felt my emotions ramping up too much, I took a deep breath (after covering my mike). I touched my signet ring to remind me of my purpose and passion. Listening to the recording of the interview, I observed good content, good grammar and clear phrasing but too many fillers (ums and ahs). I was probably still too much on edge. I will do better next time. Interview performance, like emotions, can be mastered.

At Slade & Associates, we create dialogue and insight for intelligent change. Intelligent change often means exceeding preset boundaries. There is no upper limit on your emotional competence. You can learn to manage emotions. Like managing projects, going to college or radio interviews, you just need to work at it.

What to Expect from Executive Coaching

Allen Slade

Promising athletes who want to reach the top almost always have a coach. When they reach the highest level of competition – the Olympics, the NFL, the World Cup, the PGA/LPGA – coaching is even more important.

Coaching is valuable for leaders also. Leadership coaching increases your ability to achieve results, build healthy relationships and stretch into your best self as a leader. Leadership coaching is better than training or mentoring at developing leaders. To get to the top of any field – executive management or professional golf – is hard. To stay on top is even harder. If leadership coaching is good early in your career, then executive coaching is absolutely necessary to stay at the top.

Executive coaching builds on leadership coaching in many ways. Executive coaches help you continue to polish your leadership skills while they help you build skills in strategic thinking and leading from a distance.

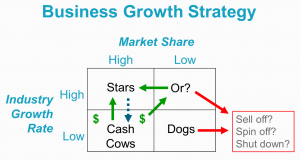

Strategic thinking is the seeing the big picture of organizational success. As an executive, you must be look for dynamic systems and complex interactions. You cannot master only functional strategy. You must have a general management perspective that integrates all functions – operations, marketing, finance and people – to create bottom line success. You must grow the business: competitive strategy to maximize your market positions and corporate strategy to manage your mix of businesses. You may have had a business class with business growth strategy models like this:

I have taught strategy (using diagrams like this). I have also managed strategy. Trust me, strategy is more complicated in practice than in the classroom. An executive coach can be your thinking partner as you stretch into new levels of strategy formulation, implementation and evaluation.

Leading from a distance is the ability to lead with or without substantial personal contact. As an executive, you may have mastered interpersonal leadership, but now you must also be influential with people you hardly know. Leading from a distance requires broadcast communication skills like speeches, all-hands email and other mass communication. With hundreds or thousands of employees, you must also become expert at listening at a distance – getting upward feedback from the managers who work for you, from employee surveys and from town hall meetings. Executives may also need to move beyond interpersonal leadership presence to true charisma. A coach can help you jumpstart your broadcast communication, feedback and charisma.

An executive is a competent leader, and more. An executive coach should be a competent leadership coach, and more. An executive coach should have a proven track record as a leadership coach (including accreditation by the International Coach Federation), real-world strategy experience and facility with large group communication and feedback. Executive coaches should have experience as an executive or C-suite consultant. They may have graduate education in strategy or organizational psychology.

Being at the top can be lonely. Executives stand out from the pack in performance, but they also stand out because they have passed by their peers and almost all potential mentors. As the CEO, you truly have no peers in your organization. Your board has to balance helping you succeed with its fiduciary responsibility to evaluate your performance. An executive coach is a safe partner to discuss your strenghts and weaknesses. Your coach can help you turn your failures and shortcomings into learning opportunities without imposing judgement on you.

Chemistry between you and your executive coach is important. I recommend working with a firm that has a stable of proven executive coaches. Then, if you and your coach do not have the right chemistry, there are other coaches who can step in to give you the help you deserve. At Slade & Associates, we have a range of coaches, including our own associates and executive coaches at Healthy Companies International.

As an executive, you should have experts to help you maximize the financial and operational performance of your organization. You should also have an expert to maximize your own performance. If you need an executive coach, get one. If you have an executive coach already, throw yourself into improving your executive performance. If the chemistry with your executive coach is not right, get the executive coach that fits your needs. Do whatever it takes to get the coaching you need to stay at the top of your game.

What to Expect from Leadership Coaching

Allen Slade

Gifts can be a source of joy or a nasty surprise. If your company provides you a leadership coach, how should you react? Heartfelt delight or muted disappointment? Is leadership coaching the perfect gift for you? Or is it the ugly sweater?

Leadership coaching is a powerful gift when it works as designed. Coaching increases your ability to achieve results and build healthy relationships. It helps you stretch into your best self as a leader.

A talented and wise coach (preferably accredited) will help you stretch into your best self. The coaching conversation can be the high point of your week. Your coach’s insightful listening and powerful questions can trigger new insights into your leadership. The best coaches assume that you are the expert on your own situation. Your coach will draw out your expertise through inquiry, curiosity and gentle challenges. The mini-experiments you design together can lead to breakthroughs in your influence and your presence as a leader.

Leadership coaching comes in different flavors:

Coaching for achievement maximizes your performance in your current role. The leader wants to move from good to great. Your leadership coach will help you focus on the behaviors and thinking necessary to supercharge performance. For achievement coaching to have maximum value, you need to have already learned the ropes. That means 6 months or more in your current job.

Coaching in transition helps you adjust to a new role so you can have a fast start. Your coach will help you learn the ropes – making sense of your new role. Rapid sense-making will help you adjust your behavior, thinking and expectations to accelerate maximum performance in your new role. Transition coaching may start before, during, or soon after the leader has moved into a new role. Sometimes, recruiting firms will provide a leadership coach to ensure that the placement has the greatest odds of success.

Coaching in crisis is designed to turn around an unsuccessful situation. The leader’s performance is unacceptable in one or more ways, and the leader and the organization want to improve the situation. Successful crisis coaching requires the leader, HR and the leader’s manager to agree to have mutual candor, commitment to change and the expectation that things can improve.

When can the gift of coaching turn out to be an ugly sweater? One example is coaching in crisis when the organization has already decided to end the leader’s employment. Another example is when the leader’s confidentiality is violated.

Most ICF accredited coaches take steps to avoid these situations. If no turnaround is possible, Slade & Associates does not offer coaching in crisis. (However, if the leader’s employment is at an end, we gladly offer career coaching as part of outplacement packages.) We always require a written agreement of strict confidentiality. Our approach to leadership coaching safeguards our dialogue, maximizes your insight and drives intelligent change for your organization.

Leadership coaching is an incredible benefit. If your organization offers you a leadership coach, accept the gift gladly. Check on the coach’s credentials. Make sure your coach, your organization and you agree on the purpose of the coaching. Demand coaching confidentiality. Then, prepare to be surprised and delighted as you unwrap the insights and wisdom of leadership coaching.

Many Mini-Experiments

Allen Slade

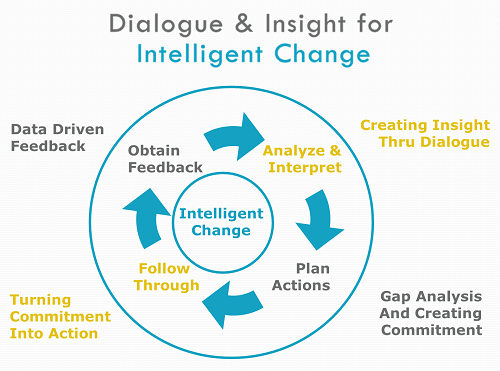

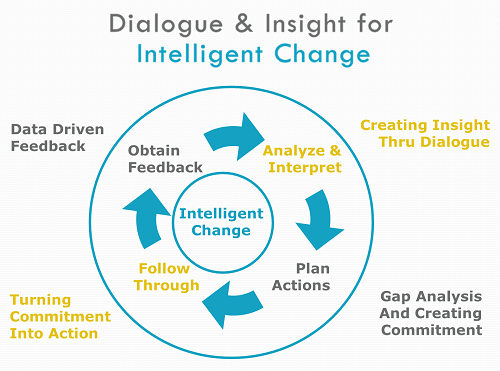

In Teachers, Mentors and Coaches, I made the case for the value of coaching for adults who want to grow as leaders. Teachers impart expertise. Mentors impart experience. Coaches create dialogue and insight for intelligent change. And a big part of what coaches do is to create mini-experiments.

Coaching dialogue is different from normal conversation. At the beginning, a client and I reconnect and check on previous mini-experiments. In the middle, we discuss the issues facing the client. I bring active listening, powerful questions and direct communication to the conversation. I do not bring an agenda. You, the client, set the agenda, because you are the expert in your own situation. If you want to talk about next week’s meeting, the marketing strategy, a difficult customer or the new IT system, I am good with that.

If the first 50 minutes are dialogue and insight, the last ten minutes are action planning. I work with my clients to create mini-experiments at the end of each coaching session. A mini-experiment is an action plan to try something new and different. For an executive, this might be a different approach to growth strategies. For a leader, it might be managing emotions before a speech. For a career coaching client, it could be a simulated interview. Since the client is the expert on the situation, I propose mini-experiments as a SMART request. The mini-experiment is SMART because it is specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. It is a request because the client can respond yes, no, offer to negotiate or decide later. We usually negotiate – the client raises valid concerns, and I ask “What would work?” Together, we create something SMART that can drive intelligent change.

Whether in the physics lab or the conference room, an experiment requires a hypothesis and measures. The hypothesis might be “If I do [something different], then my strategies/speech/interview will be better.” To figure out whether the hypothesis holds water, we need measures that produce data. The best data will compare the old way of doing things with the new way. This data needs to be credible and relevant to you the client, so that you are confident of your evaluation of the different way of doing things. We probably don’t need the rigor of a sophisticated experimental design or statistics. What works for you works for me as your coach.

A leadership coaching client was having difficulty with a key executive. Our coaching conversation hinged on how the executive fell short of expectations. However, my client saw the needs of his customers as an opportunity for creative problem solving and servant leadership. We reached a key insight: customer shortcomings were energizing but executive shortcomings were deflating. We designed a mini-experiment: “Think of your boss as your customer for the next week. See how that impacts your attitude toward your boss.” At our next coaching session, I checked on how the mini-experiment went. My client reported it was hard to think of his boss as a customer. But when he did, he had a more positive attitude, resulting in upward problem solving and service to his boss.

This was not a “bet your career” experiment. It happened to work. If it had not worked, we would have discussed why, and either tried the “boss as customer” idea again with a SMARTer action plan or else come up with a new approach. Because of minimal risk, quick turnaround and limited effort, you can do many mini-experiments.

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

Interview: Managing Emotions and Coaching

Allen Slade with Elaine B. Grieves

This one hour conversation covered how to manage emotions and the positive impact of coaching. The interview appeared on Leader Talk, an internet radio show.

Teachers, Mentors and Coaches

Allen Slade

Who sparks your growth as a leader? Who triggers dramatic turnarounds in your career?

As kids, growth was our job, but someone else set the agenda. Adults, including our parents and teachers, helped us climb the ladder to maturity. As we climbed, we took more responsibility for our own learning. The college professor did not manage our days like the kindergarten teacher. After college, we became even more specialized in skills, more complex in thinking and more diverse in motivation.

So, who has the biggest role in your learning today? A teacher? A mentor? A coach?

Teachers impart knowledge based on their expertise. The best teachers are subject matter experts with strong platform skills. They know the material and they know how to deliver it. Yet, corporate training classes suffer from a lack of transfer of training back to the work situation. Traditional teaching does not impact adults like it impacts 5-year olds. Adults need individualized, experienced-based growth.

Mentors impart wisdom based on their experience. Mentoring can be a powerful experience, sharing personalized knowledge and advice customized to the needs of the mentee or protégé. Yet, mentoring tends to be hit or miss. Most formal mentoring relationships do not make it past the second meeting.

At the extreme, teaching and mentoring requires adult learners to suspend their disbelief in their own expertise and experience. Teaching and mentoring are built on a shaky assumption:

You do not know what you need or how to get it. You need an expert teacher or an experienced mentor to guide your learning.

Our adult mindset resists returning to this child-like belief. “He got schooled” is a taunt rather than an effective training strategy. “Listen to your parents” grates on teenagers, so it is not surprising that mentoring often misfires for adults.

Coaches are different. A coach believes you are the expert in your own situation. Instead of giving you the answer, a coach is more likely to ask questions. Instead of setting goals for you, a coach will help you define your own goals. Instead of holding you accountable, a coach helps you hold yourself accountable.

Coaches give up control to gain influence. As a professor, I required my students to show up at the appointed time and place, ready to discuss the assigned readings. But once the final grades were in, my control ended and my influence largely disappeared. As a coach, my influence is soft but lasting. As a coach, I don’t tell people what to do, how to do it or when it is due. I just ask questions and share distinctions. I request behavioral agreements, but I encourage my client to say no to my requests. I do not enforce the agreements. I merely ask about the impact of not following through. Yet, the impact of coaching can be life-long, resulting in new thinking patterns, more effective habits and changed values, attitudes, beliefs and expectations.

Bottom line: Training and mentoring have limited impact on experienced professionals, leaders and executives. Coaching is more likely to maximize your leadership influence or trigger a career turnaround.

There are situations that call for training or mentoring. Training works well for transfer of knowledge, like learning a new online application. Mentoring is great for new hires. However, for most adults in most situations, coaching is more powerful than either teaching or mentoring.

The difficulty with coaching is cost. In comparison to one-on-one sessions with a certified coach, classroom training is cheap. Mentoring is free.

Cost is important, but not the only consideration, especially when we seek life changing assistance. We don’t typically look for the cheapest medical care. We turn to our company for health insurance. We don’t depend on free legal advice. We budget to pay for an attorney.

If you seek leadership coaching, take advantage of what your company offers. You may have an internal coaching program or a personal development budget.

If you seek career coaching, budget for it. Your return, in increased salary and life satisfaction, will be worth the investment.

Don’t wait for someone else to decide what you need. If you think you would benefit from coaching, you are right. You are right, not because you agree with some expert on coaching. You are right because you are the expert on your own growth.

Feedback Should be “Just Right”

Allen Slade

A careful reading of Goldilocks and the Three Bears suggests three lessons for leaders: Moderation in all things. Don’t be impulsive. Breaking & entering causes problems, especially at the Bears.

Previous posts have looked at The Problem with Feedback and Different Perspectives on Feedback. Today, we will consider moderation in two aspects of feedback. Instead of a single feedback cycle that may be too hot or too cold, just right feedback requires that you mix the timing of your feedback cycles. And, don’t just impulsively act on feedback. Use insight and analysis to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose.

Multiple Feedback Cycles

As a leader, you should be open to feedback because you need to know “When I walk in the room, who shows up for the other people?” You need to seek out feedback relentlessly.

But it is not enough to collect feedback tidbits. To drive intelligent change, you must analyze and interpret the feedback you receive. You must plan actions based on the feedback. You must follow through with your plans. Then, you must start the cycle again by collecting more feedback. If things are going well, continue on. If your feedback suggest things are not going well, change something – your follow through, your action plan or your analysis and interpretation of the feedback. This feedback cycle drives intelligent change.

How long should your cycle take? Consider feedback cycles of three lengths:

Long-cycle feedback. This is feedback on long term impact, such as data from the annual employee opinion survey or a 360 report. Long-cycle feedback looks at the sum of your actions over a period of time. Long-cycle feedback is typically generated by the organization with safeguards to increase its validity (e.g., anonymity) and relevance to organizational leadership (e.g., a competency model). Yet long-cycle feedback by itself is not enough to develop your leadership. The assessments underlying long cycle feedback are complex and open to rating errors. And, a leader cannot afford to wait a year to find out if leadership changes are effective.

Short-cycle feedback. This is feedback on a recent event, such as post action feedback right after a meeting. Short-cycle feedback looks at your actions in the very recent past. The advantage of short-cycle feedback is that it reduces the delay in adjusting a new behavior. The disadvantages of short-cycle feedback are often a lack of anonymity and a lack of structure.

The quick check-in is a useful form of short-cycle feedback. After a conversation or meeting, ask “How did today’s conversation (or meeting) go for you?” Most of the time, the answer will be “It went well.“ or ”Great.” In that case, continue on. Sometimes, you will hear something of incredible value. “We are bogging down in the data.” “To be honest, I was bored.” “You have spinach between your teeth.” Treat this feedback as a valuable nugget. Adjust the agenda, amp up the excitement or do a quick floss job.

Instant feedback. This is feedback in the moment, such as watching non-verbal language of others in a meeting or hearing a change in voice tone during a phone call. Instant feedback allows the leader to adjust on the fly. Instant feedback requires mindfulness of the cues that others give in the moment. It also requires the ability to multi-task by talking and watching, by focusing on your message and your impact on the other party, at the same time.

You need a mixture of these cycles. Instant feedback and short-cycle feedback, in excess, may be too hot. Long-cycle feedback, by itself may be too cold. But, combined in the right proportions, these different cycles can be just right.

Balancing Openness to Feedback with Constancy of Purpose

When you receive feedback, another form of moderation is needed. You need to consider the feedback before acting. In the heat of the moment, while receiving negative feedback, you can go overboard. You can impulsively agree to do everything the feedback giver wants. This strong desire to please can backfire. If you submit totally to the other person’s judgment, you undermine the powerful dialogue that should come with feedback. And, you subordinate your purpose to their goals for you. In effect, you jump from feedback to action plan without your own careful analysis and interpretation.

It is better to balance openness to feedback with constancy of purpose. The other person’s feedback is always valid and always valuable. Yet their goals for you may not be identical to your purpose. My advice is to accept all feedback from all willing parties, without necessarily submitting to their action plans for you. The balanced reaction to feedback is to listen, to learn and to engage the other person in mutual problem solving.

Back at the Bears

Let me close with another observation: Goldilocks had no support team for her decisions. Impulse can be moderated by wise counsel. Mixing feedback cycles is more complex than simply waiting for annual leadership feedback. Balancing openness to feedback with constancy of purpose is harder than a simple rule for action. I recommend using the power of collaboration to maximize the power of feedback. Work with your circle of trusted advisors, your mentor or your leadership coach to master feedback. Gather a support team to create dialogue and insight to drive intelligent change for your leadership.

Bottom line: As a leader, actively seek feedback. Gather the right mix of long-cycle, short-cycle and instant feedback. Balance constancy of purpose with openness to feedback. Gather your support team to get your use of feedback just right.

And don’t break & enter, especially at the Bears.

The Problem with Feedback

Allen Slade

Most of us readily accept praise. But leaders can struggle with accepting and acting on constructive criticism. They can balk at negative feedback. Sometimes, it is reasonable to reject feedback because of its low credibility or irrelevance. However, habitually rejecting feedback suggests a deeper pattern – a world view that sees feedback as a problem.

Let’s get personal. How you respond to negative feedback?

Recall the last time you got substantial negative feedback on your work performance or professional relationships from your manager, colleague or close friend at work. How did you react?

1. I saw the feedback as an attack or threat.

2. I saw the feedback as disapproval or judgment.

3. I defended myself, denied the feedback was valid, or delayed receiving the feedback.

4. I accepted the feedback, even though I wanted to do well.

5. I welcomed the feedback.

6. I invited additional feedback.

Suzanne Cook-Greuter lists seven ways to respond to feedback[1]:

Opportunist. Focuses on own immediate needs and opportunities. Values self-protection. Receives feedback as an attack or threat.

Diplomat. Focuses on socially expected behavior. Values approval of others. Sees feedback as disapproval or judgment.

Expert. Focuses on expertise, procedure and efficiency. Values expertise in self and others, but takes feedback personally as an attack on own expertise. Defends, denies, and delays feedback, especially from lesser experts.

Achiever. Focuses on delivery of results. Values effectiveness, goals and success. Accepts feedback if it helps achieve personal goals and improve effectiveness.

Individualist. Focuses on self interacting with the system. Individual purpose and passion are more important than the system. Welcomes feedback as necessary for self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of their own behavior.

Strategist. Focuses on linking theory and practice. Looks for dynamic systems and complex interactions. Invites feedback for self-actualization.

Magician. Focuses on interplay of awareness, thought, action and effects. Values transforming self and others. Views feedback as natural and essential for learning and change.

Today’s post focuses on opportunists, diplomats and experts – those who have response 1, 2 or 3 to negative feedback. Let’s look at each in more detail:

1. An opportunist lives for the moment, seeking passion with little long-term purpose. Since feedback is painful, the opportunist sees it as an attack or threat.

2. The diplomat wants to get along well with others. Feedback is disruptive. The diplomat prefers smoothing over differences.

3. Experts do not like feedback in their area of expertise, because it undermines their expertise. An expert will grudgingly accept feedback from a superior expert, but they often defend themselves by attacking the other person’s expertise.

Because of their problem with feedback, opportunists, diplomats and experts often struggle as leaders. In my experience, leaders must see themselves through the eyes of those they wish to lead. Cook-Greuter found that over 50% of adults have the mindset of an opportunist, diplomat or expert[2]. If half of us struggle in accepting feedback, is it any wonder that there is a shortage of effective leadership?

Bottom line: If you have a problem with feedback, you will struggle as a leader. Shift from seeing feedback as a problem to seeing feedback as a gift.

I am optimistic that anyone with a passion for leadership can develop the purpose necessary to accept feedback. Anyone who wants to help people can develop the norm that feedback is acceptable. Anyone who wants to be the best leader possible can become an expert in seeking and using feedback.

Changing your view of feedback is not easy. It requires substantial growth and development, possibly even a fundamental shift in your world view. Reflection, coaching and practice may help you open yourself to negative feedback. Reflection, such as a journaling, meditation or quiet time, can help you examine yourself and shape your impact as a leader. Leadership coaching helps you create a plan to improve your feedback skills and hold yourself accountable to put that plan in action. Like any other competence, practice accepting feedback is necessary. You need to find the right situations to practice receiving negative feedback. You may want to start in a safe and supportive environment, such as with your coach or in a training class. Then, practice with your trusted circle of advisors in your work situation. Soon, you will want to practice requesting feedback from a wider circle – including people whose expertise or motives are not always clear. Feedback from the bozos and politicians is a gift, because their perspective impacts your leadership as much or more than your circle of trusted advisors.

The problem with feedback is our unwillingness to receive negative feedback. The solution is simple but difficult: See feedback as a gift. If you solve the problem with feedback, if you tackle this simple but difficult change, you will become a better leader and lead a richer life.

[1] This table is adapted from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004) “Making the case for a developmental perspective,” Industrial and Commercial Training, 36, 275-281.

[2] Data from Suzanne Cook-Greuter (2004), p. 279.

The Leader’s Tipping Point

By Allen Slade

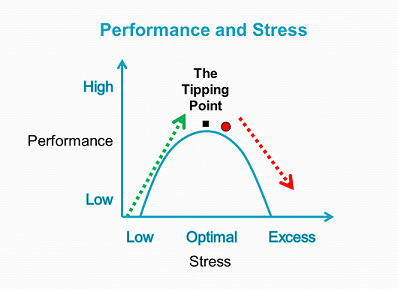

Leadership is about creating sustainable performance in your team. Jim Clawson points out that effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” In a post on The Tipping Point of Performance, I talked about managing energy in others to create sustainable performance. As a leader, you have a proven track record of results. You combine competence, capacity and committent to success, so people are willing to follow you. But is your performance sustainable?

Bottom line: As a leader, you have to manage your own energy. Know your performance curve, watch for signs of an impending performance crisis and take dramatic action as needed.

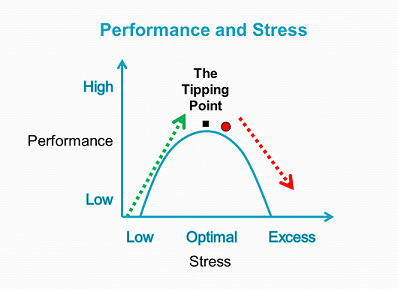

The performance curve is just as true for you as it is for the people you lead. We all experience this inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between your level of stress and your performance holds, but only in the green zone.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

If you are in your own green zone, you adjust your effort level to the demands of the situation. Stress triggers higher performance. If you face higher demands, you stay longer, work harder, decide faster. All is well until you reach your tipping point. Then, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance, from yourself or from external demands, drives you into the red zone. You become the red marble accelerating down the performance curve. As a leader, a stress-induced performance crisis not only hurts your productivity, it can undermine your credibility as a leader.

Bottom line: Push youself, but know your own tipping point. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Manage your own stress wisely, especially on the dangerous part of the performance curve.

Stress reduction strategies. Whether you are at the top of the green zone or at the tipping point, try stress management strategies. Simplify your life. Practice centering. Off load non-essential work. Get help from your boss, in terms of more people, more resources or more time. Ask your colleagues for support. Delegate to your team.

Develop yourself. Long-term, grow your capacity for performance to avoid a stress-induced performance crisis. Develop new skills. Practice skills to the point of mastery. Practice for speed, not just completion. If you can write methodically, practice writing under a deadline. (Blogging three times a week is speeding up my writing!) Coaching can help, whether you are an executive, leader or golfer. At Slade & Associates, we coach executives and leaders to maximize their performance. There are certain things we don’t do, so you would do well to find your own golf coach.

Your urgency in reducing your stress depends on your position on the performance curve:

Top of the green zone. If you push harder but don’t see much improvement, you may be approaching the top of your green zone. Be careful, because you could hit your tipping point. Be alert for further stress, and consider strategies to reduce stressors or increase your performance capacity.

The tipping point. Approaching your tipping zone is dangerous. If familiar tasks become harder, if your inbox is overwhelming, if you snap at reasonable requests or if you work longer with fewer results, you may be at your tipping point. At the tipping point, you still have time. You can think. You can experiment with one stress reducer at a time. Take action now to reduce your stress. Climb back down into the green zone while you can still think clearly.

The red zone. Passing your tipping point is catastrophic because of the accelerating downward spiral of performance. To get out of the red zone, aggressively implement stress management strategies. Make a plan that combines at least two or three big stress reducers – simplify, center, get support from your boss, delegate, etc. Make smart requests ask your boss for support or delegate. Whatever the details, take dramatic action. In the red zone, you must act now.

A lifeguard. I must confess: This red zone advice may not work. The downward spiral of performance undermines your decision making and behavioral flexibility. If you are drowning, sometimes you can’t save yourself. You need a lifeguard who will know you need help and step in during a crisis. Your lifeguard could be a friend, a mentor, a coach or your family. Before a red zone crisis, build strong relationships. Be transparent, accountable and open to constructive feedback. Then, if you are drowning in stress, you will have someone willing to dive in to save you.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for yourself and for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.

The Tipping Point of Performance

Allen Slade

I love sports movies, especially about underdogs. The critical moment is when the coach or loved one gets the underdog fired up. I love Rocky II, when Talia Shire lights Rocky’s fuse from her hospital bed and Remember the Titans, when Denzel Washington gives a moving call for unity in the Gettysburg cemetery.

As a leader, do you try to fire up your team? Be careful. If you play with fire, you can get burned.

Clearly, there are times when you need to establish a sense of urgency. But asking for extraordinary effort can backfire. As the performance curve below shows, there is an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance. A straight line relationship between stress and performance does hold, but only in the green zone.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

A leader who operates in the green zone can increase performance with stress. A complacent team may benefit from getting fired up. Stress triggers higher performance. The leadership situation has to be right: sufficient trust, basic equity and the capability to perform better. Given those things, adding some stress adds some performance. More stress creates more performance. This straight line relationship is a simple recipe for success: up the quota, accelerate the deadline, give the locker room speech or crack the whip and the underdog becomes the champ.

The problem hits at the top of the curve. When a person reaches the tipping point, more stress equals less performance. Further pressure for performance leads to a downward spiral in the red zone. People become anxious. They act indecisively, work slower or make more mistakes. As their performance decreases, their anxiety increases, further decreasing their performance. Notice the red marble at the top of the performance curve. In the red zone, the marble accelerates down the curve of poor performance. As a leader, if you push a person too far, their performance drops. And, their performance will continue to get worse because of the downward spiral.

Bottom line: Push for performance, but avoid the tipping point for stress. As Bob Rosen says, lead with just enough anxiety.

Aim for high performance, not peak performance. I coach leaders to avoid pushing people to their tipping point. If the tipping point is at 100% performance, aim for 90 or 95%. Then, your team member has a stress buffer. If there is a coffee spill that wipes critical data or a car wreck going to the big meeting, they will have the psychological reserves to get through it. If you push to get the full 100%, your people may tip into the red zone.

Develop your people. If you wish to increase performance, but a person is near the tipping point, think development first, motivation later. Increase their competence and capacity, so they can perform better while maintaining an essential stress buffer.

Be a lifeguard. Your people can drown in stress. The downward spiral of performance undermines decision making and behavioral flexibility. If someone is in the red zone, you may need be their lifeguard. Watch for signs of stress in your team members, watching for people at the tipping point or in the red zone. Then, throw them a life line. Offer more resources, renegotiate deadlines, offer them time off to refresh and rest. Be creative – think of the rousing speech that fires up the underdog, then do the opposite.

Know your team. Everyone is different. The people you lead have different capabilities and stress tolerances. They will show different warning signs of a stress-induced performance crisis. Get to know your people before a crisis. Have regular dialogue with every team member. Seek insight about their performance patterns, personal stressors and individual signs of overload. This will equip you to be a stress lifeguard.

Being mindful of the performance curve can help maximize sustainable performance for the people you lead. So go lead with just enough anxiety.