When you walk in the room, who shows up for Read more →

Holding a Difficult Conversation

Posted Thursday, October 4, 2012Allen Slade

You are gearing up for that difficult conversation. It may be about a broken commitment, setting a boundary to halt abusive behavior or feedback that is unexpected and unwanted. You want to navigate the emotional minefield to minimize the chance of a catastrophic explosion.

Now what? How do you plan the difficult conversation for maximum gain and minimum risk?

Start with the end. In a previous post, I recommended planning your difficult conversation by starting with the end. Have a clear definition of success. Be sure the potential reward of the difficult conversation is worth the cost.

Don’t procrastinate. Bad news is like bread. It is best fresh. After a few weeks you don’t want it in the house. If you need to have a difficult conversation, do it sooner rather than later. If you need time to think and plan or if you want to check your plan with a coach or mentor, fine. But think of waiting hours or days, not weeks or months.

Begin well. Plan your opening statement. Make it appropriately assertive, following this pattern: When you [specific behavior, attitude or thinking pattern], it makes me [specific negative outcome.] Here are some examples:

“When you roll your eyes while we talk, I feel disrespected.”

“When we discuss customer complaints, you tend to blame other employees. This makes me think you don’t see a need for change.”

Listen more and talk less. Be curious about the other person’s reaction. Look to discover why they act/feel/think like they do. Don’t argue. Don’t project an attitude of certainty. Practice active listening by reflecting back what they say and asking lots of clarifying questions.

Anticipate their reaction. At a basic level, put yourself in their shoes. If you were on the receiving end of this difficult conversation how would you react? Even better, figure out the other person’s general pattern of responding to feedback. Do they have a problem with feedback or are they generally open to feedback? Then, prepare for their reaction. Control your emotions, listen without agreeing and keep the conversation moving ahead to address the issues.

Seek mutual problem solving and commitment. The goal of a difficult conversation should be intelligent change. To change, you need to work with the other person, first to figure out how to change and then to get a commitment to change. You should aim for a smart request, a specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time-bound proposal that the other person accepts.

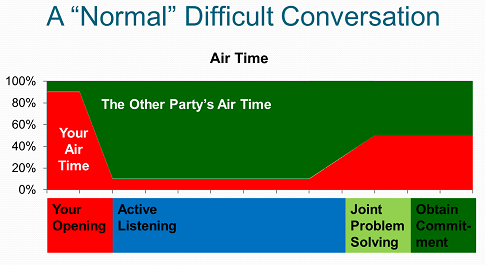

When you are at your best as a leader, your difficult conversation should follow this pattern.

You will give most of the airtime to the other person. Only during your brief opening will you do most of the talking. The longest part of the conversation is your active listening, where you may do 10% of the talking or less. When you get to joint problem solving and mutual commitment, you should look to do 50% or less of the talking.

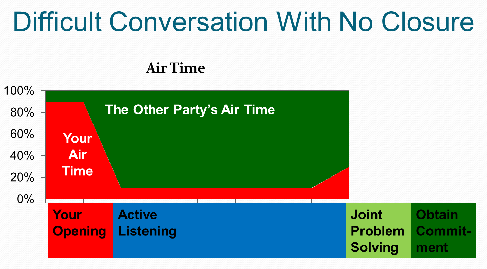

Let’s be realistic. Some difficult conversations do not end with a solution. The other person may be too stubborn. If you do your part well, but the other person resists your efforts, your difficult conversation may turn out like this.  This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

This is not necessarily a bad outcome. For many, being confronted with a shortcoming is shameful.

I had a difficult conversation with an intern that started: “Dolly, your work has been slipping recently. Several people have reported smelling alcohol on your breath. I am concerned about your reputation. I am reluctant to assign you to important projects or have you go to meetings without me.” Dolly never admitted to a drinking problem. She did not agree to seek help. Yet, the issue disappeared overnight. When her internship ended months later, I gave her high performance ratings and a stellar recommendation.

If the other person has difficulty admitting a personal failing, there can still be change, but it will follow a different pattern. The individual you confront may go back to their office and think about what you said. Sometimes, that triggers the change you seek. They may never admit you were right or confess their shortcoming. That’s OK. You can live with the change even if you don’t get the apology.

The worst case is that change does not happen. Let’s acknowledge that we are dealing with adults. You can’t make the other person bend to your will. Give it your best shot – hold the most effective difficult conversation you can – but accept that they must decide whether to address your concerns. If they do not change, you can make other moves. You can set boundaries, end the relationship or get others involved in resolving the situation. Your key responsibility is to have the best difficult conversation you can without pretending you can control the other person’s reaction.

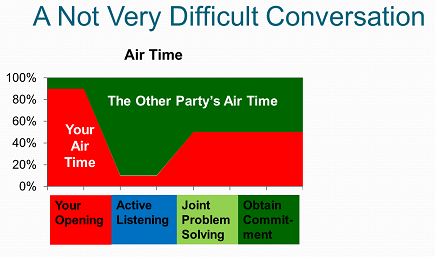

I have coached many clients on how to hold a difficult conversation. We work together to craft a powerful opening. We practice listening. We practice managing emotions. We even role play the difficult conversation. And then, my client goes off to hold the conversation. Surprisingly often, my client is surprised because the conversation turns out to be not very difficult at all.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

Most adults like to be treated like adults. When your difficult conversation begins well, your appropriately assertive statement can quickly lead to a heartfelt apology and a sincere commitment to do things differently. That’s intelligent change at its best. Prepare well. Expect difficulty and you may be pleasantly surprised.

My thanks to executive coach Art Gingold for refining my thinking on difficult conversations.

Pingback: Two Steps to Active Listening

Pingback: Practicing Leadership Skills in Safety