When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Change Intelligence Quotient

Given that 70% of large scale changes fail, we need to slant the odds in favor of success. We need better leadership for change.

So, what makes someone good at leading change? Articulating the vision for the change? Connecting with people in the trenches of change? Technical skills, such as project management or design? And, the answer is . . .

[drum roll]

. . . Yes!

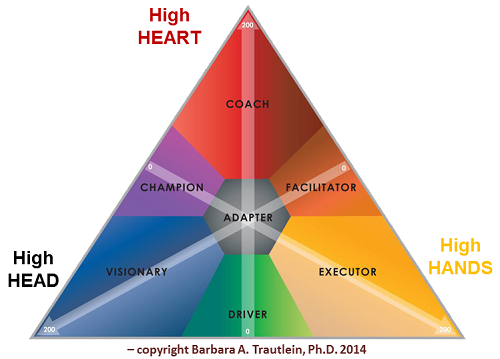

Barbara Trautlein’s research on Change Intelligence: Using the Power of CQ to Lead Change that Sticks suggests three key dimensions to leading change: head, hands and heart.

Head-oriented leaders focus on the long term vision. They are strategic and purpose-oriented, adept at inspiring others toward the bright new future.

Heart-oriented leaders help engage and care for others in the midst of change. They are motivational and supportive coaches.

Hands-oriented leaders make the change happen on time, to budget and to specifications. They plan the work and then work the plan.

Some change leaders are laser focused on just one of the three – head, heart or hands. Other leaders blend two of the perspectives. And, adapters have a balance of head, heart and hands. Taking all the possibilities, there are seven styles of change intelligence.

So, which style is best? Like many things in life, leadership and organizational effectiveness, the answer depends on the situation.

Sometimes a coach engages the heart, but needs a driver to get stuff done.

A visionary may trigger the change while a facilitator is needed to bring people and tasks to the successful end point.

An executor can manage the project details but may need a champion to create the vision and provide the heart to engage people in the long term vision.

And, do not think the adapter is somehow the perfect blend. My style is adapter, leaning toward driver. While my flexibility is valuable in many change environments, sometimes I confuse people by seeming mercurial.

In other words, all seven styles have advantages and drawbacks. What matters is knowing yourself and others, then combining styles and adjusting to the situation to maximize the odds of success for your change efforts. Trautlein calls ability CQ:

CQ (or Change Intelligence) is the awareness of one’s own Change Leader Style, and the ability to adapt one’s style to be optimally effective in leading change across a variety of people and situations.I am on record saying that emotional intelligence is dumb. Why would I write about change intelligence?

Emotional intelligence (or EQ) implies an ability. There is a high and a low, and the high is obviously better. The problem I see is the implication that EQ imposes some upper limit on a leaders emotional capabilities. I prefer to talk about managing emotions, since that is something all leaders can master.

CQ is built on the appreciation of three change leadership focal points – head, heart and hands. There is no judgment implied that one is superior. All three focal points are essential. All seven styles are valuable.

Over the next few weeks, I will be blogging about each of the seven CQ styles – the good things as well as the pitfalls and pratfalls that each style can pose for change leaders. My intent is to use change intelligence to help you know yourself better and to know the other people facing change.

Bottom line: Know yourself, know the people around you and know what challenges you face in a change project. That trick, that knowledge, is a powerful step toward dialogue and insight for intelligent change.

Practicing Leadership Skills in Safety

Leaders trying out new skills can pose problems to their organization. Sometimes the new skills work perfectly from the start. Sometimes these skills create problems for the people around the leader. So how can leaders master the skills they need with minimum risk of collateral damage?

My fifteen year old son has his learner’s permit. To new drivers, this permit represents a bright future full of freedom. But this new freedom requires mastering five thousand pounds of steel and gasoline hurtling through traffic. On my learner’s permit, I rear-ended a parked Buick and slammed it into a Cadillac. Just like leaders in business, new drivers must master new skills with minimum risk of collateral damage.

Our teenage drivers start in a parking lot. The parking lot is a safe place to practice steering and stopping before going on the road. After a few sessions circling the lot, I up the stakes by adding orange cones and paper cups. I challenge my new driver to miss the cones and crush the cups.

The driver accelerates to 15 miles per hour and then attempts to crush a specific cup. They get immediate feedback from the crushing sound and the view in the review mirror. They also get positive reinforcement – praise for a job done well. And, with the orange cones absorbing the punishment of right side errors, the public remains safe.

Leaders should master skills as safely as possible. A well designed leadership development program creates a safe place to practice skills. There should be immediate feedback and lots of praise for success. Failure should impact orange cones instead of actual careers.

I recently created a leadership program to help leaders manage emotions. For realistic practice, the leaders had to experience extreme emotions – fear, vigilance, exhilaration – that can hijack a leader who is driving change, challenging an unethical decision or giving a presentation.

Obviously, we would not create these emotions by putting people’s careers at risk. Instead, we had participants do a high ropes course. They climbed trees, jumped into space and took a zipline across a lake. Real emotions, but in a safe environment. Practice managing those emotions, but nothing worse than freezing up while climbing or declining to jump.

How did it turn out? Every participant mastered the zipline. Almost every participant reported fear, exhilaration or other intense emotions. And many successfully used the skills taught in the classroom to manage their emotions.

The next Sunday, I took my son out driving in the parking lot. He crushed his cups too.

And no collateral damage was recorded, on the zipline or in the parking lot.

Bottom line: As a leader, take appropriate risks. Develop new skills by practicing in safety first.

Before the big presentation, practice with a video camera first, then debrief the video with a leadership coach.

Before a difficult conversation, work with your coach to get the details right.

Before a job interview, practice your stories with your circle of trusted advisors.

Practice until you crush the cups and miss the cones. And, you won’t rear-end any Buicks.

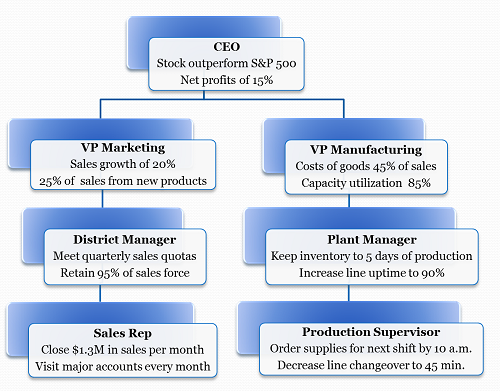

Images of Goals and Metrics

From my blog posts on goal setting for leaders.

.

.

.

.

Management by Objectives? Or Leading with Goals?

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Spoiling Good Goals with Bad Metrics

.

Spoiling Good Goals with Bad Metrics

The Veteran’s Health Administration exists to give the best possible medical care to America’s military veterans. One way to do this is to set goals for standards of care. But the VHA’s good goals were spoiled with bad metrics. According to the Washington Post:

The agency has made it a goal to schedule appointments for veterans seeking medical care within 30 days. But the interim IG report found that in the 226-case sample, the average wait for a veteran seeking a first appointment was 115 days, a period officials allegedly tried to hide by placing veterans on “secret lists” until an appointment could be found in the appropriate time frame.

“We are finding that inappropriate scheduling practices are a systemic problem nationwide,” the report stated. “We have identified multiple types of scheduling practices not in compliance with VHA [Veterans Health Administration] policy.”

The goal to schedule timely appointments was important to the VHA’s mission. It was specific, measurable and time-bound. Yet, the behavior it triggered was not better healthcare for veterans. Instead, multiple leaders and employees at multiple VHA sites cheated the system by distorting the metrics. Why? And, what can leaders do to avoid making a similar mess of their good goals?

A Recipe for Goals

Goals done right can elevate the performance of your team. Recently, I proposed a recipe for leaders to make goals more effective:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Part of being realistic is making sure none of your employees have too many goals.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Create goal-specific metrics to further shape and refine behavior.

Avoid goal blindness. Goals can focus attention and energy too much, causing people to miss other important issues. Use principled leadership, shift your focus periodically and resource goals properly to avoid goal-induced blindness.

If your take steps to avoid goal blindness, and you help your team create goals that are SMART, coordinated and backed by metrics, what could go wrong?

Missing Ingredients Spoil the Dish

Forgetting the yeast will waste a batch of bread, and skipping the sugar will ruin a pitcher of lemonade. The VHA scheduling goal seems to have been missing a few ingredients. The goal was specific, measurable and time-bound, but was it actionable and realistic?

For a goal to be actionable and realistic, those accountable for the goal must expect to succeed if they take the right action. The demand for VHA services has increased with the influx of new veterans and the aging of Vietnam era veterans. In many cases, demand for services has exceeded capacity. There just aren’t enough doctors, nurses, therapists and facilities to care for the patients.

If you set impossible goals, expect failure. The failure may show up right away in the form of missed goals and demotivated employees. Or the failure may be hidden for a while by gaming the metrics. But the failure is inevitable if the goals are not actionable and realistic.

Avoid the Mess

What could can leaders do to avoid making a mess with metrics?

Trust but verify. Metrics must be valid and reliable. Leaders should be trusting, but they should also audit metrics to make sure they are working.

Get experts to review your metrics. Verify metrics with other data, such as checking quality data with customer surveys. Be especially vigilant if people provide their own metrics.

Get experts to review your metrics. Verify metrics with other data, such as checking quality data with customer surveys. Be especially vigilant if people provide their own metrics.

Treat missed goals as a signal. It is tempting for leaders to blame poor performance on their followers. Yet, when goals are missed, they can signal a system failure.

If an employee misses a goal, don’t just reprimand, threaten or punish. Instead, trigger intelligent change. Talk about the causes of performance and help create an action plan to make a difference.

If an employee misses a goal, don’t just reprimand, threaten or punish. Instead, trigger intelligent change. Talk about the causes of performance and help create an action plan to make a difference.

Don’t assume all the actions will be by your employees. As the leader, you may have to create a more realistic goal or provide the resources to make success possible. To fix the VHA mess, Congress should demand action by the Veterans Administration. They should also fund the employees and facilities needed for success.

Bottom Line: As a leader, your job is not done when you set goals with your team. You have to provide resources to your employees so the goals are actionable and realistic. You have to make sure the metrics are valid and reliable. And, you have to respond to missed goals with dialogue and insight. Otherwise, your metrics can make a mess of good goals.

Dedicated to Joseph W. Slade, Sr. and Dallas Wiggins U.S. Army Veterans Patients of the Hampton VA Hospital All veterans deserve the level of care these soldiers received.

Good Goals Gone Bad

Goals are powerful leadership tools that focus attention and effort. Good goals go bad when their power blinds us to critical information or strategic changes.

Good Goals

As a leader, goal setting is an essential part of your leadership toolbox. Like any tool, you have to use goals right:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Part of being realistic is making sure none of your employees have too many goals.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Create goal-specific metrics to further shape and refine behavior.

If your goals are SMART, coordinated and backed by metrics, you will have a powerful leadership tool.

With great power comes great responsibility, for Spiderman and for leaders. The very power of goal setting can create problems. In my post on Got a Goal? Get A Metric! I used a photo of my power saws to illustrate the idea of goals as powerful tools.

My gloved hand is reaching for my zip saw in this picture. I love my zip saw – it is fun, powerful and fast. I also loved those gloves. Loved, because I no longer have those gloves. A day or so after David Slade took this picture, I got careless and touched the moving blade with my gloved hand. I was not injured, but the finger tip of one of my gloves was destroyed. Goals are like my zip saw – powerful, effective and potentially dangerous.

Goals Gone Bad

Here are two example of goals gone bad:

Counting Basketball Passes. Watch this video carefully and attempt to follow the directions. Done? Spoiler alert: If you haven’t watched the video yet, please do so. Most people are so focused on the goal of counting basketball passes that the gorilla goes unnoticed.

In an organization, people can get so busy meeting their goals that they miss the gorilla. A sales person gets focused on meeting their quota, and customer service goes south. A plant manager focuses intently on production and cost goals, and maintenance slips. A general manager focuses on the profit goal and doesn’t notice that employees are burning out. The gorilla – poor customer service, delayed maintenance or employee burnout – can destroy the organization, but leaders do not even notice the gorilla in the room because of their laser-like focus on meeting their goals.

Climbing Mount Everest. On May 11, 1996, a number of people were attempting to fulfill their goal of climbing Mount Everest. Climbers were intensely focused on reaching the summit. When the climbers faced delays on the ascent, they ignored declining oxygen supplies and a gathering storm to push through to meet their goal. Eight people died that day on Mount Everest. Jon Krakauer blamed a number of factors for the deaths, but one powerful factor was destructive goal pursuit. Individual climbers had planned and trained for years. Deciding to turn back would have meant giving up that cherished goal. The expedition companies competed with one another for clients. They also had an intense commitment to the goal of having clients summit Everest.

Relentless pursuit of business goals can lead to death. Auto companies pursuing low costs produce unsafe cars such as the Corvair, Pinto and Explorer. Construction companies taking short cuts on safety practices to meet project deadlines. Truckers fall asleep at the wheel attempting to make just-in-time delivery goals.

In most organizations, no one dies from relentless pursuit of goals. Instead, goal focus creates short term success and long term loss. The goals are met, but the organization alienates customers, employees or vendors.

Avoiding Goal Blindness

In both the basketball video and the fatal Everest climb, the power of the goal blinded participants to vital information. If goals are powerful, their power must be moderated. In other words, leaders are responsible for using goals wisely. Here are a couple of thoughts on how to limit the destructive power of goals:

Lead with principled moderation. As a leader, you need to be a rock in the storm. You have to take a principled stand. In my post on the leadership paradox of principled moderation, I suggest integrity and appropriate transparency as two non-negotiable leadership principles.

Take a look around. An antidote to the focusing power of goals is to shift your focus. Take your eyes off the goal at hand and look to the horizon. Encourage your people to do the same. Pause. Take a breath. Ask powerful questions: “Are we doing the right thing? How does this impact our customers? Employees? Community? Five years from now, will this still seem like a good idea?”

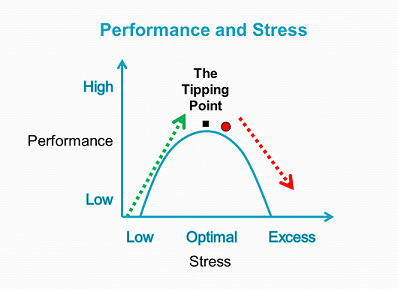

Resource properly. When people are tight on time, energy, supplies or people, they have to push harder to accomplish their goals. Pushing harder makes goal blindness more likely. The basketball video tricks most first time viewers because you have to really focus to get the count right. The Everest climbers had limited endurance and bottled oxygen to make the climb in a narrow window of time. A little more time, a few more supplies or an extra person can help you and your team avoid the tipping point of performance and avoid goal blindness.

Bottom line: Goals are powerful. Use them wisely and take precautions to avoid goal blindness. Then, you can keep your good goals from going bad.

Got a Goal? Get A Metric!

Goals are powerful leadership tools to focus attention and effort. But goals are incomplete without a measure of success.

Basics of Goal Setting

As a leader, goal setting is an essential part of your leadership toolbox. Like any tool, you have to use goals right:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound. Part of being realistic is making sure none of your employees have too many goals.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Give goal-specific feedback to further shape and refine behavior. In today’s post, let’s discuss how metrics work with goals to energize behavior.

A SMART Goal Needs a Metric

A metric puts a ruler on your goal. It provides a number or a category (yes/no) on the behavior or outcome defined by the goal. If your goal is specific, measurable and time-bound, then a metric should naturally follow.

But a metric is not just some “logical” aspect of a SMART goal. A metric provides a motivational complement to a goal. A goal should focus attention and effort to drive performance. The metric shows whether the performance meets expectations. If all is well – the metric shows the goal is being accomplished – then the person should continue their efforts.

If the metric shows all is not well – the goal is not being accomplished – then the person needs to change something. Maybe they need more effort – working harder. Maybe they need different effort – working smarter. Maybe they need better support from you as their leader – better equipment, a bigger budget, just-in-time training, better performance coaching, or whatever.

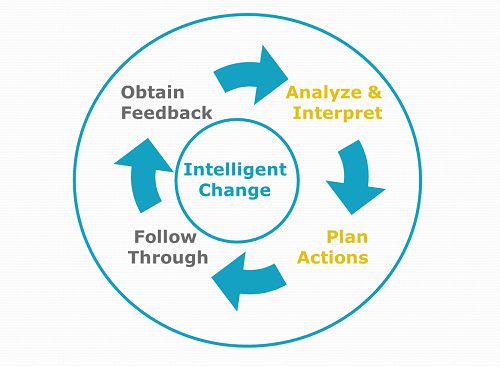

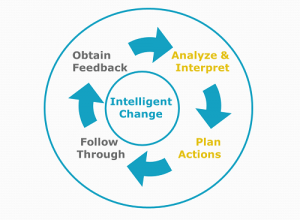

Missing a goal should trigger a cycle of intelligent change:

The initial feedback (unmet goal) . . .

should lead the employee and the leader to analyze and interpret the causes . . .

plan actions to improve performance to the goal and . . .

then follow through with the actions to improve performance.

If the change is simple and easy, one turn of the wheel may be enough. A sales person contacts more prospects and meets their sales quota. Or an operations manager schedules smaller and more frequent deliveries of stock to reduce inventory carrying costs. The simple and easy change drives improved performance, the goal is met, and all is well.

Many times, the change will not be easy and simple. For example, a general manager may miss their profitability goal or a brand manager may miss a market share goal. If the needed changes are complex or difficult, the planned actions may need to be many mini-experiments:

Mini-experiments are planned actions driven by feedback, dialogue and insight. When the mini-experiment is completed, we have another round of feedback, dialogue and insight. And another mini-experiment. The beauty of many mini-experiments is something is bound to make a difference. That’s why we call it intelligent change.

It all starts with a SMART goal supported by the right metric. If a goal provides the power – the effort and attention to drive performance – then a metric provides the measurement to guide the continued application of the power.

In my workshop, I have a number of tools. I am especially fond of power saws. I was coached to “Measure twice. Cut once.” In other words, have your ruler in place before applying the power of the saw.

Bottom line: A metric is a tool of leadership that provides a motivational complement to a goal. Just like you should not use a saw without a ruler, you should not set a goal without a metric.

Too Many Goals?

Goals are powerful leadership tools. They focus attention and effort on the key accomplishments needed for organizational success. If goals are good, are more goals better? As a leader, how many goals should you set?

Basics of Goal Setting

As a leader, goal setting is an essential part of your leadership toolbox. Like any tool, you have to use goals right:

Set SMART goals. Smart goals are specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound.

Coordinate goals. Use management by objectives to ensure goals are coordinated between people and organizations.

Provide metrics. Give goal-specific feedback to further shape and refine behavior. I will discuss metrics more in my next post.

No Goals are No Good

Leadership is managing energy in yourself first and then in others. Goals help you manage energy. Goals provide a destination for efforts. They give direction and quantity for work related behaviors. If you have no goals, your own efforts will be unfocused. And if you do not set goals with your team, their efforts may be unfocused also, or their efforts may be focused on things that do not contribute to the organization’s success.

Too Many Goals

Goal setting is good, but be careful. Too many goals can backfire. The key benefit of a goal is to focus energy. More goals create more focal points. Like a busy instrument panel, too many goals can confuse and distract rather than focus attention.

So, how many goals is too many?

More than three goals is the same as no goals. When a client asks how many goals to set, I use this simple rule of thumb as a starting point.

A simple rule of thumb is better than nothing, but principles of leadership are outdated. Here are more refined ways to think about the maximum number of goals.

More goals with experience. An experienced pilot shouldn’t have trouble making sense of a plane’s control panel. An employee with years of good performance can handle more than three goals.

More goals with phased timing. If you have a complex project, a project plan might have dozens or hundreds of task goals. So long as your employee understands the project plan, the number of goals will not be an issue.

More situational goals. Some goals are relevant only in certain situations. For a retail business, you might have a SMART goal about customer wait times. If customers are not waiting, that goal is not triggered. You can have other goals about stocking or cleaning that are triggered in other situations.

In other words, the maximum number of effective goals depends on the situation your employee faces. To really know how many goals, you should have an ongoing dialogue about goals with your employees.

Goal setting. At the beginning of the performance cycle, set goals participatively. Get your employee’s sense of what is realistic.

Goal performance. While the goals are in place, keep the conversation going. Get to know their work pace and their motivations. Adjust goals as needed, whether it is the type of goal, the level or the number of goals.

Goal review. At the end of the performance cycle, evaluate performance against goals. And also evaluate the goals themselves. Ask how the goals helped or hindered performance. And be open to correcting your missteps in setting goals or supporting your employee’s performance.

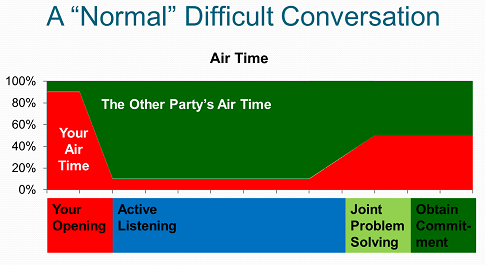

Throughout the goal cycle, keep the conversation going. And, make it a dialogue. Actively listen as much as you speak.

Bottom line: Know how many goals is too many. Understand the situation each employee faces and work with them to set a realistic number of goals. And, if you have created too many goals for an employee, back off. Prioritize and consolidate goals to get the right number of goals. You will help your employees focus their attention and increase their performance.

Images of Active Listening

From my series of blog posts on active listening for leaders.

.

.

Listening in the Performance Valley

Listening in the Performance Valley

.

Energy for Active Listening

Leaders who listen well are more effective, more persuasive and more engaging than leaders who don’t listen. Carol Wilson¹ lays out five levels of listening:

1. Interrupting

2. Sharing

3. Advising

4. Attentive Listening

5. Active Listening

We have thought about Levels 1-4 in previous posts.

- You’re not listening if you’re interrupting, sharing or advising (Levels 1, 2 or 3).

- Attentive listening (Level 4) can be effective, especially in the midst of change.

Today, let’s complete the set by looking at active listening (Level 5) in more detail.

5. Active Listening

“I had the worst meeting with my boss today.”

“What happened?”

“She tore apart my financial report. I was embarrassed in front of everyone.”

“That must have been difficult.”

“You don’t know the half of it.”

“Has this happened before?”

. . .

“Why do you think she reacts that way?”

. . .

“Have you thought about what you can do?”

Active listening takes your leadership to the next level. Like attentive listening, you are focused on the other person and what they say. But you are adding more breadth and depth to the conversation. I define active listening as “the art of listening with intensity to truly hear what the other person says, knows and feels.”

The conversation about the meeting disaster gets to the heart of the issue. The other person’s feelings are validated with the reflective statement “That must have been difficult.” Causality is explored with the “Why?” question. And the other person’s problem solving is activated by asking “What can you do?”

Just the Facts?

Both attentive listening and active listening are powerful and effective tools for a leader. Both focus on the other person and help them make sense of their situation.

So what’s the difference? For me, attentive listening focuses primarily on the facts of the situation. An attentive listener asks “Who? What? Where? When?” Active listening goes beyond the facts to get to reactions and feelings. Active listening consciously explores causal factors and engages the problem solving capabilities of the other person. An active listener asks “Why? How? What’s next?”

Attentive listening focuses on the words of the other person. The active listener goes beyond just the words to notice tone, facial expression and body language. Carol Wilson describes active listening as “listening behind the words and between the words; listening to the silences; using your intuition; promoting the coachee to explore; facilitating the coachee’s self learning and awareness; making suggestions.”

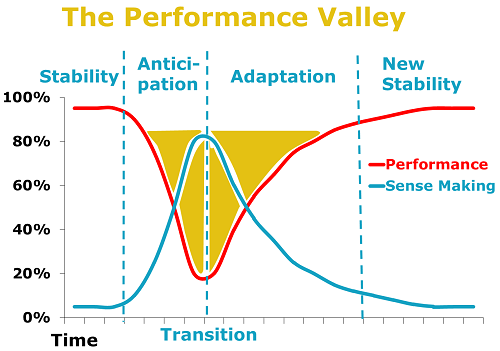

If attentive listening can help shrink a performance valley, active listening is even better. When you actively listen, you have a greater opportunity to address feelings, explore causes and get the other person to solve their own problems. Then, you maximize their sense-making in the midst of change and help them get back to peak performance sooner.

Managing Your Energy

Active listening is powerful and effective. That power comes from your intensity and focus. But expending that level of power can drain your battery.

Bottom line: Active listening is hard. In a classroom exercise, I ask my students to actively listen for seven minutes. Maybe one student in thirty can actively listen for seven minutes.

Don’t be discouraged if you have trouble staying in active listening mode. Like most leadership skills, you can improve your capacity for active listening with practice. If you’re new to active listening, start small. Try this mini-experiment:

- Find someone who needs to talk. Then listen as intensely as possible for ten minutes. Notice how much time you spend in interrupting, sharing, advising, attentive listening and active listening.

- Repeat with another 10 minute listening session. Try to increase your time in active listening. It’s ok to dip into attentive listening, but minimize your interrupting, sharing and advising. Again, notice how much time you spend in each listening level.

- Keep looking for listening opportunities, gradually increasing your proportion of active listening. Then, plan to listen for 15 minutes.

With enough practice, you can achieve 50-70% active listening for an hour.

If you’re already competent at active listening, I encourage you to listen more and better. Increase your active listening capacity like a miler training for a marathon. My mini-experiment in active listening has been going for years. After every coaching session, I still do a self-evaluation of my listening. I am getting better, but I still have a way to go.

Novice or expert, practice will build your listening capacity. And, if you listen carefully, you may notice a few performance valleys shrinking.

______________________

¹Carol Wilson, “Tools of the Trade” Training Journal, July, 2010, pp. 65-66.

Listening in the Performance Valley

Listening is a key skill for leaders. Leaders who listen well are more effective, more persuasive and more engaging than leaders who don’t listen.

Listening is especially useful when the other person is trying to make sense of change. Anticipating and adapting to change requires substantial cognitive effort – what I call sense-making. Sense-making creates a performance valley during change.

A leader who effectively listens can accelerate the other person’s sense-making. That gets them out of the performance valley quicker.

Listening requires you to be quiet and focus on the other person. Carol Wilson¹ lays out five levels of listening:

1. Interrupting

2. Sharing

3. Advising

4. Attentive Listening

5. Active Listening

For levels 1,2 and 3, you’re not listening if you’re interrupting, sharing or advising. Attentive listening and active listening are both ways to truly listen. Today, let’s look at Level 4 – attentive listening.

4. Attentive Listening

“I had the worst meeting with my boss today.”

“What happened?”

“She tore apart my financial report. I was embarrassed in front of everyone.”

“Who else was there?”

. . .

“What did your boss say about the report?”

With attentive listening, you focus on the other person and what they say. You notice their words and ask on-target questions. You help the other person pull their thoughts together. As Karl Weick says “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?” Attentive listening keeps them talking, helping them to know what they think with more breadth and clarity.

So, how can you listen attentively?

- Focus on the facts of the situation. An attentive listener asks “Who? What? Where? When?”

- Pause. Attentive listening requires you to focus on the words of the other person. Go slow enough to truly listen. Don’t plan your next question while the other person is talking. Listen to what they say, then compose your question.

- Allow the other person to pause also. If they are silent after you ask a question, be patient and allow them to think.

With attentive practice, you can become a powerful listener. And, if you listen carefully, you may notice a few performance valleys shrinking.

______________________

¹Carol Wilson, “Tools of the Trade” Training Journal, July, 2010, pp. 65-66.