When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

You’re Not Listening

Active listening is a key skill for leaders. In a previous post on Two Steps to Active Listening, I defined active listening as “the art of listening with intensity to truly hear what the other person says, knows and feels.” Leaders who actively listen are more effective, more persuasive and more engaging than leaders who don’t actively listen. It is good to know what active listening is. It is also good to know what active listening is not. Let’s look at other ways to listen.

Carol Wilson¹ lays out five levels of listening:

2. Sharing

3. Advising

4. Attentive Listening

5. Active Listening

The first three levels don’t contain the word “listening” for good reason: When you’re interrupting, sharing or advising, you’re not listening.

Levels 4 and 5 are truly listening, and we will talk about them in a later post. Today, let’s look at levels 1, 2 and 3.

1. Interrupting

“That really didn’t go well. I am worried about . . .”

“Did you see the game last night? The officiating was awful.”

When you interrupt, you build yourself up at the other person’s expense. In effect, you are saying “Be quiet because what I have to say is more important.”

How often do you interrupt others? Maybe you are rushed, anxious or annoyed. Maybe the other person has raised a topic you want to avoid. Whatever the reason, you drain energy by stepping on their airtime. A little patience, a bit of deference and a dose of etiquette will make you a better listener and a better leader.

2. Sharing

“My boss always takes credit for my work. It’s just not fair.”

“Yeah, he did the same thing to me. I made this killer presentation, but he just put his name on it and presented to the vice-president.”

With sharing, when someone shares their experience, then you share a similar experience. You may think you are reinforcing their experience, but you are really minimizing their unique situation. When the other person is speaking, you are focused on preparing your response. In other words, you are silent but not listening too hard.

When you appear to be listening, are you just waiting your turn? Do you value your experiences more than the experiences of the other person? Serve the other person by focusing on their story – your story can wait.

3. Advising

“I get really nervous when I present to the Design Group. Sometimes I shake like a leaf.”

“Try practicing in front of a mirror.”

As an accomplished professional, you have experience, expertise and insight. When someone presents you with a problem, it is easy to shift into problem solving mode.

As a problem solver, listening is critical to help you diagnose the situation so you can provide the best solution. However, it is tempting to listen only enough to figure out the problem. If your default listening mode is advising, then listening can come across as a necessary evil rather than a worthy pursuit.

Problem solving is a good thing. The problem with problem solving is we use it too much and we use it too soon. We present solutions when the other person needs dialogue. We jump to solutions instead of deep-diving issues, understanding values and exploring causality.

If someone presents you with a problem, do you quickly offer a solution? Do you listen just enough to be confident in your solution? Listen more – it will lead to better solutions. Listen longer – the other person may solve their own problem. Listen better – it will show you care.

You’re Not Listening

Interrupting, sharing and advising have two common roots. The first root may be your self-confidence. You value your own experiences, insights and problem solving capability. However, your self-confidence may bulldoze the other person’s need to be heard.

The second root may be your lack of confidence in the other person. Their conversation may show immaturity. Their wisdom seems lacking. They, after all, have come to you. If you lack confidence in them, it logically follows that you will talk more so they will talk less.

Whether you suffer from too much self-confidence or too little confidence in the other person, the end result will be too little listening on your part and too much interrupting, sharing or problem solving.

Listening Starts With Humility

The best listeners are humble. They value the other person highly. They have patience because they know the other person has important things to say. The best listeners serve by having more questions than answers. And, they would rather help the other person solve their own problems.

Notice how you listen. Notice when you shift to interrupting, sharing or problem solving. If your interruption, your story or your solution does not serve the other person, then I will give you Bob Newhart’s classic advice: stop it.

Instead, take the two steps to active listening: be quiet and value the other person. You may find the resulting dialogue leads to better insight, better solutions and a better relationship.

______________________

¹Carol Wilson, “Tools of the Trade” Training Journal, July, 2010, pp. 65-66.

Two Steps to Active Listening

Listening skills are critical for leaders. Listening opens the channels for two way communication. And it is not enough to simply be present when others are talking. You must engage in active listening, the art of listening with intensity to truly hear what the other person says, knows and feels.

I have coached b-school students, change management clients and leadership coaching clients on how to listen better. Based on those experiences, here are two steps for active listening.

1. Be Quiet

The first step to active listening is simple. Stop talking. Let the other person speak without interruption or comment from you. Surprisingly, this step is often the hardest, especially for people who are smart, driven and successful.

Sometimes we act as if silence implies consent. When someone says something wrong or they focus on unimportant aspects of the issue, we want to jump in to set things right. But you can hear without necessarily agreeing. Like a reporter interviewing politicians or a researcher gathering consumer opinions, you might not agree with what is being said, but you can stifle your impulse to speak in order to truly understand the other person’s point of view.

There is another reason to be quiet. Silence is power. In most social situations, we expect talking to fill every moment. Your silence implies personal control. Being silent means you are confident and comfortable. If you can be quiet, the other person may feel compelled to fill the uncomfortable silence.

2. Focus on the Other Party

The point of active listening is to get the other person’s perspective. To do that, you must focus on them – completely.

Use reflective listening. Repeat and paraphrase what you hear. Use phrases like “I hear you saying…” or “It sounds like…” Ask questions of clarification like “Why do you think that happened?” “When did she first say something?” or “How did that work out?” Summarize their key points. When they have given you lots of facts and reasons, try to draw out the themes. And be tentative, always checking with them to see if you understand what they are trying to say.

But it is not enough to listen to the other person’s words. You must also watch their non-verbal communication. Watch facial expressions, tone of voice and body language. Check your observations by using the phrase “You seem to feel . . .” It is especially important to notice when their words and their non-verbal communication seem to be at odds. For example, if the other person tells you they fully support a certain decision (while their eyes are downcast, their voice has no energy and their posture is slumped), follow up to see if there are some unspoken concerns.

A Difficult Conversation

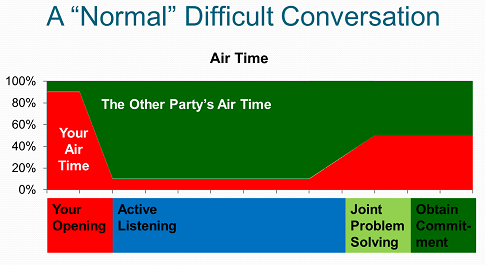

Suppose you need to have a difficult conversation with someone. You may need to discuss a broken commitment, call out unacceptable behavior or give feedback on poor performance. While you might think talking more increases your chance of persuading them, you might be surprised by the power of active listening. The best difficult conversations follow this pattern:

Active listening is central to this difficult conversation. By being quiet and focusing on the other party, you are helping move them toward joint problem solving and commitment. Your active listening helps them process the difficult topic. You are gaining credibility by listening. And, you will actually learn their perspective, which may change your mind about the situation and the other person.

Active listening is central to this difficult conversation. By being quiet and focusing on the other party, you are helping move them toward joint problem solving and commitment. Your active listening helps them process the difficult topic. You are gaining credibility by listening. And, you will actually learn their perspective, which may change your mind about the situation and the other person.

Difficult conversations require wisdom. Active listening is a great way to be wise. “Whoever restrains his words has knowledge, and he who has a cool spirit is a man of understanding.”¹

If you are like me, you sometimes struggle with difficult conversations. Active listening is a great way to fake wisdom. “Even a fool who keeps silent is considered wise; when he closes his lips, he is deemed intelligent.”²

A Gift

Many people live in a cone of silence. They go through most days without being heard, without being really listened to. As a leader, you can give a few minutes of your time by actively listening to the people you lead. The benefits to them and to your organization will be worth your time.

__________________________

¹Proverbs 17:27

²Proverbs 17:28

What’s Your Best Alternative to Negotiating?

In a failed attempt to lean in, W., an anonymous woman with a Ph.D. in philosophy, asked to negotiate better terms of employment at Nazareth College. Unfortunately, she had her job offer unilaterally rescinded. Many bloggers have commented on why this happened, ranging from gender bias by the college to narcissism and cognitive errors by the candidate.

Here’s another way to look at the situation: The job market is ripe with people who have a Ph.D. in philosophy. Nazareth College probably had a backlog of candidates with similar credentials. Passing over W. was an easy decision. In other words, the college had a BATNA – a “best alternative to a negotiated agreement“.

Negotiating With a BATNA

Negotiation is a dance of offers and counteroffers. With a BATNA, you can choose to sit out the dance. You have acceptable options, so you are not forced to reach a agreement with this employer, job candidate, supplier or customer. You can negotiate from a position of strength.

The employer’s perspective. As a hiring manager at Ford Motor Company, whenever I posted an opening, I would receive a stack of resumes. After the HR department pre-qualified the candidates, I might have 100 resumes left. I would quickly discard most of the resumes, then carefully review 10 or 15 resumes before calling a handful of worthy of candidates. I never negotiated starting salary or benefits. If a candidate asked to negotiate, I would have gone to the next person on my list. My BATNA was a large, diverse and desirable pool of candidates, so there was no reason to negotiate.

The job candidate’s perspective. It is best to interview when you already have a job. Then, your BATNA is to stay where you are. If you don’t have a job, try to generate multiple job offers that overlap. When I decided to move back home to Virginia, I still had a tenured faculty position at my previous college. I interviewed aggressively and received four separate job offers. I always kept one job offer “live” until I received a better offer. I eventually accepted an offer at a prestigious college 30 miles from where I grew up.

Negotiating Without a BATNA

If you really have no BATNA, you have no bargaining power. If you must have that blue 1968 Shelby GT 500 on the auction block, expect to pay top dollar. If there is only one acceptable job candidate, expect to pay top salary. If you are desperate for a job, expect to take whatever they offer.

Here is how to negotiate without a BATNA: Act confident, like you have a BATNA. And the best way to be confident is to find your hidden BATNA.

The employer’s perspective. As a hiring manager at Microsoft, I was looking for someone special – big data expertise, specific programming languages, HR business partner perspective and a willingness to live in the drizzle of Redmond. I opened a hiring requisition, but no acceptable candidates were found. Despite having the requisition open for months, I never even interviewed anyone. I preferred to leave the job unfilled (my hidden BATNA) than to hire someone without the full set of skills I needed. I was confident in my own capacity and the flexibility of my team to succeed, even if we had an empty box on the org chart.

Employers always have the BATNA of leaving a position open. A bad hire leads to poor performance and can create a drag on the rest of your team. You never “have” to hire anyone.

The job candidate’s perspective. As a job candidate, you always have alternatives – hidden BATNAs. I have been known to say “I would rather live in a refrigerator box than do that job.” For graduating students, the alternative to a professional job might be working for minimum wage or going to graduate school.

Whether or not the refrigerator box/Starbucks/grad school is a realistic alternative, confidently acting like you have a BATNA makes you more attractive. I once had a job interview over lunch. While glancing at the menu, the hiring manager started listing his expectations for my work schedule. I told him the schedule was a deal breaker. He insisted that all jobs in our field would have a similar schedule. I confidently disagreed, then selected my entrée. I enjoyed our lunch. Within a month, I interviewed elsewhere (with confidence) and got the job I wanted.

Why did W. go public in her failed negotiations with Nazareth College? In the firestorm after the original post, W. said “I asked for a less then 20% increase in salary [at Nazareth College]. When I negotiated for another tenure track offer in philosophy I asked for a more than 20% increase in salary and was offered it [emphasis mine].” If the other offer was still on the table when she negotiated with Nazareth College, she had a BATNA – as every job candidate and hiring manager should.

Know your BATNA or find a hidden BATNA to give yourself more negotiation power. And, if you truly don’t have a BATNA, smile and say, “Why yes! Thank you!” to your only choice.

The Indirect Cost of Growing Leaders

My wife and I have cultivated a square foot garden for many years. The work is enjoyable, the produce is delicious, and we save a bit of money. Every spring, we refresh the soil and purchase flowers, tomatoes and broccoli plants.

For organizations, growing leaders internally is like gardening. You invest time, energy and money upfront. In return, you get better leaders than you can purchase at the recruiter’s grocery store.

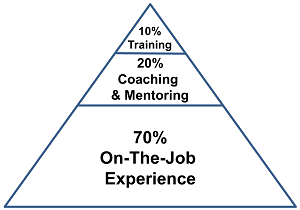

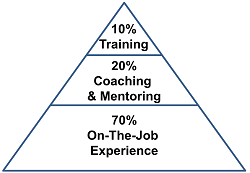

Leadership development, done well, consists of three components:

Training, often in a formal classroom setting, Formal training should be a small proportion of your  development process because of cost and poor transfer to the work situation.

development process because of cost and poor transfer to the work situation.

Coaching and mentoring help transfer classroom training to the job. They also target the specific growth needs of the leader. Coaching, especially, has the greatest potential to maximize leadership influence or trigger a career turnaround.

On-the-job experience is where most leadership growth happens. For leaders to grow, however, leadership experience must be staged well.

Direct Costs and Indirect Costs

Formal training has a direct cost. Coaching, if done with certified, external coaches also has a direct cost. Mentoring and on-the-job-experience have little or no direct costs.

With classroom leadership development, the direct costs are a small piece of the overall costs. In my experience, the indirect costs are much greater. Suppose you have a one-week training class for high potential individual contributors and first level managers. Their performance should be worth at least twice their pay, benefits and overhead (office space, computers, etc.). If your leaders have average compensation (salary, bonus, stock) of $100,000/year, we can assume their benefits would be about $50,000, and their overhead might be $25,000 . One week of leadership development for 20 leaders costs almost $135,000 in lost productivity.

On-the-job experience may seem cheaper, but once again the indirect costs are huge. If you develop leaders through job rotation, the performance valley of the transition can cost the organization at least six weeks of performance. If you rotate those same 20 leaders to new jobs, expect indirect costs of lost performance to exceed $800,000.

Leadership coaching is surprisingly affordable when you consider indirect costs. Many coaching engagements consist of an hourly coaching session once a month, usually at the leader’s office. The leader will typically invest another hour on follow-up work, trying out new behaviors in mini-experiments). As I coach, I often ask the leader’s team to give feedback on the leader. If the leader has a team of 12 who each invest 20 minutes in feedback, there is a loss of about 4 hours of productivity. For a year of coaching, the indirect costs for the group of 20 leaders would be less than $100,000 – cheaper than either a week of training or an annual job rotation.

Bottom line: Leadership development is costly. The indirect costs of lost performance is larger than the direct costs, and leadership coaching has less indirect costs than classroom training or job rotations.

“Let’s Cut Costs by Cutting Leadership Development”

It can be tempting to cut out leadership development when times are tough. However, growing leaders only when times are good is shorted sighted. You will not develop as many leaders, and you will develop leaders who prosper in good times but may falter in tough times.

When I started Slade & Associates as a full time venture, we had to manage our cash flow. So, we spent more money on the garden. We added a square. I also built a light box to grow plants from seeds to reduce purchases at the local nursery. In our first year, the garden yielded more than the costs of the space and the light box. And since then, we have enjoyed the extra yield and lower costs every planting season.

We use our light box in late winter and early spring to extend our growing season. I recommend that organizations do the same by growing leaders during economic winter. Cutting back on leadership development during an economic downturn is burning your leadership capital to improve your cash flow. It is penny-wise and pound-foolish. If you grow leaders during the winter, your organization will be positioned for even more success when the weather turns.

Help Leaders Keep Their Bearings with Hot Ethics Training

Allen Slade

When I was a midshipman with the U.S. Navy, it was post-sail but pre-GPS. In the middle of a training exercise, our captain turned off the LORAN system. He wanted to make sure his officers could figure out their location and destination even if the satellites failed.

The U.S. military also relies on its leaders to have a strong moral compass. Yet, despite a focus on preventing sexual assaults, the number of reported cases has increased.

One strategy to maintain ethical bearings is through targeted training. Yet training does not always work. Two recent instances of alleged sexual misconduct involved a sergeant who was a Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention coordinator and a colonel in a sexual-assault prevention office. The sergeant and the colonel surely had gone to almost every sexual ethics training class without the desired impact.

Ethics training can be effective, but only if you address the root cause of the ethical lapse. In Why Leaders Fail, I suggested three types of ethical lapses (based on the research of Mary Gentile):

Failures of Awareness – not knowing what kinds of ethical breaches might occur.

Failures of Analysis – being aware of a sensitive issue but not knowing how to think through the ethical situations.

Failures of Action – being aware of the issue and able to analyze the situation, but not acting according to your values.

Most training focuses on transfer of knowledge or skills. But ethical lapses rarely come from lack of awareness or faulty analysis. Instead, most leaders fail at the point of action. They notice the issue, they know what to do, but they don’t act or they take the wrong action.

Cold Training for Hot Action?

Classroom lectures are emotionally cool. PowerPoints and videos do not provide much emotional heat. Case studies, group discussion and exercises can be a bit warmer, but if the classroom environment is “safe” then the emotional warmth is fleeting and inauthentic.

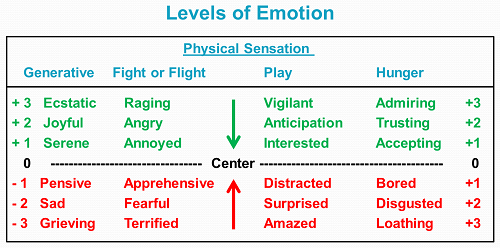

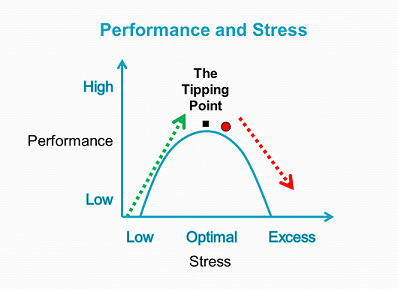

Ethical lapses occur in emotionally heated situations. As our emotions heat up, our cognition narrows. Our decisions are faster but our choices are fewer. Fear or anger triggers our “fight or flight” reflex. Creativity lessens and we struggle to balance competing priorities. Cold training does not prepare us for hot action.

Hot Training

You can increase the emotional temperature of leadership ethics training through simulations. But not just any simulation will do. Simple decision making simulations, such as the Army’s “Team-Bound” video game, can be too simple and emotionally uninvolving to help with ethics training.

A powerful simulation engages the intellect and the emotions. You need meaningful stakes to add heat – the training has to count. And the simulation must have subtlety and time pressure.

For example, I worked with a hiring simulation for recruits for a B-to-B sales job. The recruits prepared for a meeting with a simulated buyer. The “buyers” quickly put the recruits in their place. They interrupted, complained about the recruits’ inexperience, and refused to listen to reason. To win a job offer, a recruit had to be emotionally hardy AND persuasive.

Another example is the S&A simulation “Cleaning Up the Clunkers.” It has complex decisions, time pressures and temptations to make it emotionally realistic. The participants buy scrap cars and resell the recyclable content. While most participants don’t see Clunkers as an ethics simulation, there are opportunities to short change customers, breach contracts and illegally dispose of toxic wastes.

Hot training – meaningful stakes, subtlety, complexity and time pressure to engage the intellect and the emotions – is much more likely to shape how leaders decide to do the right thing in the heat of the moment.

Training is Only Part of the Answer

Leadership training should only be part of your leadership development process. I like the 10%/20%/70% rule of leadership development:

Most of your efforts should go into on-the-job development, with coaching and mentoring available to bridge the gap between the classroom and the job. Coaches and mentors should be fully versed in your organization’s ethical standards and have a deep understanding of ethics in action.

Bottom line: Cold ethics training does not help leaders take the right action in the heat of the moment. To prepare leaders to make the right choices, you need hot training that simulates the time pressures, complexities and emotions at the point of action. And you need coaching and mentoring to connect training to on-the-job experience.

At Slade & Associates, we are passionate about helping leaders create dialogue and insight for intelligent change. We don’t offer cold ethics training because it doesn’t create change. Maybe you shouldn’t either.

Why Leaders Fail

Allen Slade

Leaders face tough decisions, with competing priorities, time pressures and poor data. When their decisions blow up, the debris field of failure can hurt their career, their team, their organization and their customers.

Why do leaders fail? Mary Gentile categorizes ethical lapses into three categories:

Failures of Awareness – not knowing what kinds of ethical breaches might occur.

Failures of Analysis – being aware of a sensitive issue but not knowing how to think through the ethical situations.

Failures of Action – being aware of the issue and able to analyze the situation, but not acting according to your values.

Think of a leader who failed you or your organization. Did their failure spring from lack of awareness or faulty ethical analysis? I suspect not. In my experience, most leaders fail at the point of action. They notice the issue, they know what to do, but they don’t act.

As a leader, how can you increase your odds of taking the best action?

As a professor, I would love to say that education in ethics is the answer. Yet, after decades of business ethics classes, our leaders don’t seem any more ethical.

I remember one CEO who told me that while interviewing a recent MBA graduate for a job, he asked the man whether he had taken a course in business ethics. When the interviewee answered yes, the CEO asked him what he had learned. The job candidate explained that he had learned about all the models of ethical analysis – deontology, virtue ethics, consequentialism, and so on – and that whenever he encountered a conflict, he could decide what he wanted to do and then select the model of ethical reasoning that would best support his choice. Needless to say, this was probably not the intended lesson of the class.

Mary GentileEthics classes, whether in college or in businesses, can help with ethical awareness and analysis. However, if we are aware and analytical enough going in, ethics classes won’t help at the point of action. Facing a professor in an air conditioned classroom is not the same as facing a union rep in a hot, noisy plant or arguing with your vice president when your job is on the line.

As a leader, you need to be able to manage energy in yourself and others to face ethical challenges. You must be able to manage your emotions in the midst of a storm. And you must also be able to hold difficult conversations to address ethical issues with others.

Finally, you need courage. Courage is not lack of fear. Courage is doing the right thing in the face of fear. It helps to grasp the things of this world lightly in order to hold firmly to your convictions.

In my first week at Microsoft, a vice president, my boss and I discussed “what would happen if” we were asked to violate employee confidentiality. I said, if asked to violate confidentiality, I would quit. After a brief pause, I said “No, that’s not true. I won’t quit. I will call our vendor first, tell him to erase all our data, then quit.” The meeting quickly broke up, my boss high-tailed it down the hall and I was left standing outside the VP’s office. I called my wife at home to let her know we might not need to unpack the moving boxes.

The VP apologized the next morning, and I was never asked to compromise confidentiality.

My unplanned outburst cemented the confidentiality of our employees. And, it happened in part because I was willing to let go of my job to hold onto my convictions.

Bottom line: Ethical failure usually springs from inaction at the point of crisis. As a leader, you can triumph in tough situations if you manage your emotions, master difficult conversations and, most importantly, have the courage to act.

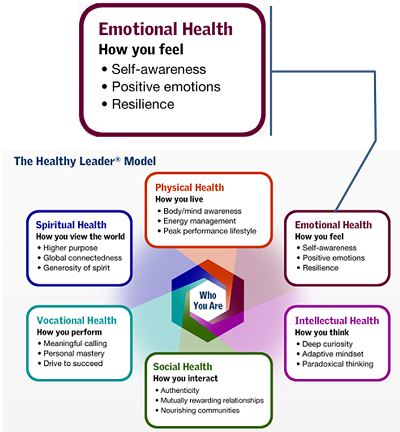

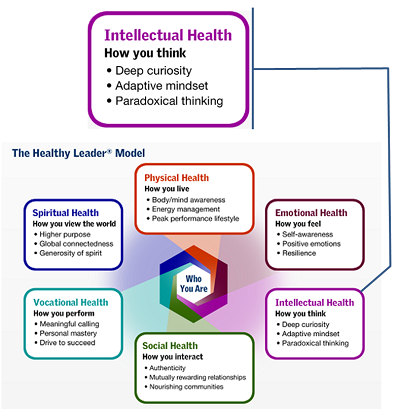

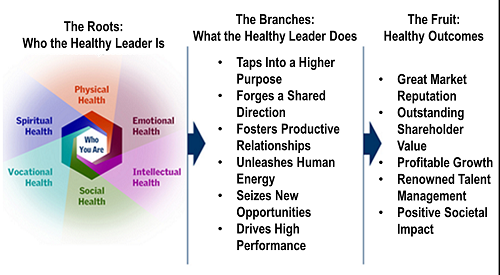

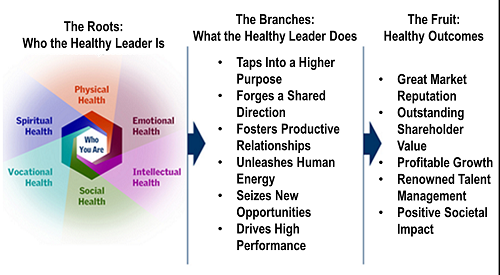

Images of Healthy Leadership

Allen Slade

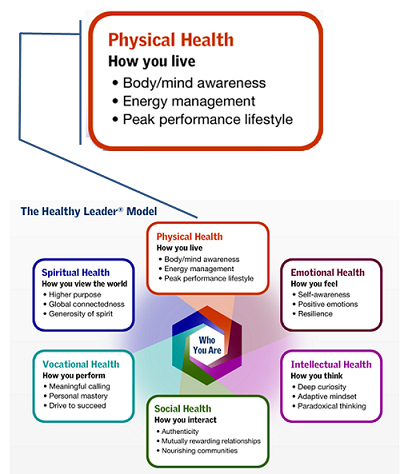

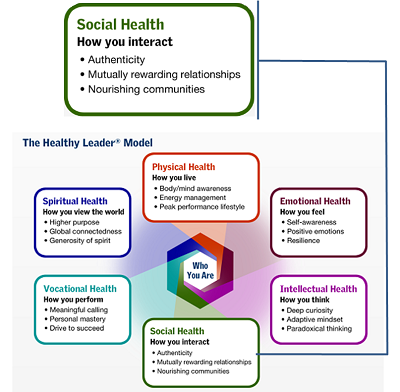

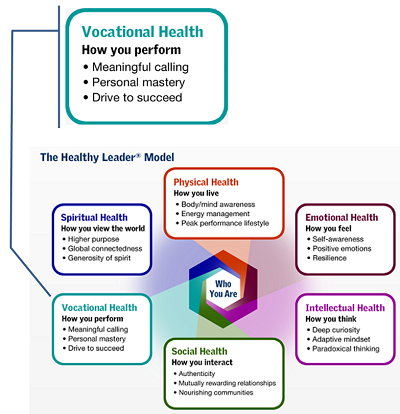

To wrap up my series of posts on the Healthy Leader® model by Bob Rosen of Healthy Companies International, I invite you to enjoy these images of healthy leadership.

The Roots of Healthy Leadership

Image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

The Six Aspects of Leadership Health

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

The Branches of Healthy Leadership

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

The Branches of Healthy Leadership

Allen Slade

I like to think of leadership as a tree. For the tree to bear fruit, you need healthy roots and healthy branches.

The roots of leadership are who you are as a leader. Unhealthy roots will stunt the branches and diminish the fruit. In my series of posts on The Healthy Leader® model (from Bob Rosen of Healthy Companies International), we have considered six roots of healthy leadership:

- The leader’s physical health

- The leader’s emotional health

- The leader’s intellectual health

- The leader’s social health

- The leader’s vocational health

- The leader’s spiritual health

Today, let’s look at six branches of healthy leadership – the effective leadership behavior that generates positive outcomes for the organization.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Tap into a Higher Purpose

Healthy leaders awaken passion in others. They help their team unite around a common purpose and focus on shared values. They help others have intense pride for the organization.

Forge a Shared Direction

Healthy leaders forge a shared direction with inspiring goals that are owned by the team. They communicate a clear roadmap for success. They align efforts through ownership of broader organizational goals

Foster Productive Relationships

Healthy leaders create productive work relationships for themselves. Healthy leaders model authenticity and generosity. They welcome diversity and competing points of view. They also create an open and productive work environment to help others create productive relationships.

Unleash Human Energy

Healthy leaders are the spark plug that ignites the energy of others. They appreciate individuals. They encourage others to contribute their best self every day, and they recognize their individual contributions. They help map out clear paths for future growth, then they provide challenging roles and stimulating learning opportunities.

Seize New Opportunities

Healthy leaders focus on value creation. They help their team leverage assets to reach goals. They help their team anticipate market moves and capitalize on growth opportunities. And they help their team recover quickly from mistakes.

Drive High Performance

Healthy leaders focus on meeting commitments. They help their team do whatever it takes to consistently get the job done. They empower people to succeed, they measure what matters and they reward success.

Bottom line: If your leadership is a tree, how healthy are the branches? Would your team say that you engage in these healthy leadership behaviors? If not, you may need to enrich your leadership: Tap into a higher purpose. Forge a shared direction. Foster productive relationships. Unleash human energy. Seize new opportunities. Drive high performance.

But be wise. Your behavior flows from who you are. If the branches are not healthy, you may need to look to the roots of healthy leadership first.

What’s your next step? If you are a leader or executive, Slade & Associates can help assess the health of your leadership. We can also provide executive coaching and leadership coaching for individuals who want to enhance who you are and what you do.

If you are a senior executive or a leadership development professional, we can help assess leadership across your organization. Then, working as your partner, we can create customized leadership development programs and coaching systems to make a difference for your leaders.

Whatever your situation, strive for healthy roots and branches to make your leadership fruitful.

The Leader’s Spiritual Health

Allen Slade

When leaders face unpleasant tasks or difficult demands, they must tap into a reservoir of motivation. Their motivation can be internal or external, but if the reservoir is dry, leaders will not be motivated to do what must be done.

Early in my career, my manager would respond to complaints about workload by saying “That’s why they pay us the big bucks.” He was trying to motivate us through the external reservoir of rewards. Since we were paid less than average, his words were not especially motivational.

Yet, my group was quite motivated. We were creative and diligent, we worked long hours without overtime and we changed the company for the better. It was because of our internal reservoir of motivation – our higher purpose, our global connectedness and our generosity of spirit. We discussed our plans in light of the bigger picture. We gave without expecting a return. In other words, our spiritual health kept us going in the face of difficulty.

In my series of posts on The Healthy Leader® model (from Bob Rosen of Healthy Companies International), we have considered the leader’s physical, emotional, intellectual, social and vocational health. Today, let’s look at the leader’s spiritual health.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Spiritual health is your ability to tap into a sense of connection with something bigger than yourself and to feel compassion and empathy for others. Spiritual health drives social responsibility and helps us see opportunity in the midst of adversity.

Spiritual health may flow from religious beliefs, but spiritual health is not the same as religion. There are religious believers who are motivated by rewards and punishments, which is not spiritually health. There are people who are not especially religious who have a higher purpose, global connectedness and generosity of spirit. Let’s take a deeper look at the leader’s spiritual health.

Higher Purpose

Do you ever ask yourself “Why am I here?” The spiritually healthy leader has a good answer, because they can see the higher purpose of what they are doing. They work to improve the lives of others. They see the legacy they are building at work. They enjoy fulfilling their organization’s higher purpose and they get a charge out of making a difference in the world.

Knowing why you are here also helps you engage others in your organization. When I became Director of Microsoft People Research, the organization was known for doing an annual employee survey. I helped create a higher purpose for our group and I engaged senior leaders to help contribute to Microsoft’s positive impact on the world. I still have the fleece vest.

Global Connectedness

As the vest says, “Do great research. Create insight. Change Microsoft. Change the World.” Spiritual health goes beyond improving your own work or even your own organization. You strive to improve the world. You see every decision as having the potential to make things better for all. Your vision includes people with different traditions, cultures and religions. You look for the best ideas from around the world and you strive to improve things locally and globally in all of your work.

Generosity of Spirit

Spiritually healthy leaders pay it forward. They do good without expecting to receive something in return. They are optimistic, generous, empathetic and compassionate. They are a role-model for sharing and giving back.

Bottom line: Your spiritual health as a leader flows from your higher purpose, global connectedness and generosity of spirit. By tapping into something bigger than yourself, you will keep your internal reservoir of motivation full for the frustrations you face. You will also be a role model for the people you lead.

The Leader’s Vocational Health

Allen Slade

Decades ago, I heard an old-line manager say “Managers manage and workers work. Never get the two confused.” He saw work as something beneath his pay grade. I suspect his employees felt like cogs in a machine. If so, they probably did the minimum necessary to avoid being “managed”.

The reality is that your vocational health is foundational to your leadership. You lead by example. Your career joy is infectious. Your personal mastery and your drive to succeed set the standard for the people you lead. If you think of work as drudgery, if you don’t control your work self or if you do just enough to get by, your leadership will falter as you pull people down to your level.

In my series of posts on The Healthy Leader® model (from Bob Rosen of Healthy Companies International), we have considered the leader’s physical, emotional, intellectual and social health. Today, let’s look at the leader’s vocational health.

Modified from an image courtesy of Healthy Companies Inc.

Meaningful Calling

Does work energize you or drag you down? Our energy at work is determined in part by our sense of calling. When work is a meaningful calling, it becomes a source of joy and energy for us. When we use our talents fully in our work every day, we are more alive. With my career coaching clients, I talk about calling as the intersection of your ability, your affinity and your career opportunities. When you are in the sweet spot of your career, your abilities are applied to tasks you enjoy, and your contributions make a difference for the organization. If you are not in your sweet spot, you may need to change your job or change your thinking.

When you are in the sweet spot of your career, your abilities are applied to tasks you enjoy, and your contributions make a difference for the organization. If you are not in your sweet spot, you may need to change your job or change your thinking.

Harsh reality can cause us to work outside our sweet spot. We may enjoy something and be quite good at it, but the need for a living wage may force us to do something else. However, over the long run, it is better to adjust your life style downward to take a job in your sweet spot. When I moved from being a professor at the University of Delaware to an entry level HR job at Ford Motor Company, I took a pay cut. When I moved from Microsoft back to being a professor, I took an even larger pay cut. Yet, both times, I moved into jobs in my career sweet spot.

If your work is not a meaningful calling but you cannot change jobs, don’t be a Debbie Downer. Your vocational health may benefit from a change in thinking. If you expect work to be boring, unchallenging and meaningless, it probably will be. On the other hand, if you come to work with a sense of expectation, you will often find meaning. If you look for what is good, true, beautiful and effective, you will usually find it.

Personal Mastery

Jim Clawson says effective leadership is “managing energy, first in yourself, then in those around you.” Your vocational health rises or falls depending on your desire for self improvement. You need to have a clear view of your strengths and weaknesses and a clear path on how you will improve.

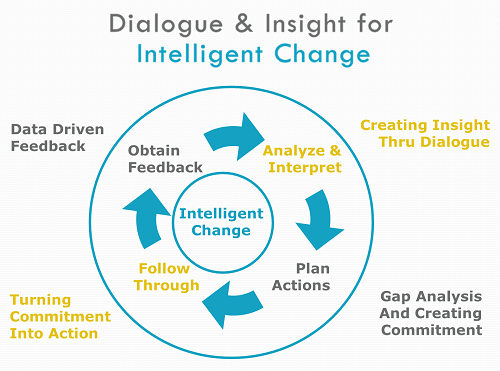

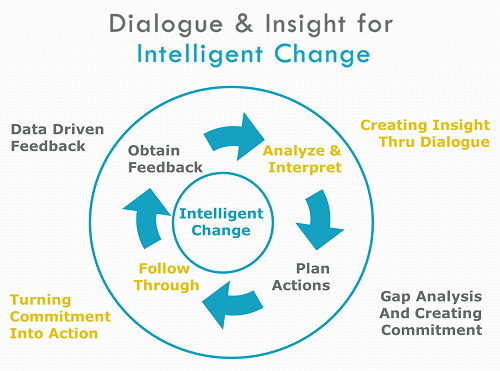

At Slade & Associates, we help our clients pursue intelligent change through dialogue and insight.

Intelligent change starts with feedback that is fleshed out through dialogue. As the leader sees gaps, he or she makes a commitment to try something new – what we call a mini-experiment. After following through with action, the leader gets more feedback and contains the virtuous cycle of growth.

Personal mastery takes openness to feedback, commitment to change and personal insight. These things may or may not be in your habitual approach to work. A leadership coach can help you increase your personal mastery and your vocational health.

Drive to Succeed

Your ability to accomplish goals and outperform your peers is essential for your vocational health. Drive to succeed starts with visualizing success, often as a stretch goal. Then, you have an urgent push to accomplish what you have visualized.

Most managers want people with a high drive to succeed. They do not want people who fear failure so much that they avoid difficult tasks or clear goals.

Drive to succeed is related to the personality construct of need for achievement. My research with Mike Rush shows that people high in need for achievement lean in to difficult tasks. If you are blessed with high drive to succeed, you will have a greater level of vocational health.

People who are low in achievement motivation are high in fear of failure. While they do not avoid more difficult tasks totally, they prefer easier tasks or tasks with no clear measure of success. They may avoid jobs with hard and fast goals (like sales). They may avoid getting the degree they need because of test anxiety, an especially potent effect of fear of failure.

Suppose you experience fear of failure? Are you stuck with low achievement motivation and lesser vocational health? Not at all. Personality is not destiny. You can make choices to succeed, and overtime, those choices will become habits that reshape who you are. I have seen coaching clients overcome fear of failure and become more goal driven. I have helped students overcome test anxiety to graduate with honors and go on to graduate studies. It is a matter of choice, with a bit of coaching or mentoring support.

Bottom line: Your vocational health as a leader is built on meaningful calling, personal mastery and drive to succeed. Through career choices and coaching, you can increase your vocational health so that your leadership flourishes.